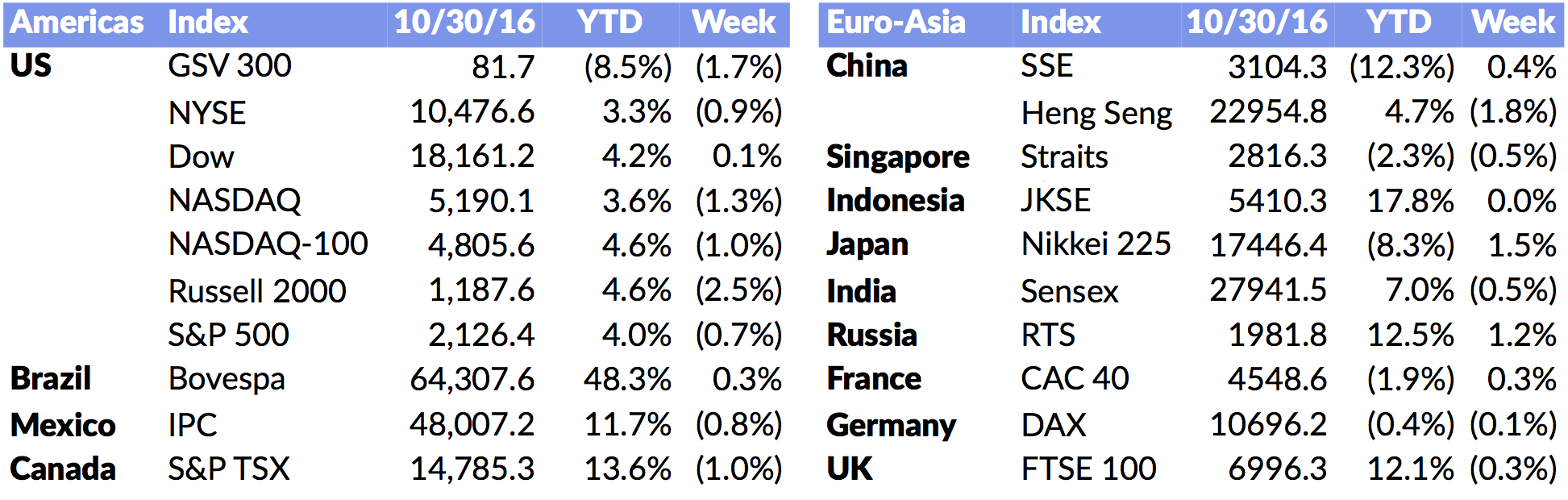

Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

Movement is in our DNA. Until about 10,000 years ago — or 99% of human history — there were few, if any homes or villages. People were nomadic, chasing food and gentler climates.

While we couldn’t change the weather, we learned how to domesticate plants and animals in what is now called the Neolithic Revolution. And when the food stopped moving, so did we.

In the next 10,000 years, historians might look back and name our era the “Metropolis Revolution.”

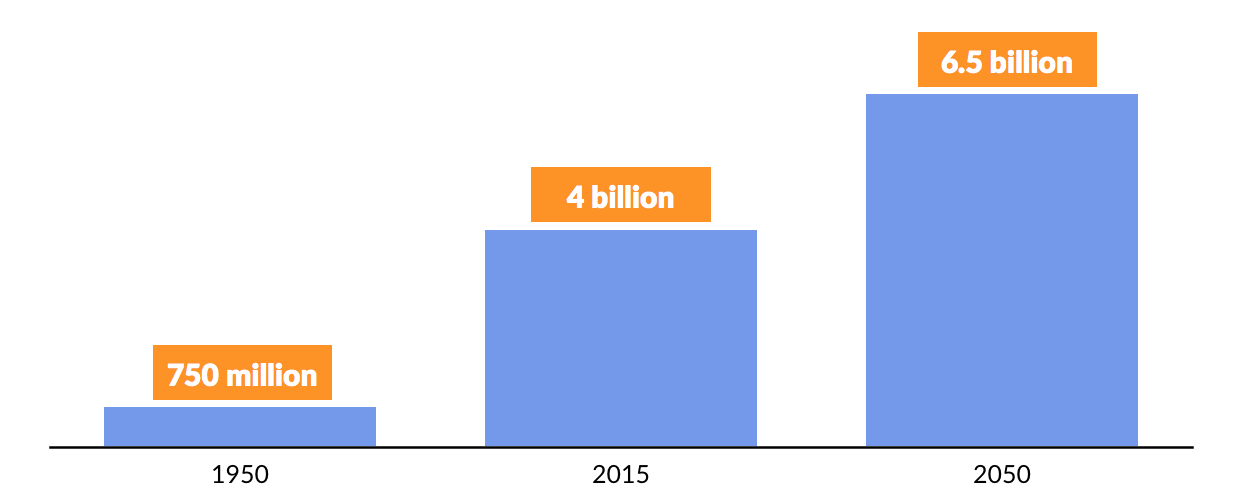

Today, the United Nations estimates that four billion people, or 54% of the World’s population, live in cities. In the next 15 years, the Economist projects that urbanization will increase average city density by 30%. By 2050, the ranks of urban dwellers will swell by 2.5 billion to nearly two-thirds of global population.

If you look at the United States, there are 10 cities with a population of one million or more. In China, there are 160. The official population for Shanghai is 34 million. But demographers will tell you that based on cellphone subscription data, it’s probably over 40 million. That is larger than the entire population of Canada.

While we’re no longer nomads, we still move around. But increasingly, it’s all happening inside of cities. Today, urban travel already accounts for nearly two-thirds of the total distance people cover per year. Based on the current trend line, this will triple by 2050, stretching urban transportation systems to the breaking point.

The traditional solutions to congestion — building more roads and expanding public transportation — are constrained by cost and time. The future of human mobility will be shaped by new models and technologies.

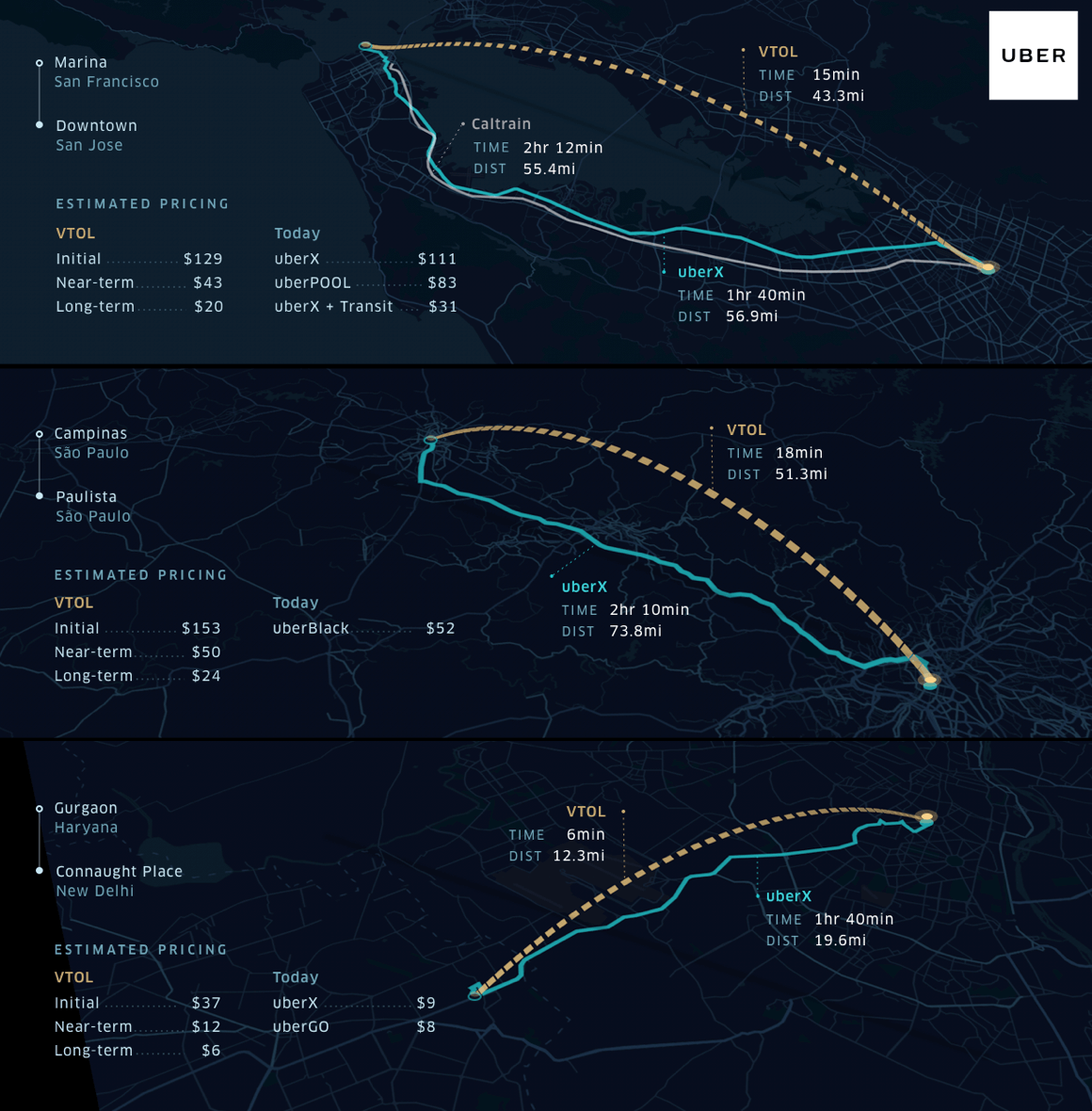

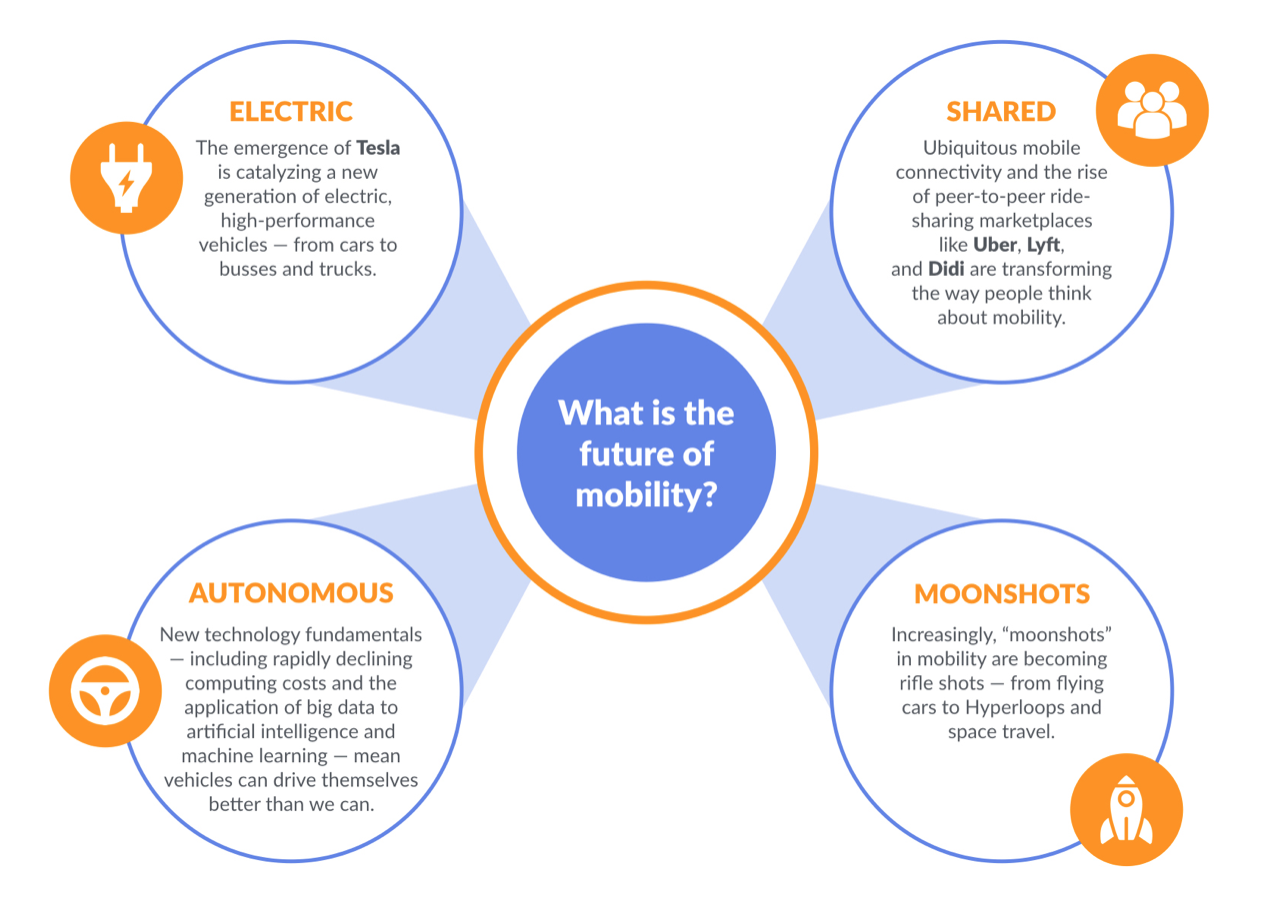

There are three key trends emerging, revolving around a re-imagined automobile — Electric, Shared, and Autonomous. And in a fourth trend, we see “Moonshots” in transportation and mobility becoming “Rifle Shots” — from Hyperloops to on-demand flying taxis.

ELECTRIC

Why does Tesla trade at 17x P/S of General Motors?

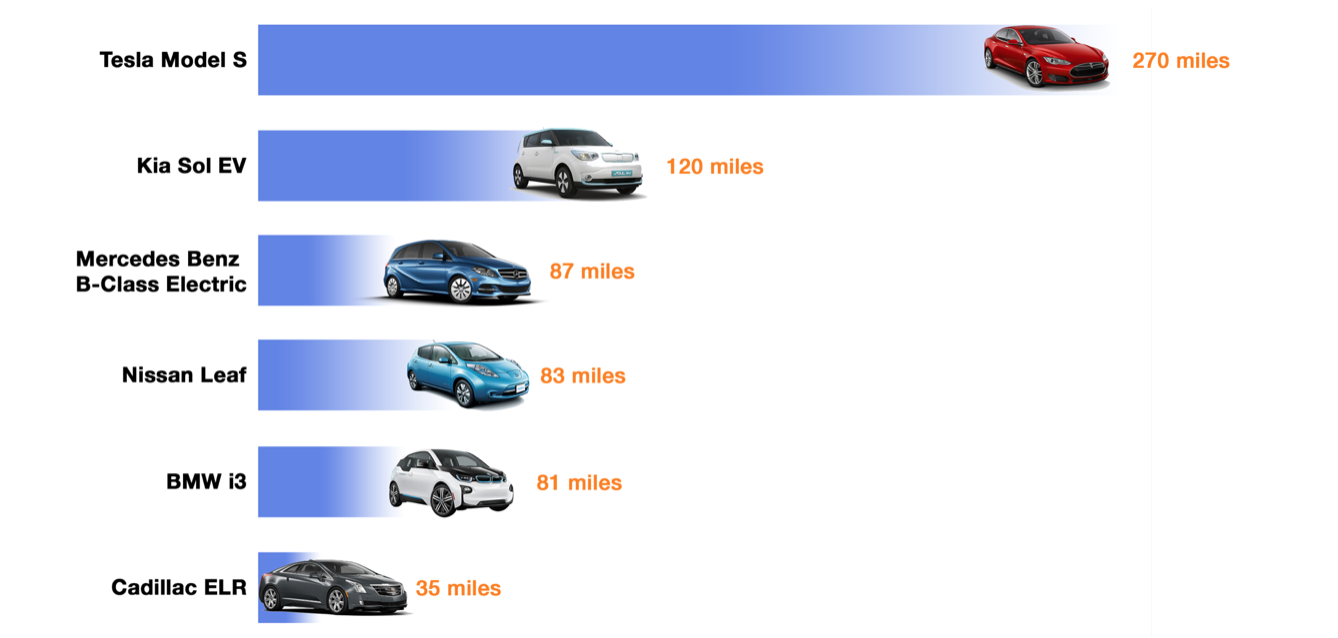

Because a Tesla now gives you the ability to drive 270 miles and you can recharge your car in the time it takes to grab lunch. If Teslas only went 40 miles, the company would be dead in the water. Add in the fact that Teslas are effectively computers on wheels (with hands-free mode they drive themselves) and stylish to boot, and you have a game-changing product.

General Motors, in contrast, spends over $7.2 billion per year on R&D, and the net result has been the Cadillac ELR, which will take you 35 miles on a charge.

Why It Matters

Global electric vehicle (EV) production, catalyzed by the emergence of Tesla, is surging. EV sales rose 60% in 2015, spurred by improved design, falling battery costs, increasing consumer interest, and a favorable regulatory environment.

The timing couldn’t be better. As a corollary to swelling urban centers around the World, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports that the global middle class, which numbered 1.8 billion in 2010, is expected to grow to 4.9 billion by 2030. Defined as households that spend between $10 and $100 per day, this a cohort of commuters and car-buyers that will be more mobile than previous generations.

To achieve global sustainability, we can no longer choose between “green” and growth. We need both. In this context, improving fundamentals in the electric vehicle market point to explosive growth.

While electric vehicles still represent fewer than 1% of total vehicles sold in most markets, the average price of lithium-ion battery packs used in EVs fell 65% from 2010 to 2015 — from $1,000/kWh to $350/kWh. It continues to drop, driven by scale, improvements in battery chemistry and better battery management systems.

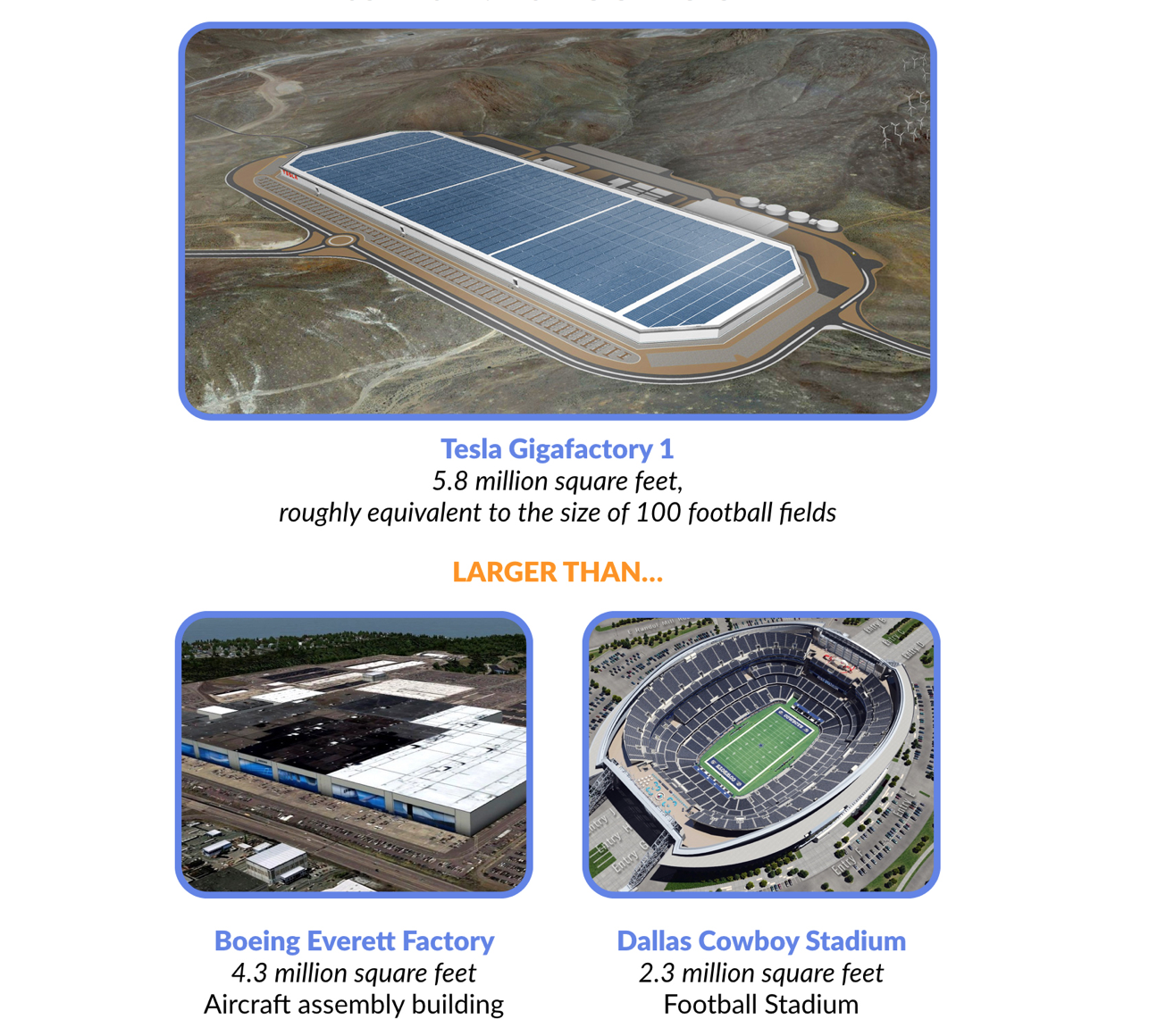

Here again, Tesla is redrawing the frontiers of the possible, investing $1.6 billion to launch a “Gigafactory” in Nevada to produce lithium-ion batteries at scale. The company estimates that the factory will produce 35 gigawatt hours of batteries by 2018. That’s the equivalent to the entire world’s production in 2014.

What’s Next

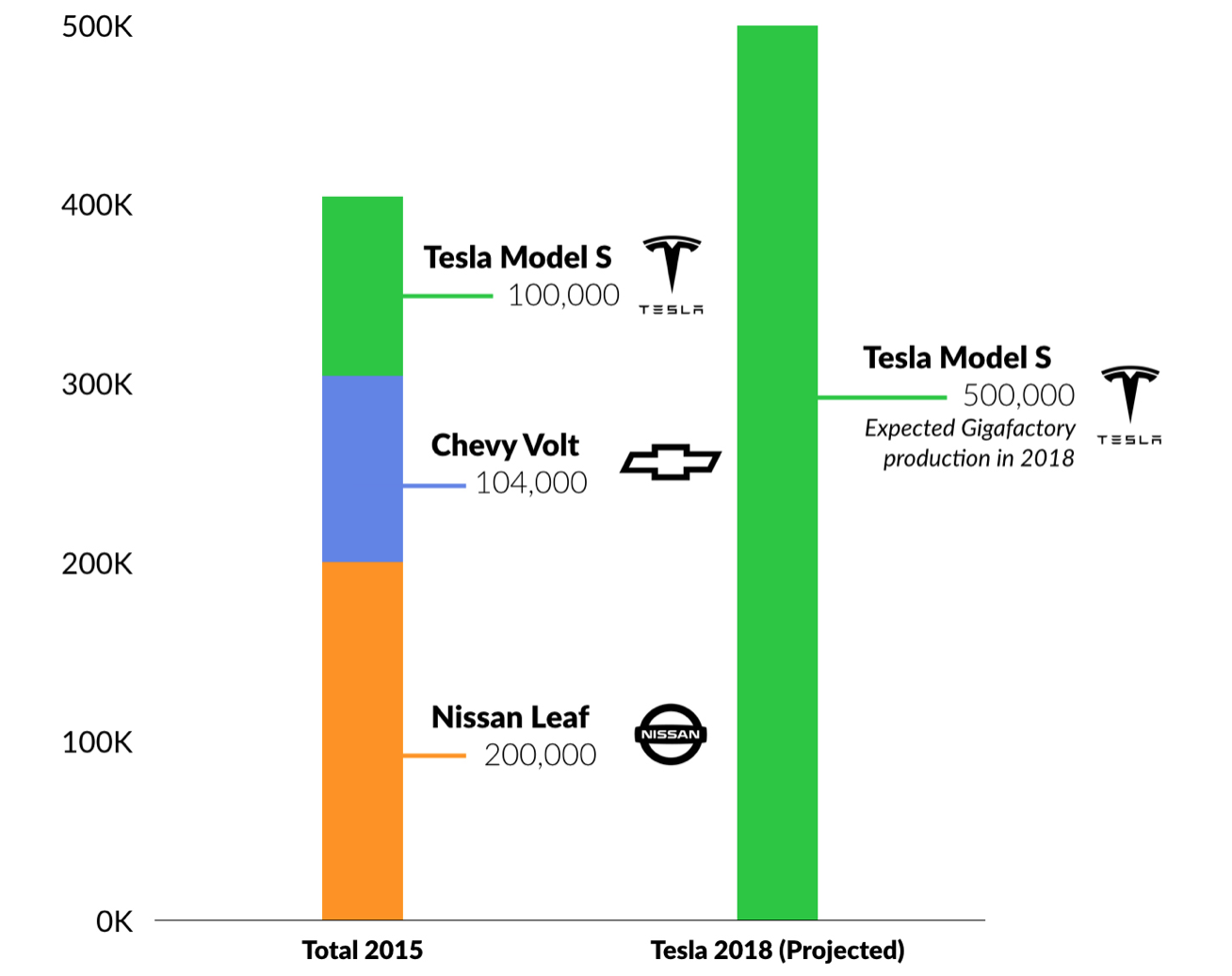

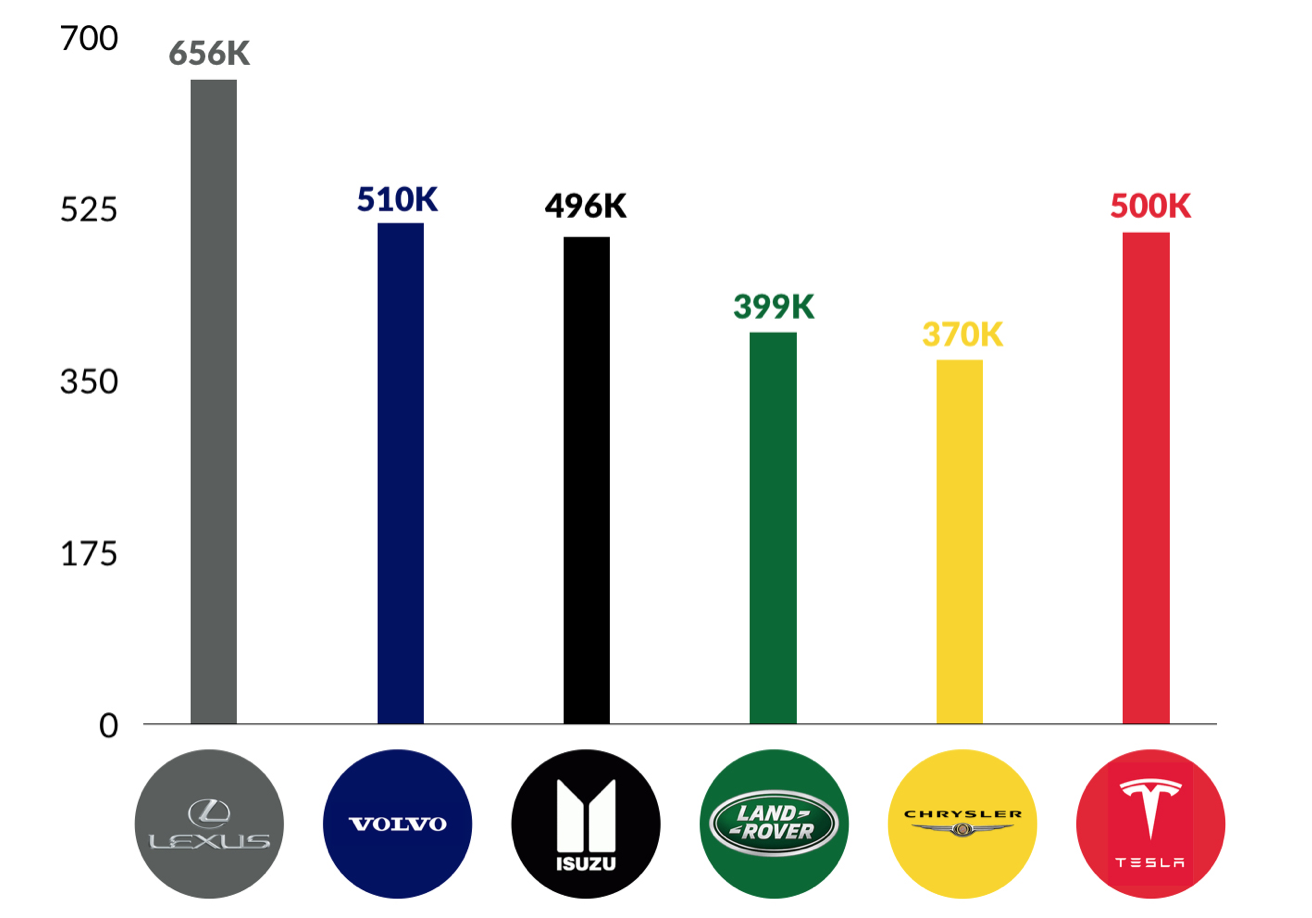

Consumers are taking notice. Tesla aims to sell 500,000 cars in 2018. If it hits the mark, it will be a major milestone for the electric vehicle market. To put that number in perspective, the total sales (all-time) for the three most popular EV models (Leaf, Volt, Model S) add up to an estimated 404,000 cars as of December 2015.

Tesla is still a relatively small auto manufacturer, but if it meets its stated production goals in 2018, it will be comparable with brands like Chrysler, Land Rover, Isuzu, Volvo, and Lexus.

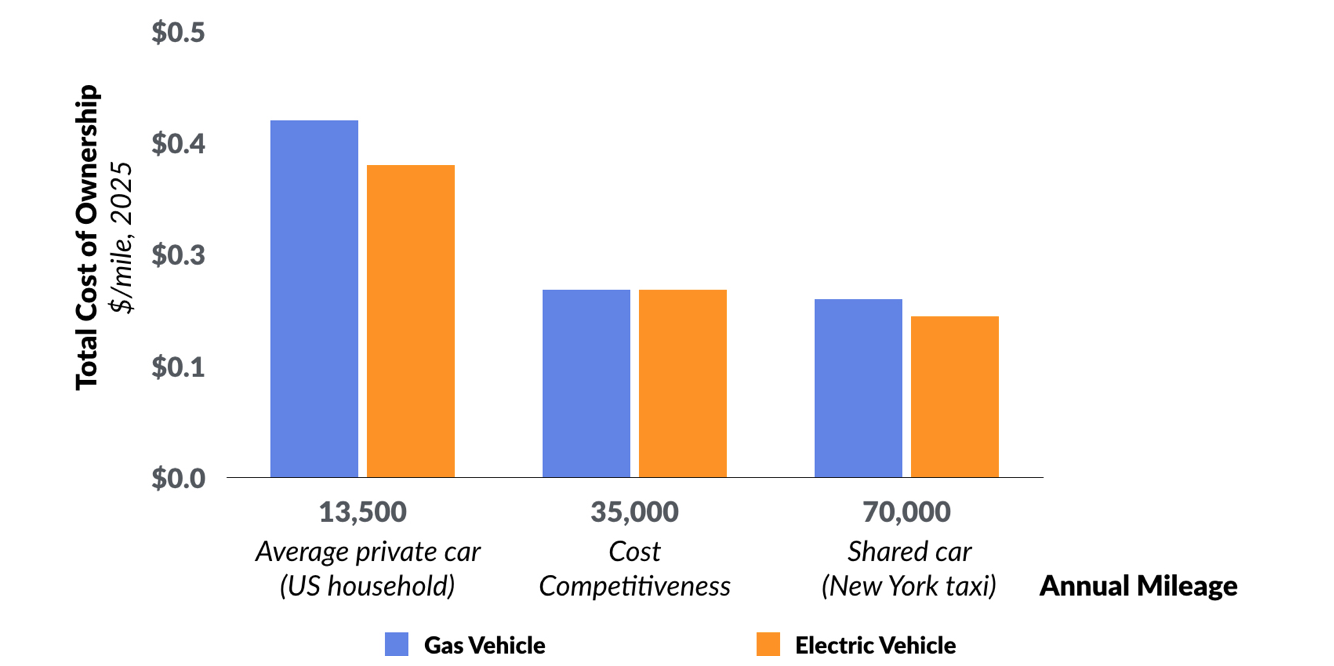

McKinsey estimates that improving technology fundamentals and production at scale will make private EVs competitive with comparable internal combustion engine vehicles by the mid-2020s on a total cost of ownership basis. It will be earlier for high-utilization vehicles, like the cars at work in the ride-sharing networks created by Uber and Lyft. Given their popularity and expanding global reach, these networks are likely to accelerate the adoption and production of electric vehicles.

SHARED

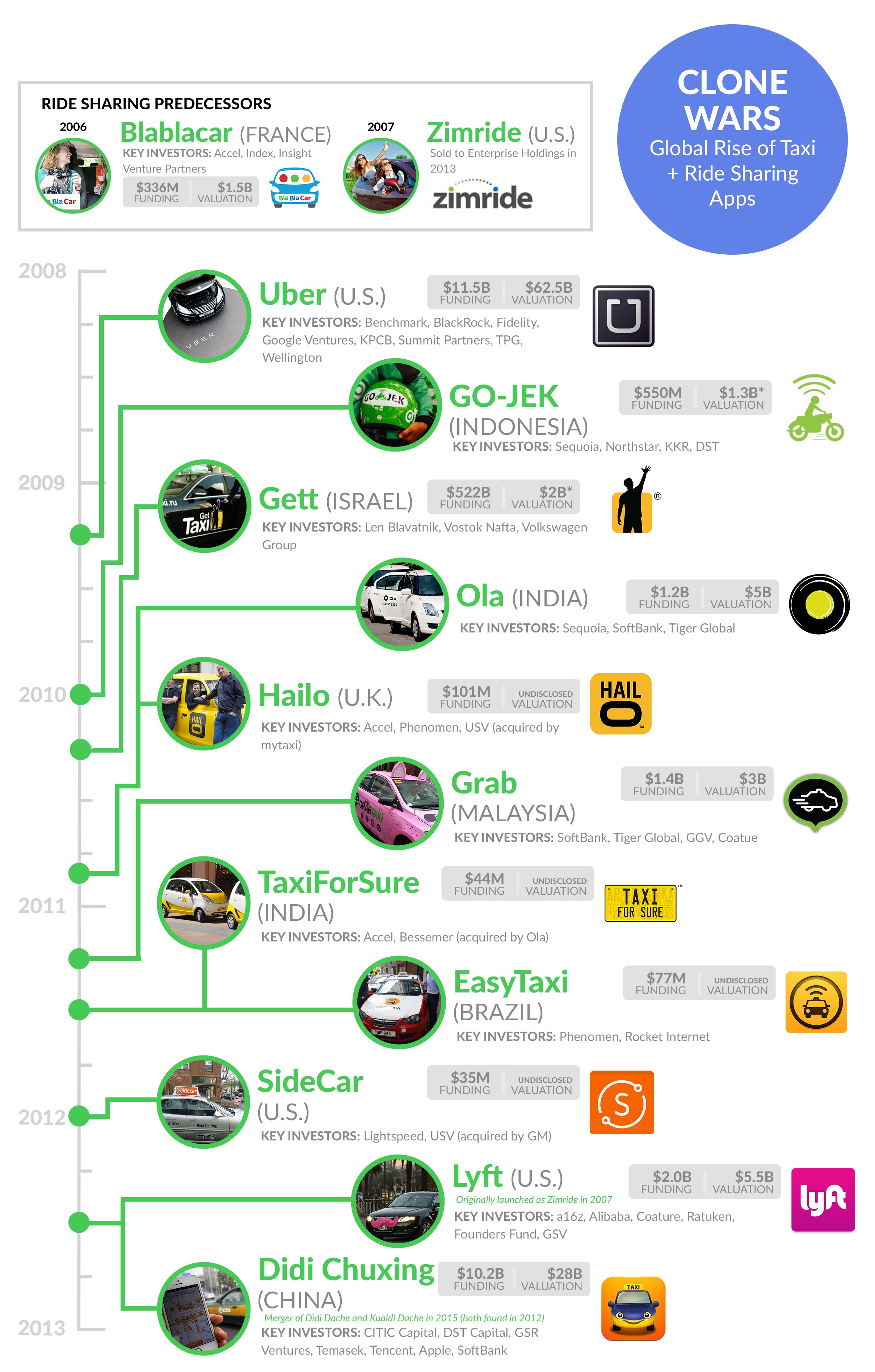

When Logan Green launched Zimride in 2007, no one would have thought that on-demand ride sharing would boom to become a $45 billion industry nine years later. Even five years ago, getting a taxi was a gigantic hassle. In big cities around the World, your best option was — and in many cases still is — literally to “catch” a cab.

Here’s how the model works. You stand on the edge of the street, put your hand up in the air while competing with other would-be riders, and pray for a car to swerve to a stop in front of you. Taxi drivers, meanwhile, troll around blindly for fares, relying on dead reckoning and luck to find passengers.

The ride doesn’t usually go much better. For starters, the customer is never right. Try suggesting a preferred route. And safety isn’t exactly first.

But seemingly over night, a new paradigm emerged. On-demand ride sharing through apps like Uber and Lyft has transformed an erratic experience into a model of efficiency and expedience. And the customer is king. (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Lyft)

So what happened?

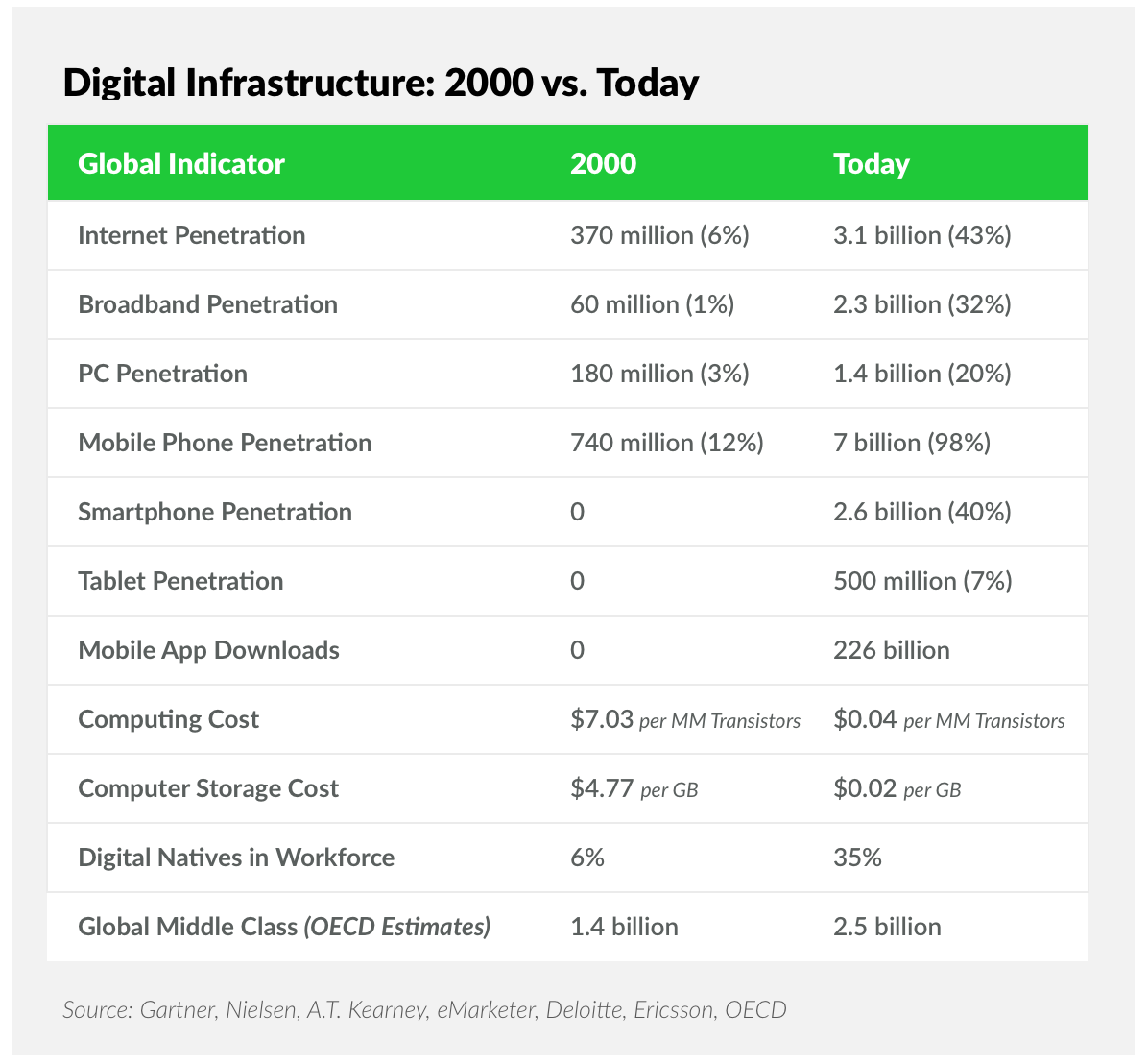

In 2000, there were only 370 million people on the Internet (roughly 5% of the world’s population), no one had heard of a smartphone yet, broadband was a fantasy, and applications off of a platform had not been invented.

Today, digital infrastructure is in place, with three billion people on the Internet, over 2.6 billion smartphones in the hands of Digital Natives, and 226 billion apps having been downloaded from Apple and Google. These dynamics have paved the way for disruptive new businesses to launch at lightening speeds, going from idea to “Billion Dollar Baby” seemingly overnight.

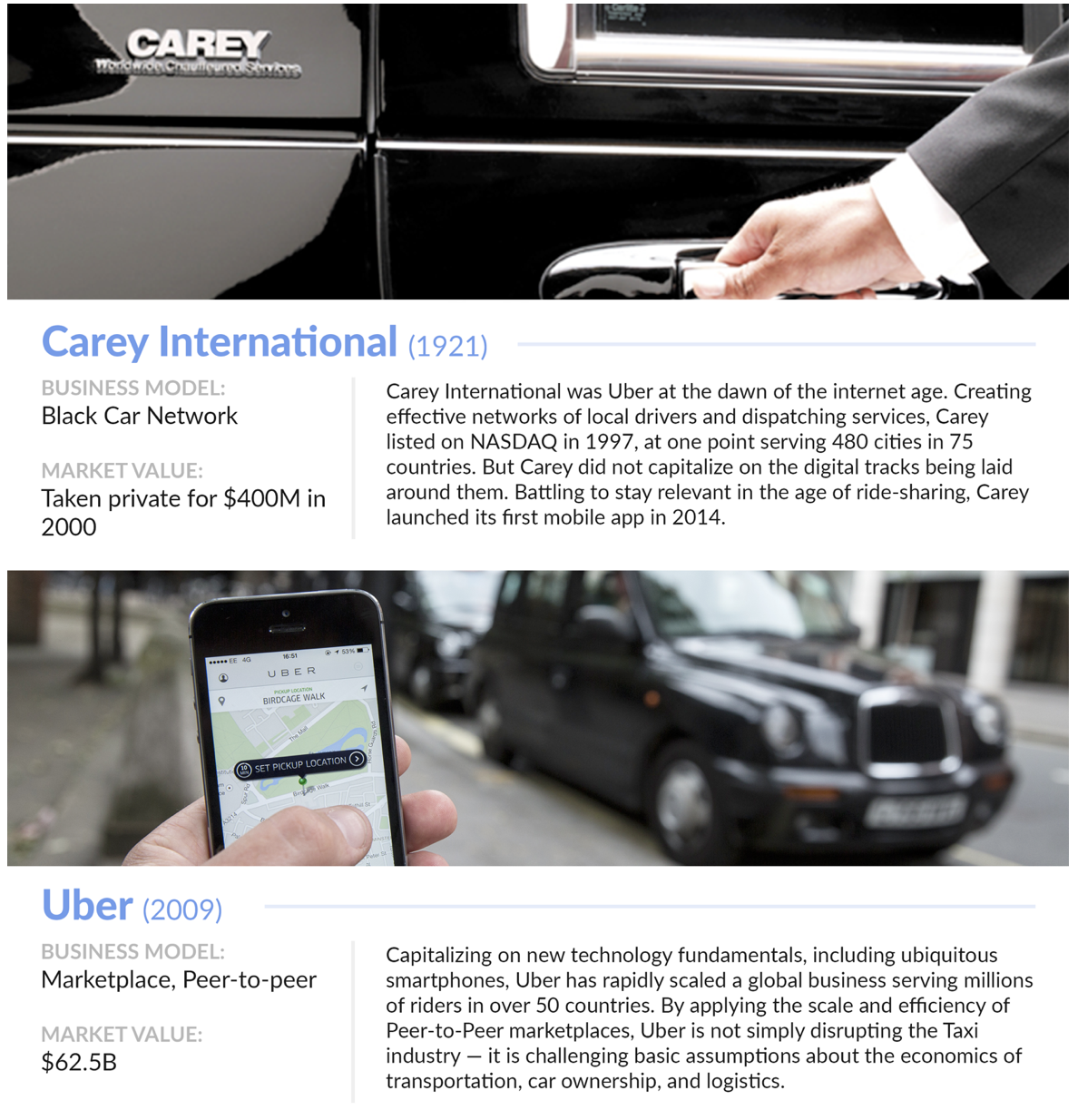

As is too often the case, the “early bird gets the turd.” Carey International was Uber before Travis Kalanick was born. Listed on NASDAQ in what seems like a century ago, Carey created a black car network spanning 1,000 cities around the globe. Effectively it was a brand, an “800” number, and a scheduling service. Sound familiar?

Uber doesn’t own any of the cars in its network. The drivers are independent. Carey should have been Uber, but they lacked the imagination to see the impact that smartphones could have on their business. Carey launched its first app in 2014 — five years after Uber had taken the World by storm.

Why It Matters

Ride-sharing apps are not only easy to use, but they create a variety of efficiencies while empowering the customer. Your ride appears where you want it, when you want it. You don’t need physical money — or even a credit card for that matter — to pay your driver. It’s all in the app.

And a transparent review process ensures that drivers treat their customers well. The better the service, the higher the star rating a driver receives — which in turn translates into a higher likelihood of being connected with riders. Similarly, passengers that consistently demonstrate bad behavior — from no-shows to disorderly conduct — can be removed from a ride sharing platform based on driver feedback.

Given these two fundamental shifts — efficiency and customer experience — it is no wonder that we are seeing a major industry transformations unfold rapidly before of our eyes. We estimate that the industry has grown from $500 million in 2012 to over $45 billion in 2016 — a 208% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR).

While ride-sharing has created a new, superior mobility option for consumers, it is also causing people to rethink automobile ownership.

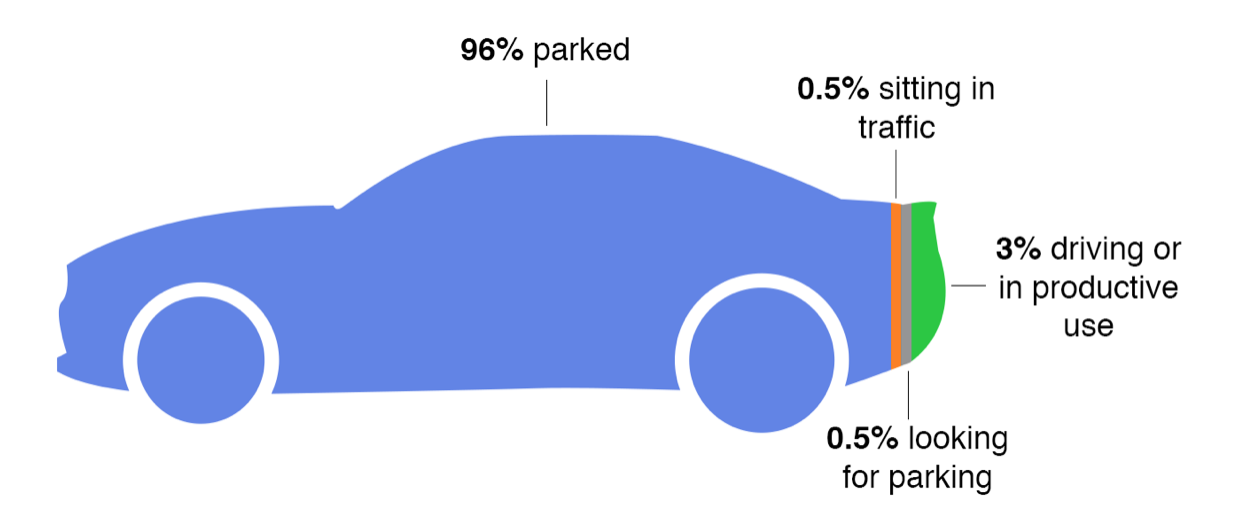

Americans, for example, spend over $2 trillion per year on car ownership — more than we shell out for food. But shockingly, the 250 million cars in the United States spend 96% of the day parked. In other words, there are 240 million cars parked at all times. As Lyft co-founder John Zimmer has observed, BMW doesn’t make the “Ultimate Driving Machine” — it makes the “Ultimate Parking Machine”.

For the American consumer that spends an average of $9,000 per year on their car, ride-sharing offers an attractive alternative. Owning a car means monthly payments, not to mention the cost of gas, dealing with repairs, and searching for parking. Ride-sharing means convenience, on-demand, and affordability.

The changing sentiment is evident in younger consumers who are digital natives. According to Bloomberg industry research, last year, more automobiles were sold to people aged 75 and older than 18-24-year-olds. And the number of young people with a driver’s license has steadily decreased. In 1983, 92% of 20- to 24-year-olds had driver’s licenses. Today it is just 77%.

Look younger, and the shift is even more pronounced. In 1983, 46% of 16-year-olds had licenses. Today it is 24%.

What’s Next

With Uber’s meteoric rise after 2010, many thought this would be a winner-takes-all market. While Uber’s scale offers unmistakable advantages, a few unexpected developments have occurred recently.

In December 2015, for example, Uber’s four major global competitors — Lyft, Ola, Didi Chuxing, and Grab — entered into a partnership where the companies enabled users to book cabs from each other’s apps in all the regions where they operate.

Then, in August 2016, Didi announced that it struck deal to effectively acquire Uber’s Chinese business, merging the subsidiary into Didi’s larger business at a combined valuation of $35 billion. Uber was granted a 20% stake in the new business and Didi, in turn, invested an additional $1 billion into Uber.

If the transaction isn’t sufficiently complex, Didi has also invested nearly $100 million in Lyft, $350 million in Singapore-based Grab, and $30 million in India’s Ola.

AUTONOMOUS

Research into Artificial Intelligence (AI) is as old as computers themselves. During World War 2, British mathematician Alan Turing created the Turing Test — a test that determines whether or not a computer passes the threshold of being intelligent enough to be mistaken for a human. Soon afterwards, the term “Artificial Intelligence” was coined.

The current frontier of AI is “Deep Learning” — a process where computers “teach” themselves concepts and tasks by crunching large sets of data. It’s way of getting computers to “know” things when they see them, by producing rules that programmers cannot specify. For example, Facebook’s facial recognition algorithm, Deep Face — which can recognize human faces with 97% accuracy — was created by feeding computers with millions of images of faces.

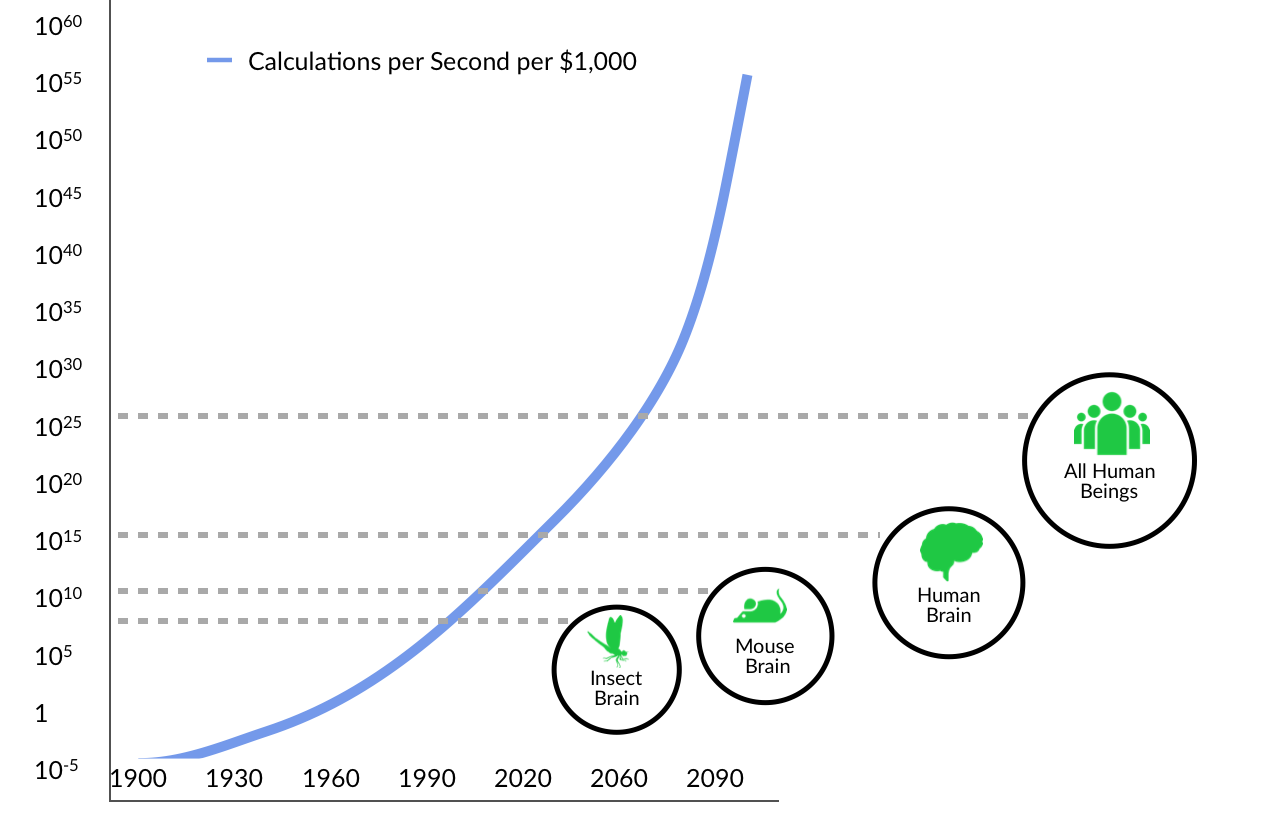

This process, while conceptually developed in the 1960s, wasn’t possible until recently for two reasons. First, until recently, there weren’t enough digital artifacts (photos, in the case of Facebook’s Deep Face) to train computers. But even if there had been, the cost of computing was prohibitively expensive and the capabilities were too limited.

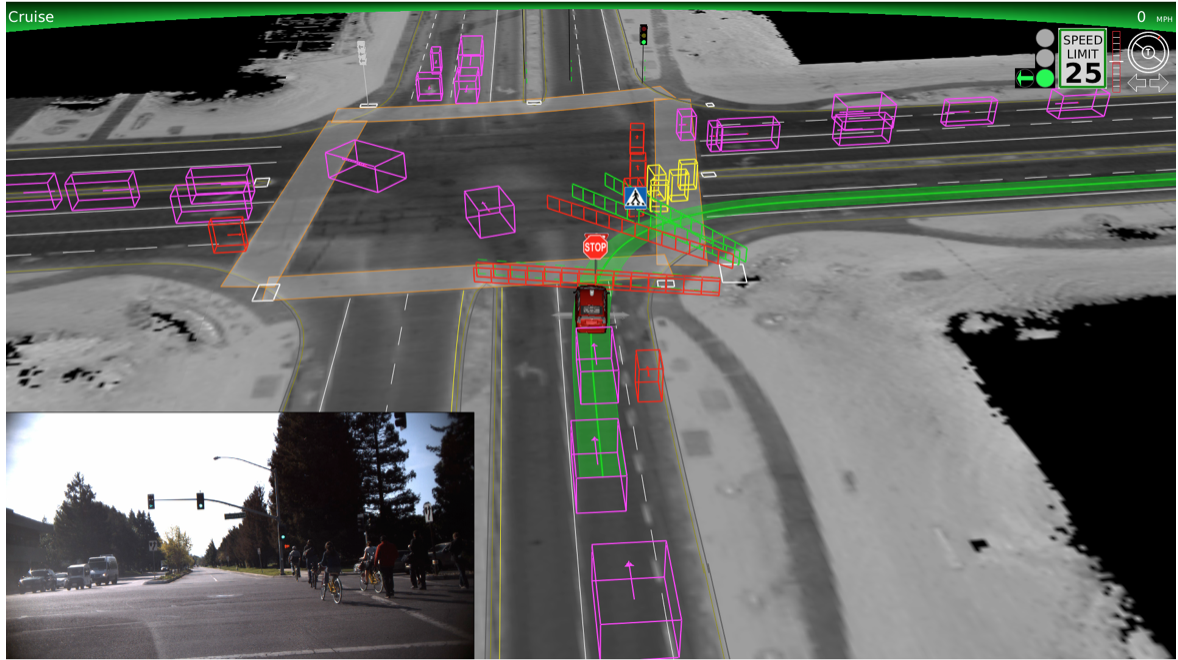

Moore’s Law — which predicted that computing power would double every two years (with costs halving every two years) — has made Deep Learning a reality. Applied to transportation, Deep Learning is enabling the creation of smart, autonomous vehicles that are able to learn from, and adapt to, their surroundings.

Why It Matters

In 2004, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched a Grand Challenge series, a multimillion-dollar competition for university robotics teams to design autonomous vehicles. A rivalry quickly developed between Stanford and Carnegie Mellon (the schools traded the top spots in the first two years of the competition) that shaped the early future of self-driving cars.

Sebastian Thrun, the leader of Stanford’s winning team, took a leave from the university in 2007 to work on Google Street View, and later founded the company’s self-driving-car project. In 2015, Uber announced a partnership with Carnegie Mellon to launch the Uber Advanced Technologies Center to develop and deploy self-driving cars through its ride-sharing platform. The first generation of vehicles, designed by Volvo, debuted on the streets of Pittsburgh in September.

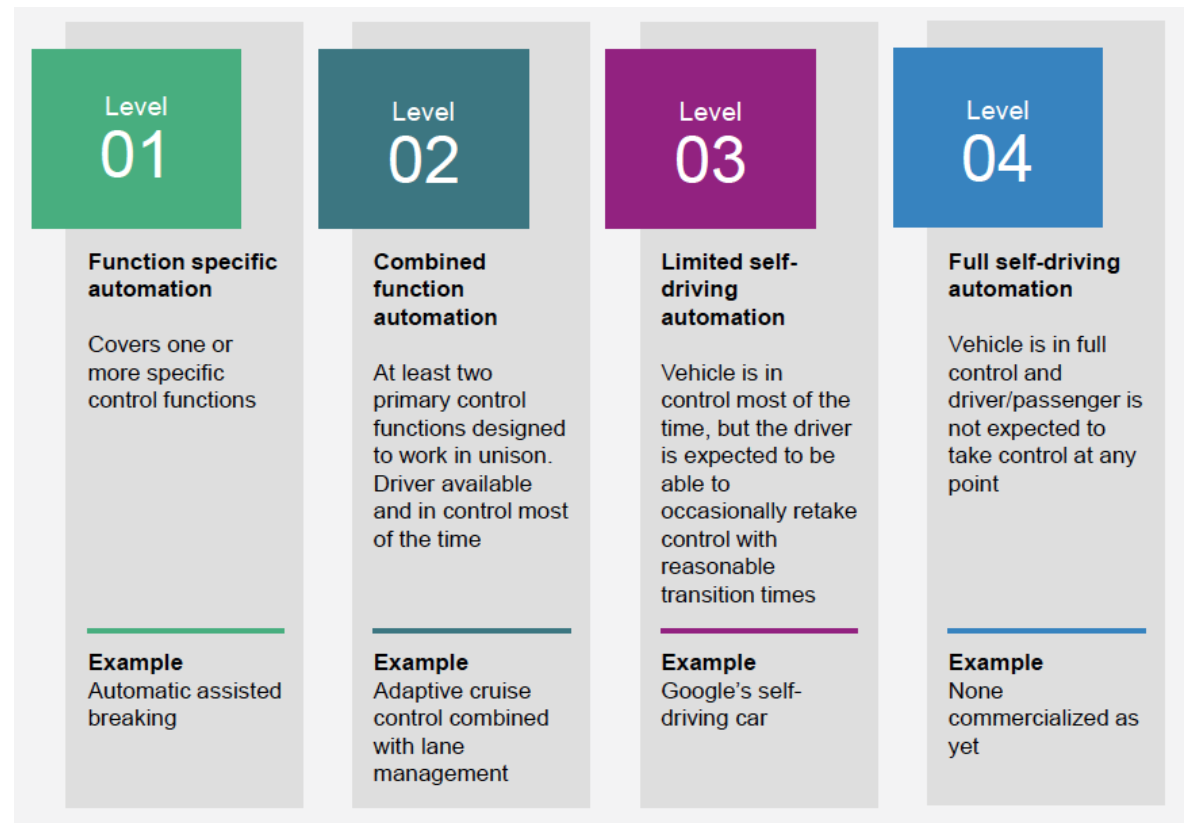

Alphabet’s (Google) highly publicized self-driving car initiative served as a starting gun for the entire industry because it leapfrogged incremental ideas. As opposed to focusing on assisted driving, the company instead committed to creating a car without a steering wheel or pedals. It was the stuff of science fiction and it captured the World’s imagination.

As it has increasingly become clear that self-driving cars are within our grasp, everyone it taking notice.

For automakers, it’s a matter of survival. The combination of ubiquitous ride-sharing platforms with self-driving cars calls into question the need to buy a car. It’s why you’ve seen GM invest $500 million in Lyft in a long-term partnership to deploy a network of autonomous vehicles. Ford has announced that it will create a fleet of self-driving cars by 2021 in a shared network. Tesla’s cars are already outfitted with “Autopilot.” The list goes on. (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Lyft)

For technology companies like Alphabet (Google), Baidu, Microsoft, and Apple, cars could be the next great computing platform. Baidu has partnered with the chipmaker nVidia to create an autonomous driving and navigation platform for use by third parties in 2018. Apple’s “Project Titan”, while recently rumored to be scaled back, shares a similar objective.

Ride-sharing platforms are the third leg of the stool. Interestingly, despite high-profile announcements and partnerships from Uber and Lyft, the lesser known nuTonomy was the first to get a network of on-demand, self-driving vehicles on the road, deploying a pilot in Singapore in early September.

What’s Next

As billions of dollars of R&D investment are poured into autonomous vehicles from carmakers, technology companies, and ride-sharing platforms, innovation will accelerate. And we won’t just see the results in consumer cars and services.

Otto, for example, a self-driving long-haul trucking company that was acquired by Uber in August 2016 for $680 million, just made its first journey this week. It delivered 45,000 cans of beer to a Budweiser warehouse after a 120-mile trip.

While projections on the pace of autonomous vehicle adoption vary, Lyft founder John Zimmer offered a helpful analogy in a recent blog post:

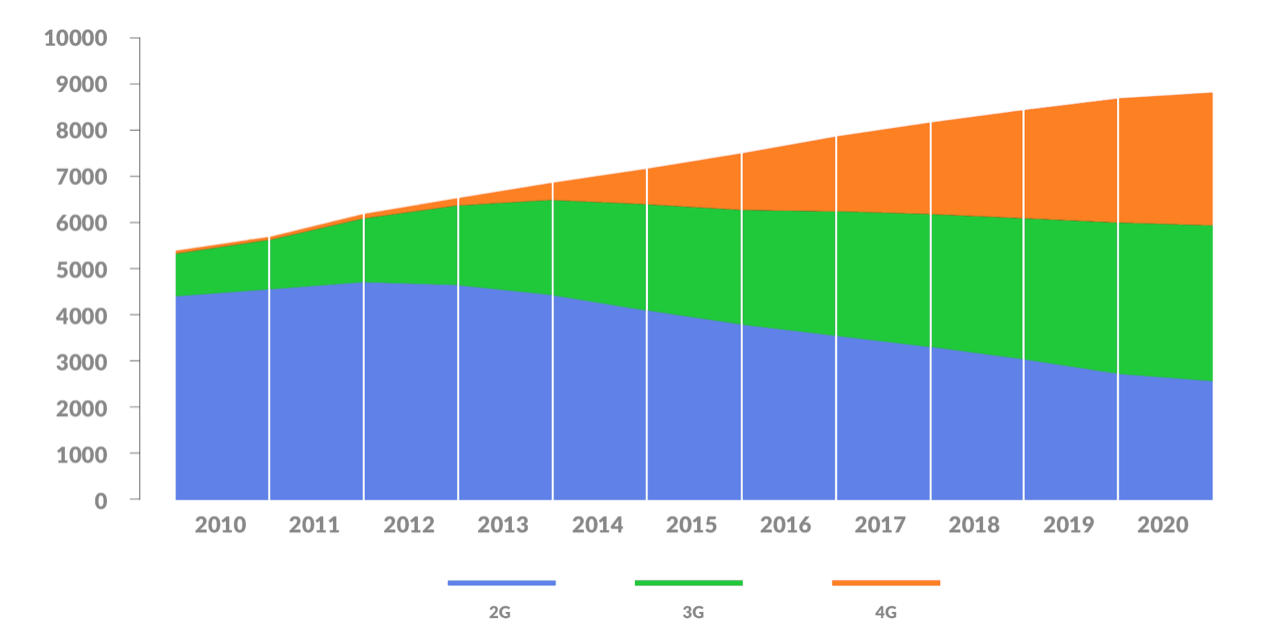

Remember when cell phone coverage transitioned from 3G to 4G? The 4G networks were slowly rolled out, first covering only the largest cities and eventually growing to cover larger and larger portions of suburban areas. This ensures that people are always covered, one way or another. If you spend most of your time in a place that’s only covered by 3G or even 2G, you still have a network to rely on. But as soon as you step into a spot with 4G coverage, you automatically get to try it. Just wait for the upcoming launch of 5G. Future 5G networks won’t be introduced to the world by new companies, they will be rolled out on top of the largest existing networks around the world.

The introduction of autonomous vehicles will follow the same pattern, until its the backbone of mobility.

The next hurdle is to create a regulatory framework for autonomous vehicles to take the road at scale. We anticipate this process will happen incrementally, where self-driving cars are first introduced in designated areas of cities and on specific roads, guided by digital “geofences.”

In the United States, the The Department of Transportation has announced a 15-point safety standard for the design and development of autonomous vehicles. The framework, released in September, calls for states to come up with uniform policies for driverless cars; and clarifies how current regulations can be applied to the technology. Expect the policy debate to heat up as the inevitably of our autonomous future continues to capture mainstream attention.

LOOKING AHEAD

Beyond the large players, a wave of startups is emerging, rethinking how vehicles “see” the road, communicate with “smart” networks, and operate with greater energy efficiency. To date, Venture Capital firms have invested $874 million into auto technology companies. Financings will surpass $1 billion for 2016 if the current pace continues.

But vehicles are just the beginning. The future of mobility is the stuff of science fiction — from on-demand flying taxis to Hyperloops, near-supersonic trains in giant pneumatic tubes that could whisk passengers between Los Angeles and San Francisco in 35 minutes. Read more below in this week’s edition of Bubblin.

—

FBI Director James Comey arrested stocks on Friday with a letter to Congress that indicated he was “just kidding” when he said the Hillary investigation was over last Summer. Markets dropped 1% in sixty minutes, with the NASDAQ finishing down 1.3% for the week and the S&P 500 falling 0.7%. Yields on the the 10-Year Note jumped to 1.85%, driven by more uncertainty and GDP growth being surprisingly strong at 2.9% for the Third Quarter.

With earnings season in full swing, companies like Alphabet (Google), Tesla, TAL, and New Oriental delighting investors. Despite AWS showing 55% revenue growth, Amazon frustrated investors with underperformance, as did Apple. The once growth darling Chipotle continued to provide an upset stomach to shareholders, with same store sales dropping over 20% for the quarter. The stock hit a three-year low.

For “Exhibit A” of what happens when a high multiple growth stock slightly misses a metric, check out GrubHub, which posted 73% earnings growth. New diners “only” grew 19%, so its stock dropped 13%.

This week, Facebook is reporting, with expectations based on analysts estimating 70% EPS growth. Alibaba is also reporting this week, with estimates showing 29% EPS growth and revenue growth north of 50%.

Six companies went public last week. ZTO Express IPO’d at $20 per share, raising $1.4 billion at a market cap of $14.3 billion. The company’s shares dropped by 13% but the end of the week. Blackline also went public at $17 per share, raising $146 million at a market cap of $839M. The company’s shares jumped 39% but the end of the week. Other IPOs included RA Pharmaceuticals, Acushnet Holdings, Myovant Sciences, and Quantenna Communications.

With the U.S. election nine days away, we expect more surprises and more volatility in the Market. Volatility is the long term investor’s friend and we would take advantage of any drops in our favorite names to accumulate shares while they are on “sale”. We remain BULLISH.