Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

Science Fiction allows you to picture a future which is unimaginable today. Not coincidently, many of the great innovators and inventors were science fiction devotees, as you can see from modern devices.

The iPad and iPhone? Go back to the Starship Enterprise and check out the devices Scotty and Spock were using. The iWatch? Dick Tracy got his smartwatch 70 years ago in 1946. The space race we see between Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson can be traced to being inspired to “boldly go where no man has ever gone before”.

The movie “Her” was an interesting cocktail that combined science fiction, romance, and comedy and received an Oscar for “Best Original Screenplay” in 2014. Situated in a futuristic LA, Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) rebounding from a pending divorce from his high school sweetheart, purchases a talking and personal operating system with artificial intelligence named Samantha (Scarlet Johansson). Theodore is fascinated by how Samantha is constantly learning and adapting and develops a romantic relationship with “her”.

The story takes many interesting turns, none more mind-opening than when Theodore asks Samantha if she is simultaneously talking to anyone else during their conversation. He is bot-betrayed when she confirms that she is interacting with thousands of people and that she has fallen in love with hundreds of them.

Crazy? Maybe. Hysterical? For sure. Here already? We’re closer than you think. And as we combine Artificial Intelligence with advanced robotics, science fiction is quickly becoming science reality.

STATE OF PLAY

Until recently, large-scale robotics development and manufacturing has been limited to a small group of industrial conglomerates in the United States, Japan and Germany. In fact, six of the ten largest robot producers are over 100-years old.

Source: Yahoo Finance, GSV Asset Management

*Lockheed Aircraft Co, and Glen L. Martin Co. each founded in 1912, merged in 1995; ASEA (est.1883) and Brown, Boveri & Ice (est. 1891) merged in 1988 to form ABB; Northrop Corp. (est. 1939) purchased Grumman Corp. (est. 1930) in 1994; Rockwell International acquired Allen Bradley Co. (est. 1903) in 1985 to form the predecessor to Rockwell Automation

In recent years, however, the fundamentals of the robotics industry have evolved dramatically, sparking a wave of innovation and new market participants. Three key catalysts are driving this trend: 1) Declining market entry costs and the rise of “Smart Robotics,” 2) Accelerating Venture Capital activity, and; 3) Massive bets by leading global technology companies.

The Age of “Smart Robotics”

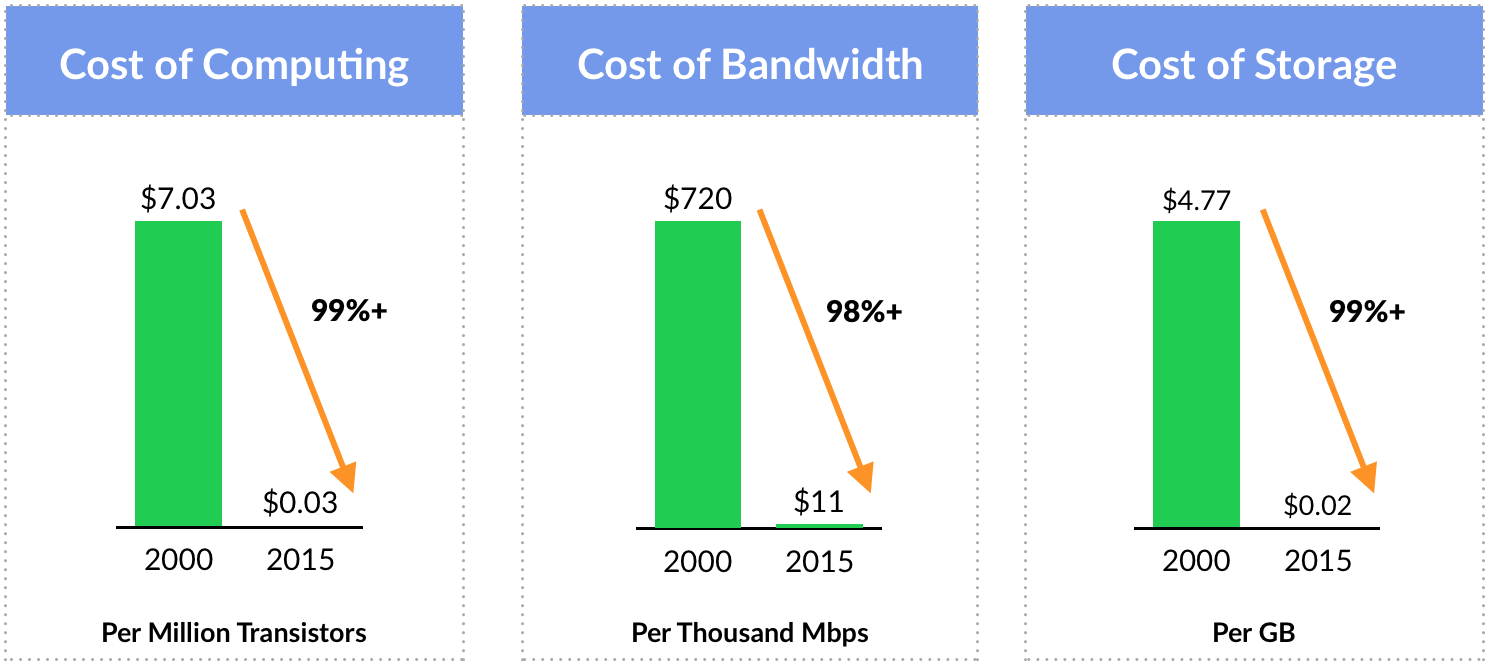

From 2000 to 2015, computing power increased over 100x, while the cost of computing and storage fell more than 99%. During the same period, the price of bandwidth decreased over 98%, and smartphones — which didn’t exist until 2006 — went from zero to over 2.6 billion subscribers, as Moore’s Law continued to cram down component costs.

New technology fundamentals have translated into dramatically lower barriers to entry for robotics startups. But it also means that entrepreneurs are applying emerging technologies to expand and reimagine robot capabilities.

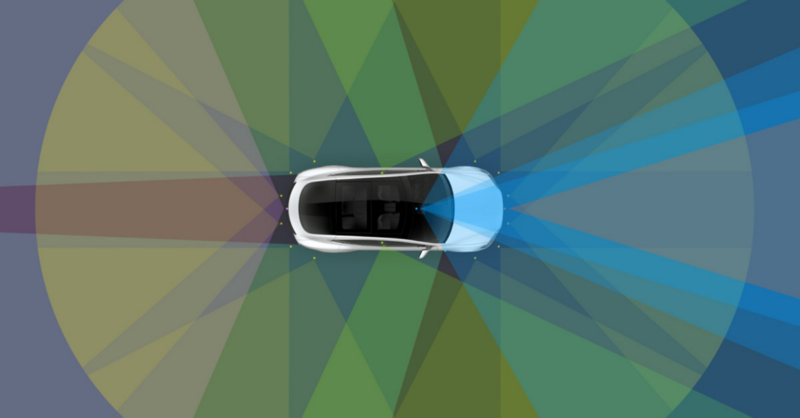

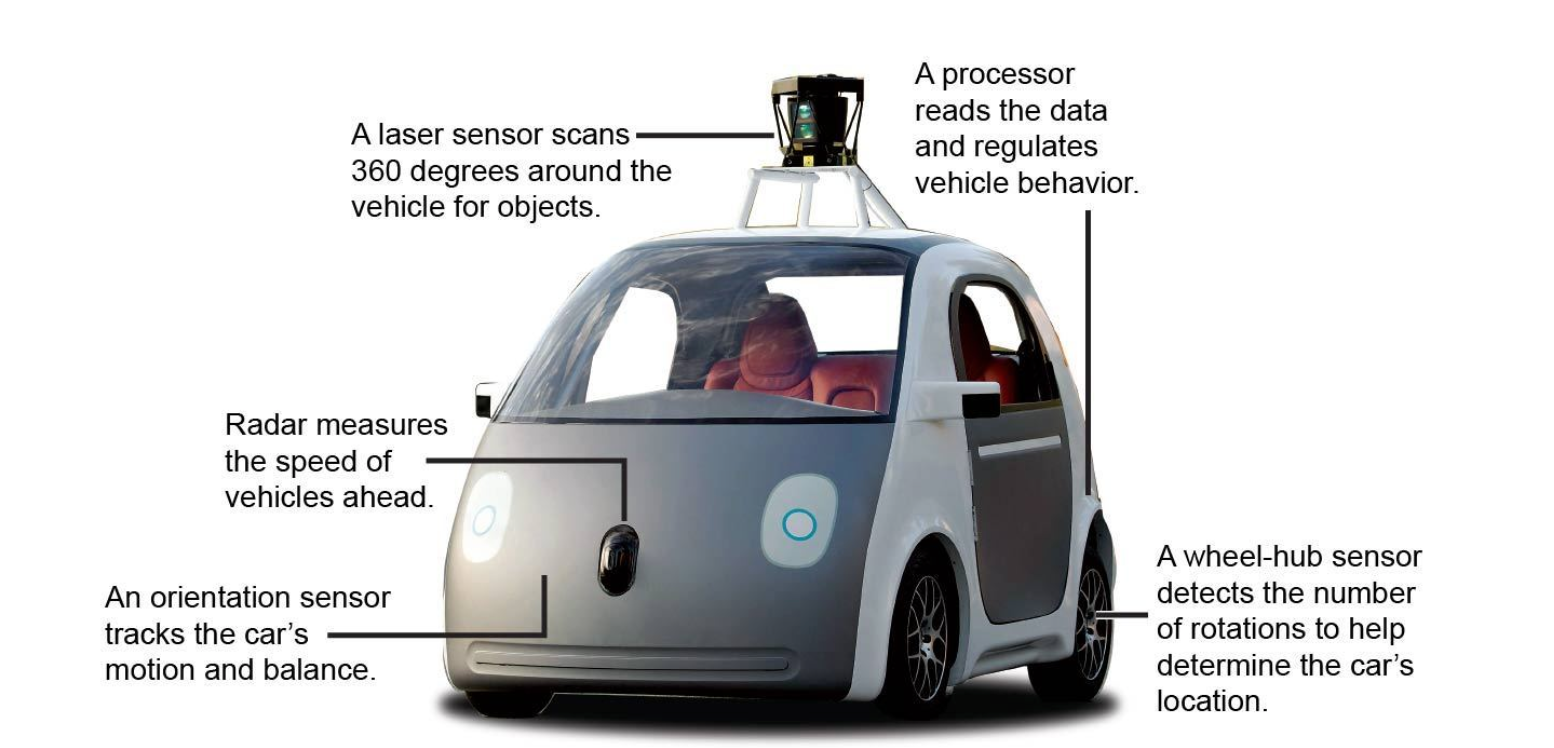

Self-driving cars are a prime example. They couple location information from fixed sensors with maps of the world to navigate. Programs processing optical data then generate instructions for the car’s motor and steering systems. Most importantly, applying advanced Artificial Intelligence approaches like Deep Learning enables self-driving cars to “learn” from their surroundings.

Deep Learning is a process where computers “teach” themselves concepts and tasks by crunching large sets of data. It’s a way of getting computers to know things when they see them by producing rules that programmers cannot specify. For example, Facebook’s facial recognition algorithm, Deep Face — which can recognize human faces with 97% accuracy — was created by feeding computers with millions of images of faces. The same principle can be applied to teach a car what a “Stop” sign is, or how to merge onto a highway.

In the Old World, robots were deployed to complete precise, repetitive work, in carefully designed settings like an assembly line. Adaptability was neither a capability nor a priority. That’s all about to change.

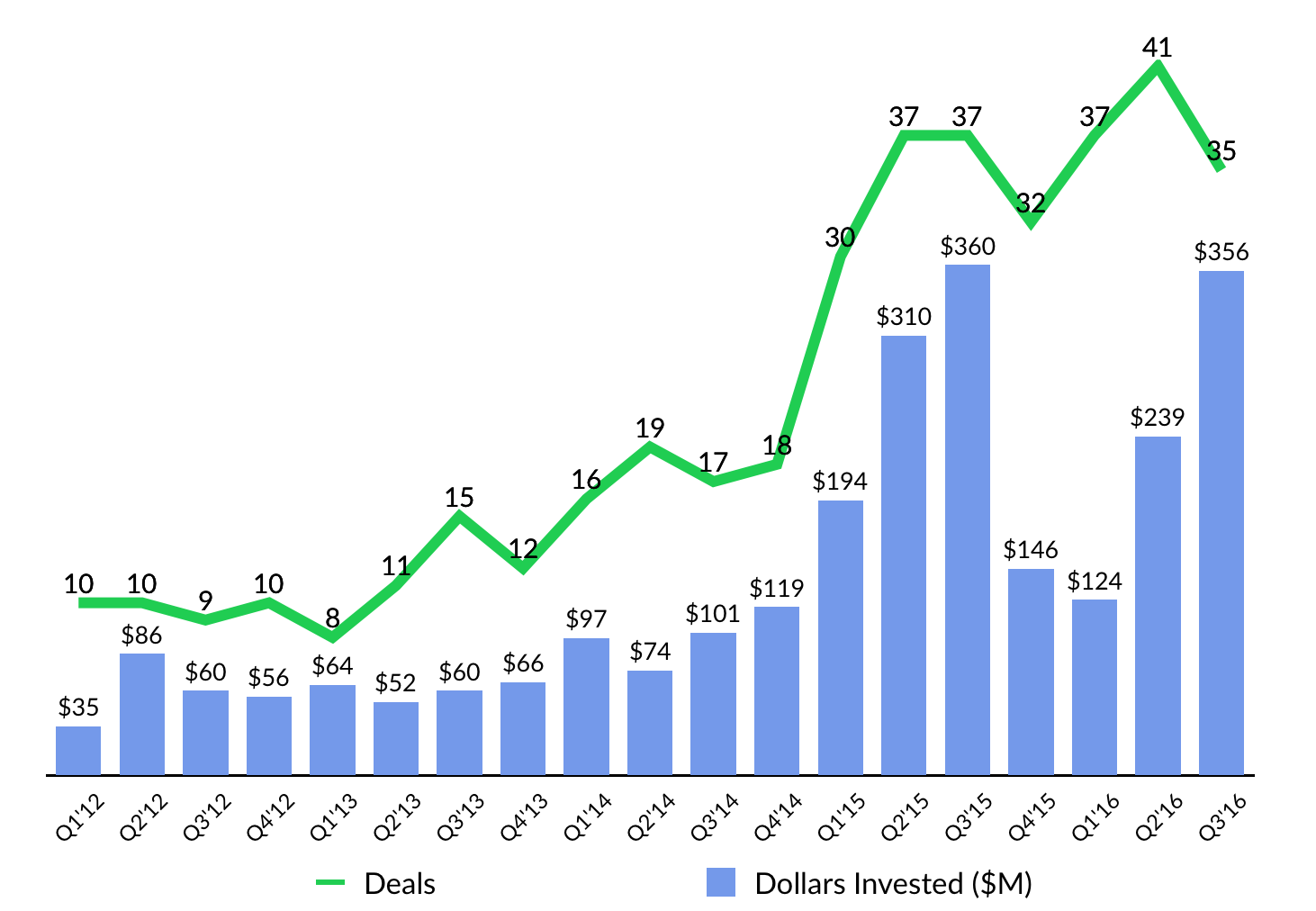

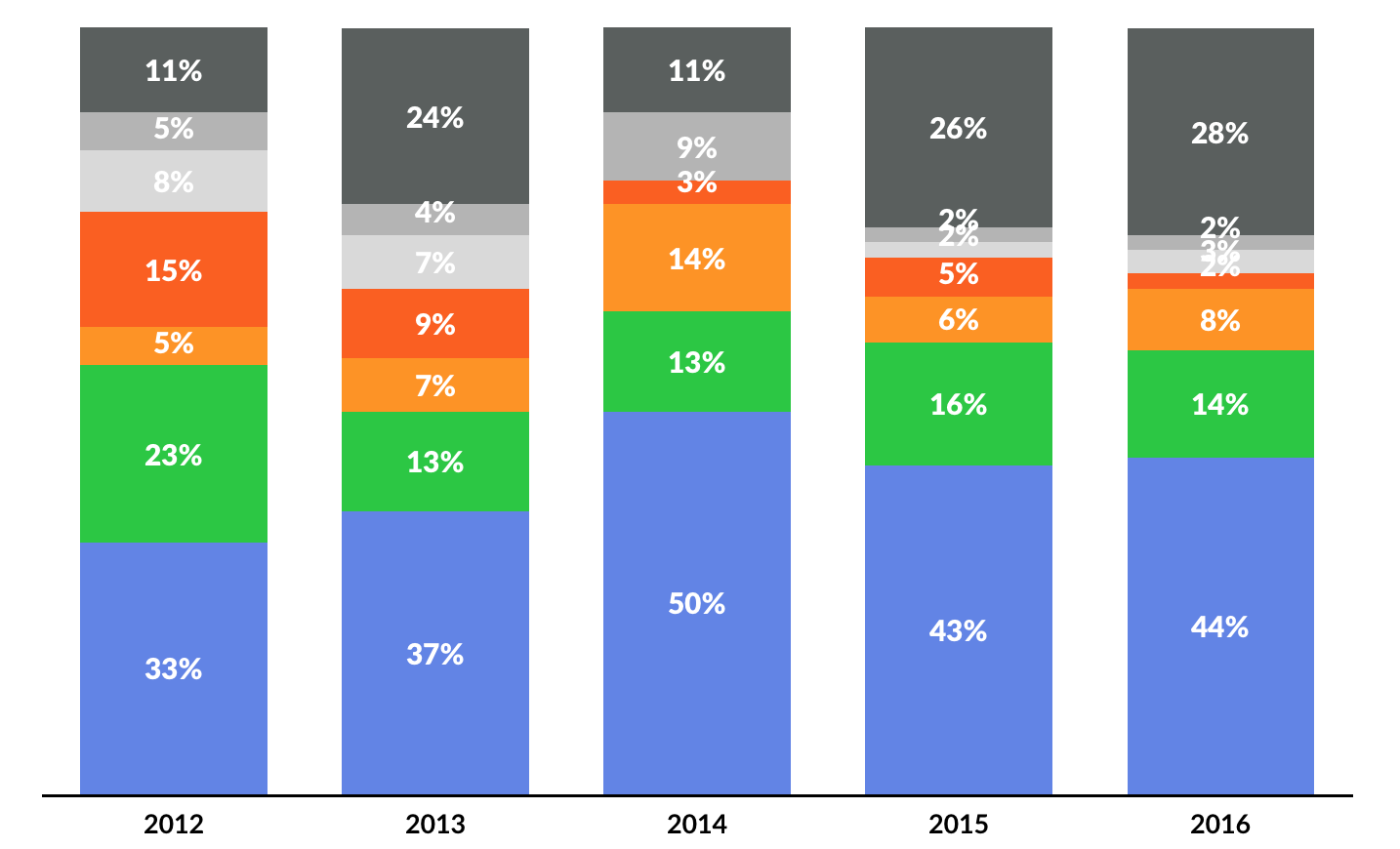

VC Investment Activity

According to CB Insights, since 2012, Venture Capital firms have deployed $2.6 billion to robotics startups across 405 deals. With increased entrepreneurial activity and the rise of “Smart Robotics, ” deals grew from 70 in 2014 to 174 in 2016. Early stage financings still dominate the action, with nearly 60% of deals in 2016 being done in the Seed or Series A rounds.

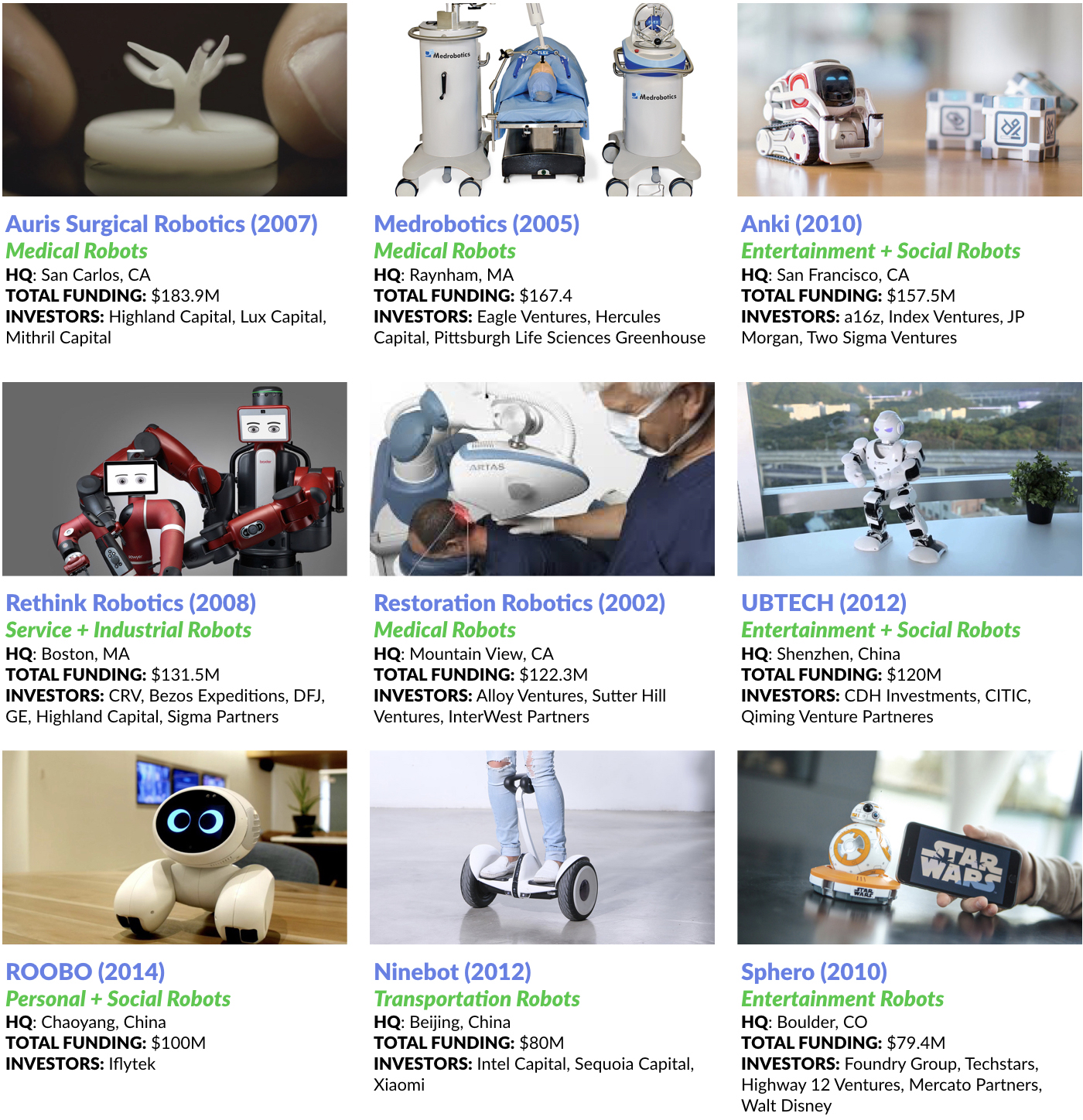

Notable 2016 financings included Anki, an entertainment robotics company, which raised $53 million in June from a syndicate of leading VCs, including Andreessen Horowitz and Index Ventures. Anki’s products include Overdrive, a battle racing system, and Cozmo, a surprisingly “emotional” robot companion. Both are powered by Artificial Intelligence.

China’s ROOBO raised $100 million in September 2016 to build out a suite of personal robots that include Pudding, a voice-controlled, educational robot for kids, as well as Dogmy, a robo “pet.”

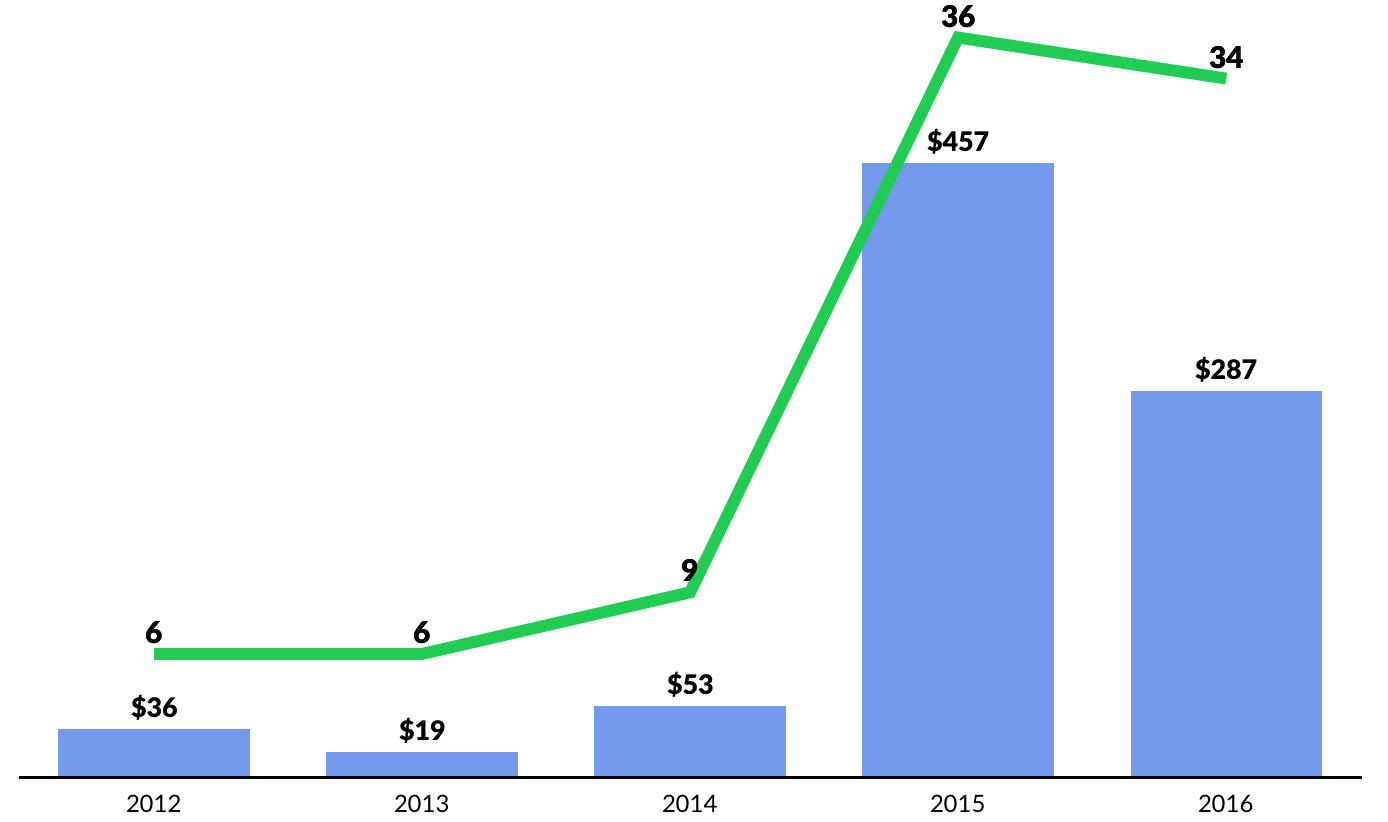

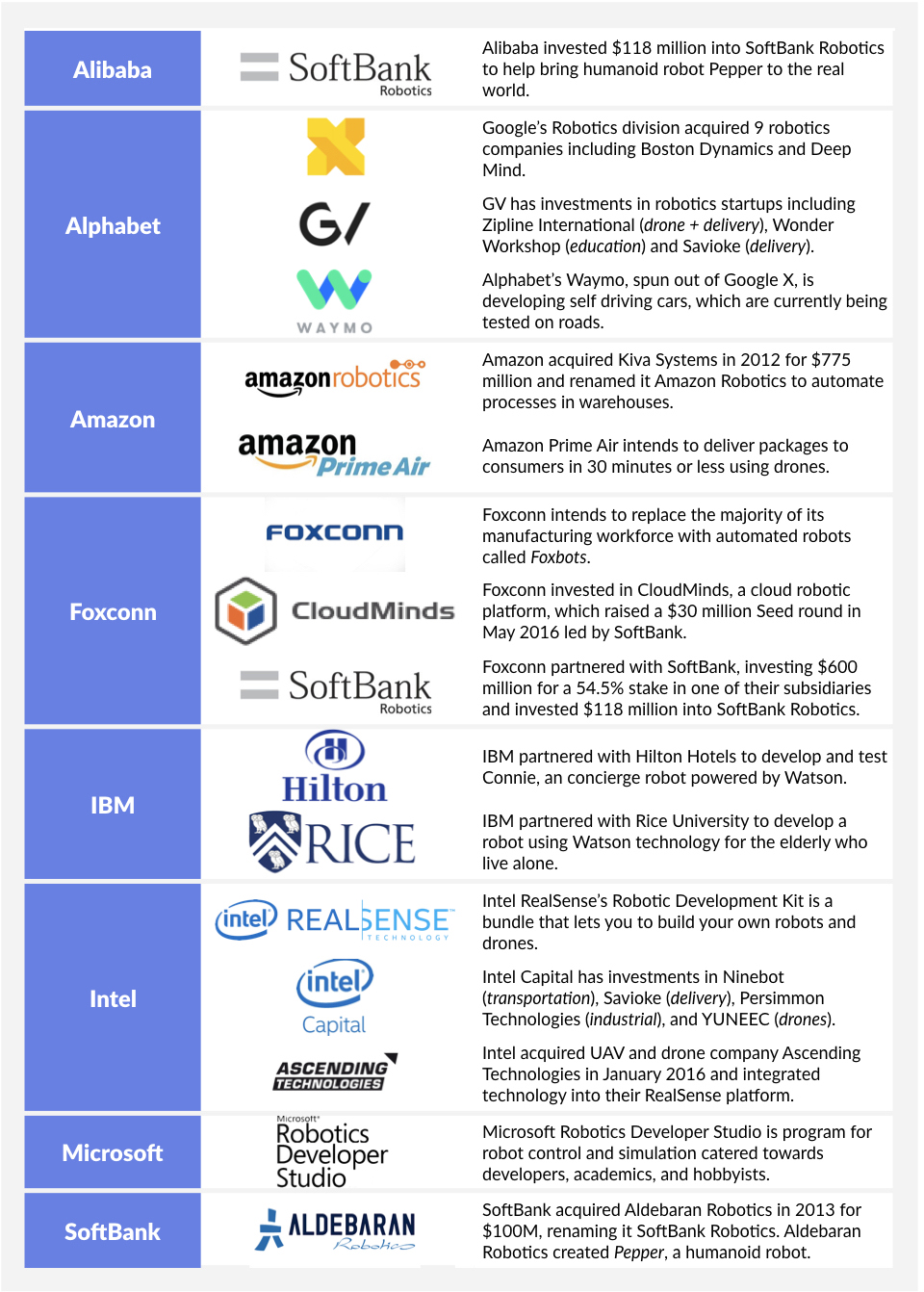

Corporate Investment Activity

Leading technology companies, including Alphabet (Google), Intel, Foxconn, Qualcomm and GE, have also aggressively moved into robotics, investing over $740 million across 70 deals in 2015 and 2016 alone.

In just over a year, Alphabet kickstarted the creation of a robotics innovation arm, acquiring eight promising robotics startups beginning in 2013. While the company has kept its plans close to the vest, the new technologies could be applied to everything from self-driving cars, to a much broader array of autonomous systems — including warehouse work, package delivery, and even elderly care.

With its acquisition of Kiva Systems in 2012 for $775 million, Amazon kickstarted the creation of a a fleet of warehouse robots that will augment, and eventually phase out the need for manual labor. Rebranded to Amazon Robotics, the subsidiary currently automates fulfillment center operations and has a dedicated focus on robotics research and development. At the end of 2014, Amazon employed 15,000 Kiva bots. Today, it’s over 45,000.

ROBOTICS: KEY INDUSTRIES & APPLICATIONS

Industrial & Manufacturing

Manufacturers like GM have integrated robots into assembly lines since the 1960s when the automaker installed a hulking 4,000-pound arm called the “Unimate” to attach die castings to car doors. Today, a new generation of startups is applying advanced robotics to automate a broad range of nuanced physical processes.

While Amazon’s Kiva robots buzz around busy warehouses, Lowe’s is bringing inventory management robots developed by Bossa Nova Robotics to their store aisles. Bossa bots uses computer vision to scan barcodes and track inventory, generating alerts as supplies dwindle. Additionally, the robots create a digital map of the store, recording the location of each product to help employees keep track of where each item is located.

In May 2016, Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Foxconn announced that it replaced 60,000 factory workers with the introduction of various manufacturing and warehouse robots. The company already produces 10,000 “Foxbots” annually and intends to aggressively automate its sprawling workforce moving forward. It is estimated that Foxconn employees over one million workers in China alone.

In this context, “China” is the key megatrend in industrial and manufacturing robotics. To date, the World’s largest producer of everything from clothes to electronics, has depended on low-cost, low-skill labor. But as economic growth slows and wages continue to rise, the Chinese government is eager to see its workforce diversify and its manufacturing industries become more technologically advanced.

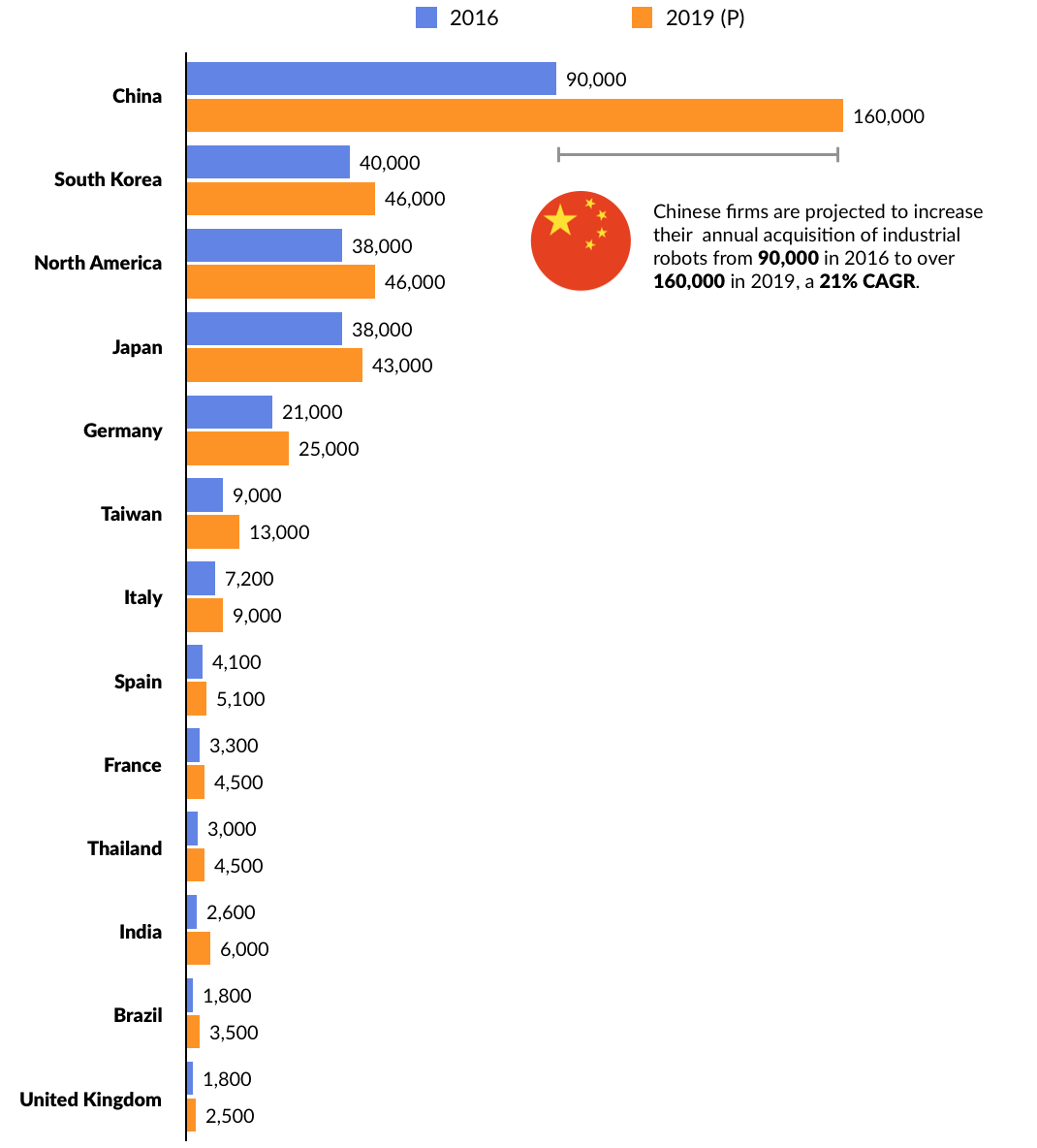

Accordingly, China has embarked on an audacious effort to fill its factories with advanced manufacturing robots. In 2016, the country acquired an estimated 90,000 industrial robots, more than the next two largest robot adopters combined — South Korea (40,000, and the United States (38,000).

China robot acquisitions are projected to explode to 160,000 by 2019. The province of Guangdong alone — the nerve center of Chinese manufacturing — has already committed to invest $154 billion in robot installations.

Transportation + Delivery

In 2004, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched a Grand Challenge series, a multimillion-dollar competition for university robotics teams to design autonomous vehicles. A rivalry quickly developed between Stanford and Carnegie Mellon (the schools traded the top spots in the first two years of the competition) that shaped the early future of self-driving cars.

Sebastian Thrun, the leader of Stanford’s winning team, took a leave from the university in 2007 to work on Google Street View, and later founded the company’s self-driving-car project. It became a starting gun for the entire industry. As opposed to focusing on assisted driving, the company instead committed to creating a car without a steering wheel or pedals. It was the stuff of science fiction and it captured the World’s imagination. (Click HERE to read “Born to Run,” GSV’s latest research on the future of transportation and mobility.)

While robots on wheels are taking to the highways, flying robots, or Drones, are lifting off faster than most predicted. In 2010, the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) estimated that by 2020, there would be 15,000 consumer drones in the country. Today, that’s fewer than the number of drones sold per month. The Consumer Electronics Association (CEA) estimates that over three million drones were purchased in 2016.

Today, the global drone market is estimated to be worth $8 billion, growing to over $11.5 billion by 2020. Consumer drone spending is projected to grow at a steady 10% CAGR for the next five years, from $1.6 billion today to $2.6 billion. (Click HERE to read “Eye in the Sky,” GSV’s latest research on the future of Drones.)

Looking forward, the most compelling category is just beginning to emerge. Commercial drone services were estimated to be less than $100 million in 2015. But the market is growing at a 43% CAGR — expected to top $500 million in 2020 — and will accelerate faster still as drone technology and regulations evolve.

A key industry that will be transformed by driving and flying robots is delivery and logistics.

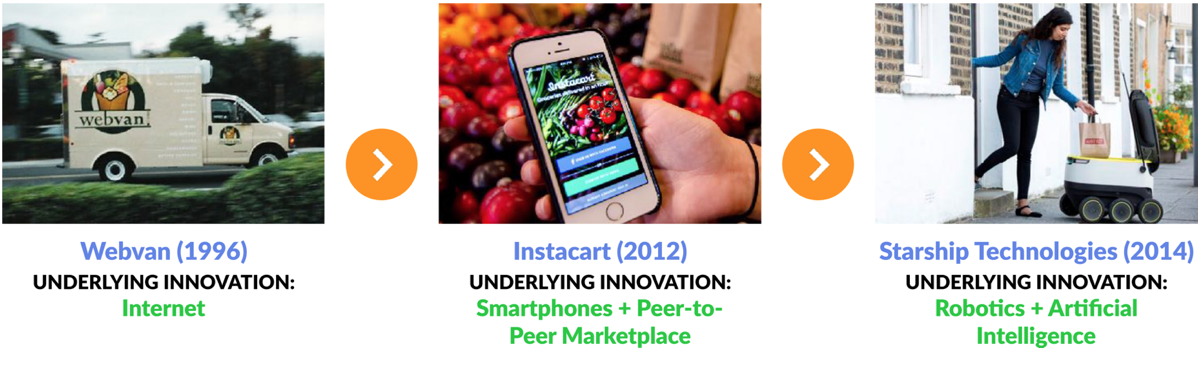

We’ve heard this promise before. In the dot-com bust, on-demand delivery services like Kozmo, Urbanfetch, and Webvan became a symbol of the excess that fueled the crash. The idea then was that the Internet would create efficiencies that offset logistical costs. At its peak (or valley, depending on your perspective), Kozmo was charging $2 per delivery while hemorrhaging money on courier and warehouse expenses (in 1999, Kozmo reported $3.5 million of revenue on $29 million of expenses).

Beginning in 2013, a new crop of on-demand delivery businesses emerged with an eerily similar value proposition, from Instacart ($675M raised) to Postmates ($278M raised), Deliveroo ($475M raised), Delivery Hero ($1.3B raised) and China’s Ele.me ($2.3B raised). As private financings surged, Benchmark-backed GrubHub recorded a successful IPO in 2014 and is valued at nearly $3 billion today.

The key different is that in 2000, there were only 370 million people on the Internet (roughly 5% of the world’s population), smartphones were a fantasy, and applications off of a platform had not been invented.

Today, digital infrastructure is in place, with three billion people on the Internet, over 2.6 billion smartphones in the hands of Digital Natives, and 226 billion apps having been downloaded from Apple and Alphabet (Google). Goods, services, and delivery teams can be more efficiently networked and coordinated. Peer-to-peer marketplaces that quickly network available labor (think Uber and Lyft), means that part-time delivery armies have been assembled rapidly and cost-effectively.

Robo deliveries, which eliminate human labor costs, are the next phase. Starship Technologies, for example, conducts door-to-door deliveries with six-wheeled container robots that now operate in 56 cities across 16 countries. Starship’s delivery bots have travelled over 10,000 miles. The company recently partnered with Postmates and DoorDash to fulfill orders, with tests underway in Redwood City, CA and Washington D.C. In January, Starship completed a $17 million Series A financing led by Shasta Ventures.

At the other end of the market, large e-commerce platforms are testing regulatory boundaries as they aim to deploy fleets of drones to complete deliveries. In December 2016, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announced that the company had completed its first fully-autonomous drone delivery in the sleep countryside town of Cambridgeshire, England. A customer ordered an Amazon Fire streaming device and a bag of popcorn and found the goods at his doorstep 13 minutes later.

In China, online retailer JD.com started the trial of a drone delivery program in late 2016, serving rural locations outside of Beijing, as well as Jiangsu, Shaanxi and Sichuan provinces. The list goes on.

Services + “Social”

The first generation of service robots were designed assist people with repetitive tasks like housecleaning. In 2002, iRobot created the most popular service robot to date, the Roomba vacuum cleaner, which has sold over 15 million units to date. Since then, service robots have been created to automate a variety of tasks — from monitoring homes and malls, to preparing food and sorting trash.

Earlier this month, Cobalt, founded by former Google X and SpaceX engineers, introduced an indoor security robot focused on anomaly detection — from human activity to doors, windows, and suspicious objects. Cobalt’s robots are powered by the same technology packed into autonomous vehicles. Investors include Bloomberg Beta, Promus Ventures and Comet Labs.

Momentum Machines, founded in 2009 by a group of engineers form Stanford, Tesla, and NASA, have created a robot chef that can make gourmet hamburgers from scratch with no human intervention. Robot bartenders, such as those made by Monsieur, are already being piloted in sports arenas, hotels and movie theaters.

We’re also seeing an increased emphasis on the personalization of robots, with companies making consumer products that are meant to be social companions. Founded in 2010 by a team from Carnegie Mellon, Anki builds entertainment robots that combines the aesthetic of Pixar’s WALL-E with the functionality of Disney’s Baymax.

Its Cozmo product, for example, is a toy robot with built-in facial recognition that is able to develop skills over time through play and use. But what’s special about Cozmo is its emotional adaptability. It responds to human interactions in very human ways, throwing tantrums and flapping around in excitement when appropriate. Anki recently released Cozmo’s SDK, allowing engineers to build programs off its platform, effectively doing for robotics what iOS and Android did for mobile technology.