Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

Imagine if you had $6 million in cash in a pallet flying through the air, and it was going to smash into the ocean. Would you try to recover that? Yes, yes you would.

— Elon Musk (on recovering a reusable rocket component from a 2017 launch)

You rarely see an entrepreneur pitch a 100x improvement. But in Space we’ve seen 1,000x, and really, we’ve seen 10,000x.

— Steve Jurvetson, Managing Director, DFJ & Board Member, SpaceX

Last week, SpaceX shuttled a commercial satellite into Space, launching and landing a pre-used rocket on the bullseye of a barge floating off the coast of Florida. Ten years ago, not a single element of that statement would have made any sense.

In 2007, the five-year-old SpaceX was still twelve months away from its first successful rocket launch, and six years away from sending a satellite into orbit. Landing a rocket intact didn’t exist, let alone reusing any of its components.

Until SpaceX, the rule with rockets was that what goes up comes down in pieces. And it was a sure bet that those pieces belonged to one of the aeroSpace monopoly — Boeing, Lockheed Martin, or Airbus.

Accordingly, the cost of getting anything into orbit — from satellites to people and supplies — has routinely been upwards of $250 million per launch. It would be like having a commercial aviation industry where planes were flown once and then discarded. The net result has been limited innovation and impossible barriers for would-be new market entrants.

26896.jpg)

But SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, who’s made a habit out of defying gravity, is changing the fundamental economics with reusable rockets — all while “moonlighting” as the CEO of Tesla, which recently surpassed Ford in market value.

The personal computer paved the way for a new category of software companies. Affordable computing infrastructure like Amazon Web Services (AWS) spawned scores of cloud applications. Today, reusable rockets are poised to drive down cost and catalyze a variety of Space applications — from travel to satellite-enabled logistics, business intelligence, and security. Investment and innovation are following.

STATE OF PLAY: SPACE

Global Spending

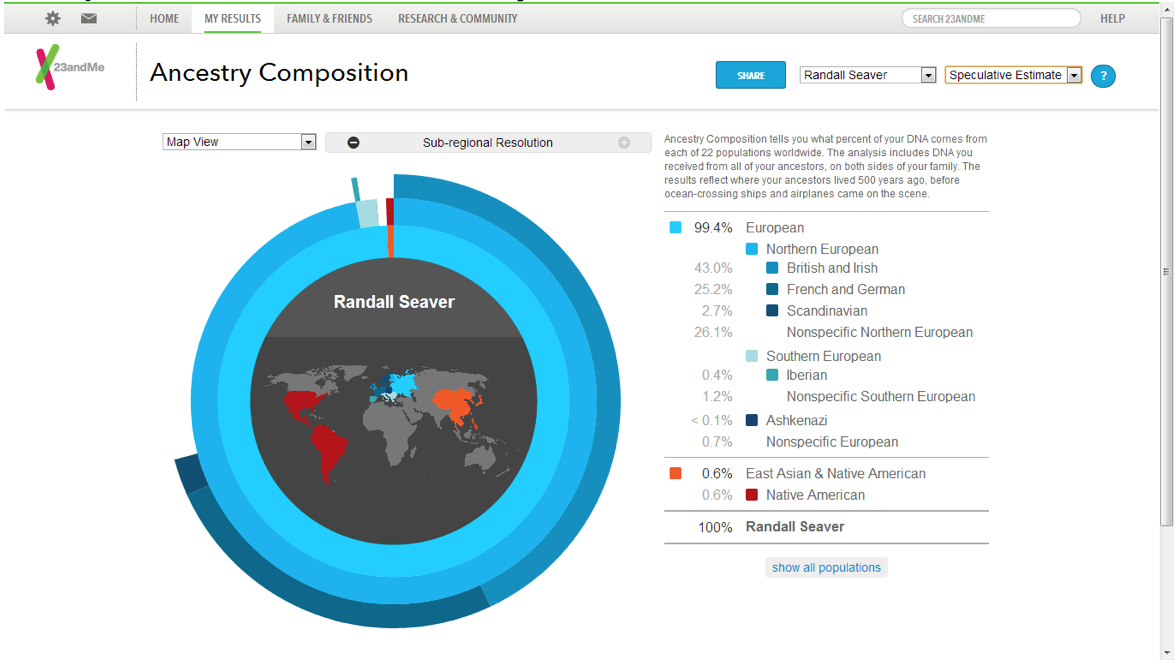

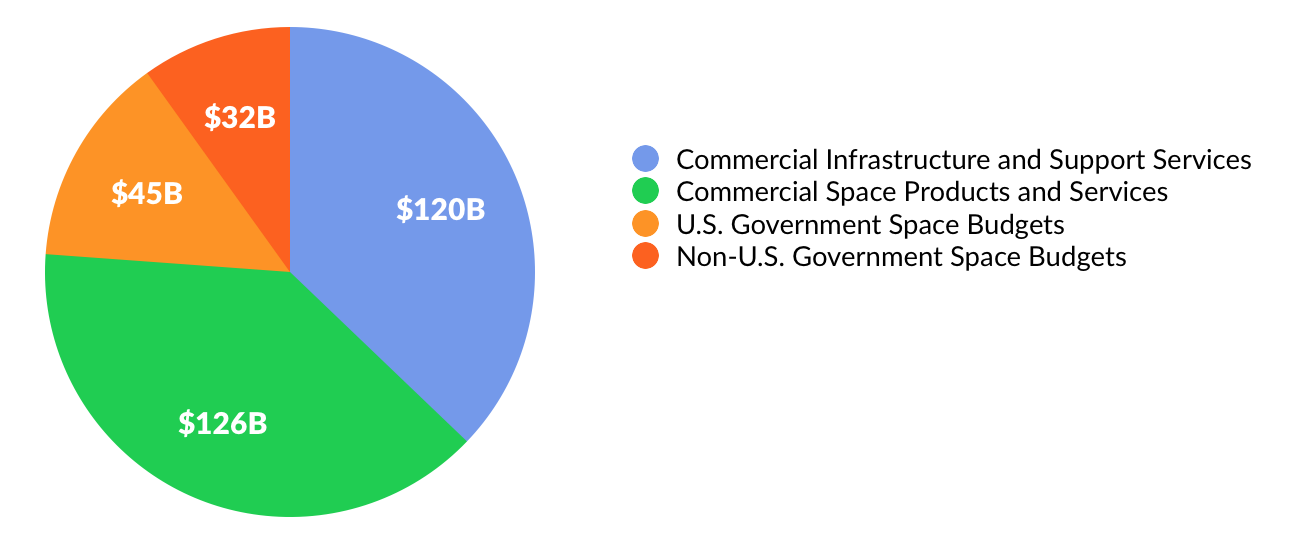

The global Space economy comprises approximately $323 billion in annual spending. Key components include launch and ground services, satellite manufacturing, satellite television and communications, government exploration, and military spending.

Source: Space Foundation

*Most recently reported industry data is from 2015

Revenues from commercial sectors represented over three quarters of all global economic activity related to Space. Commercial Space products — including telecommunications, broadcasting, and Earth observation — was the largest sector, growing by 4% year-over-year to reach $126 billion.

To date, global Space innovation has effectively existed as a closed platform built on funding from government agencies — headlined by NASA, which spends approximately $20 billion per year on a variety of initiatives. The net result is that a small ecosystem of multi-billion dollar aeroSpace companies has become a fixture, subsisting for decades on government contracts.

Companies like Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Airbus — together commanding more than $200 billion in market value — have provided a full range of services to get people, satellites, and supplies into Space.

*Founded in the 1995 merger of Lockheed Corporation (est. 1912) and Martin Marietta (est. 1961)

**Founded in the 2015 merger of Orbital Sciences Corporation (est. 1983) and Alliant Techsystems (est. 1990, spun off from Honeywell)

Investment Activity

New entrants to the Space innovation economy are unlocking economic opportunity and redefining the realms of possibility at a rapid pace. And they are serving notice to aerospace incumbents. As Elon Musk observed in a 2014 interview with the Financial Times:

When I founded SpaceX, development in Space transport and rocket technology had essentially frozen. The Russians had the same rockets they were using when the Soviet Union fell; the US had Boeing and Lockheed rockets that were designed in the last century. The only way technology in any field improves is a result of new entrants. Otherwise, there’s little incentive for the incumbents to get better.”

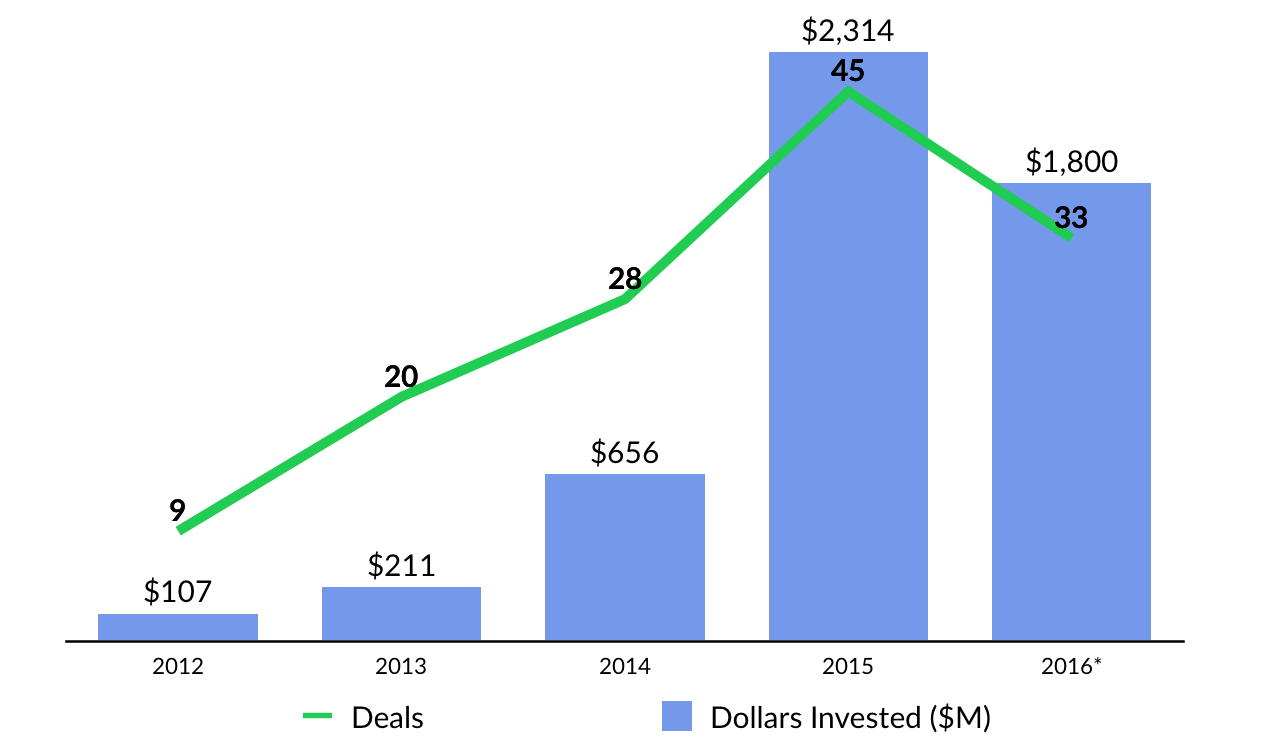

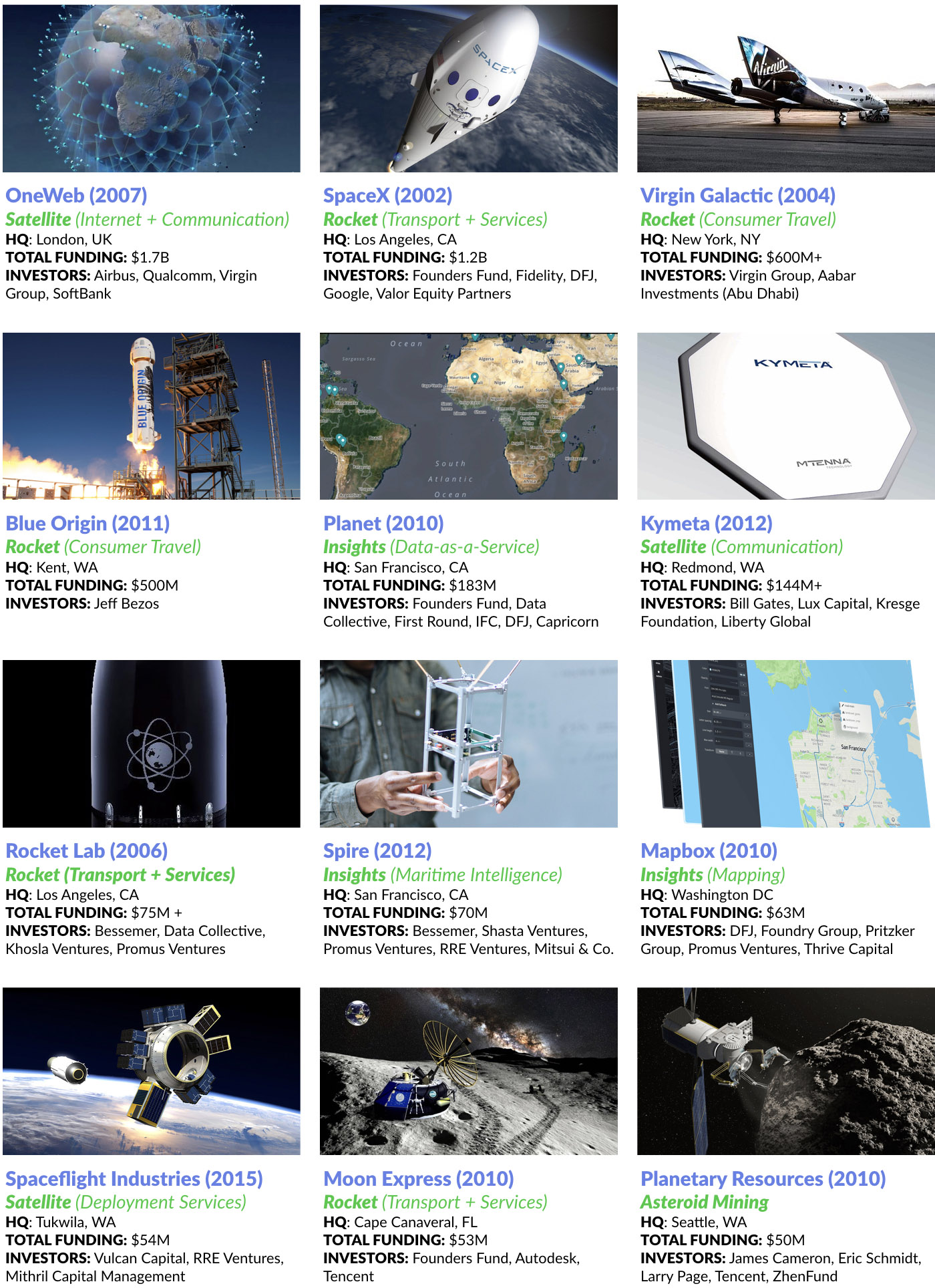

Investment activity has followed. Many of the early headlines have centered on high-profile aerospace ventures from a billionaires club, including Jeff Bezos (Blue Origin), Richard Branson (Virgin Galactic), Elon Musk (SpaceX), and Paul Allen (Vulcan AeroSpace).

But VCs are also betting big. In 2015, investors poured a record $2.3 billion into Space startups, with SpaceX raising $1 billion and OneWeb and O3B Networks raising $500 million and $460 million, respectively.

Source: CB Insights, GSV Asset Management

* Estimate

Notable 2016 financings included London based micro-satellite company OneWeb, which raised a $1.2 billion mega-round from SoftBank in December 2016, surpassing SpaceX as the most well-funded Space startup. Satellite manufacturer Kymeta’s raised $62 million (Series D Financing) and Space-debris removal company Astroscale’s raised $35 million (Series B Financing).

Top Space investors include Bessemer Venture Partners, Fidelity (by virtue of an estimated $100+ million position in SpaceX), Founders Fund, and Khosla Ventures. M&A activity has been headlined by Alphabet, which acquired Terra Bella (formerly Skybox Imaging) for $500 million in 2014, and SoftBank, which invested over $1 billion into OneWeb in December 2016. SoftBank’s intent is to use OneWeb’s satellite “constellation” to enhance high speed internet capabilities for key telecommunication holdings like Sprint.

In November 2016, Starburst Ventures raised a $200 million debut fund to back Space startups as extension of the Starburst Accelerator, which was founded in 2012. Starburst Ventures will aim to back 35 startups over the next three years according to CEO and founder Francois Choppard, a former aviator and Airbus engineer.

KEY SEGMENTS OF THE SPACE MARKET

1. Rockets + Spacecraft

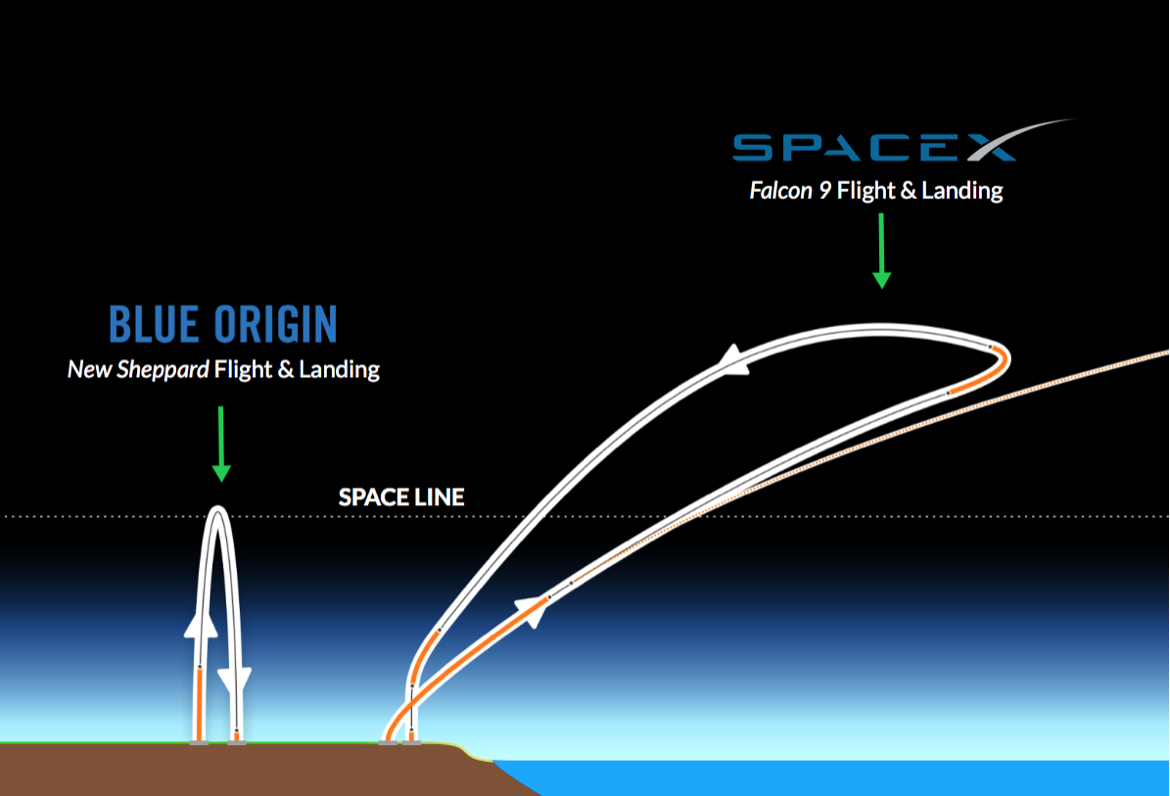

Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos-backed Blue Origin are shattering the old Space cost paradigm by making rocket reusability a reality. In November 2015, Blue Origin’s New Shepard became the first rocket to stick a controlled, upright landing after a brief visit above the Space line. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 followed suit weeks later. Bezos commented on SpaceX’s landing on Twitter saying, “Welcome to the club!”

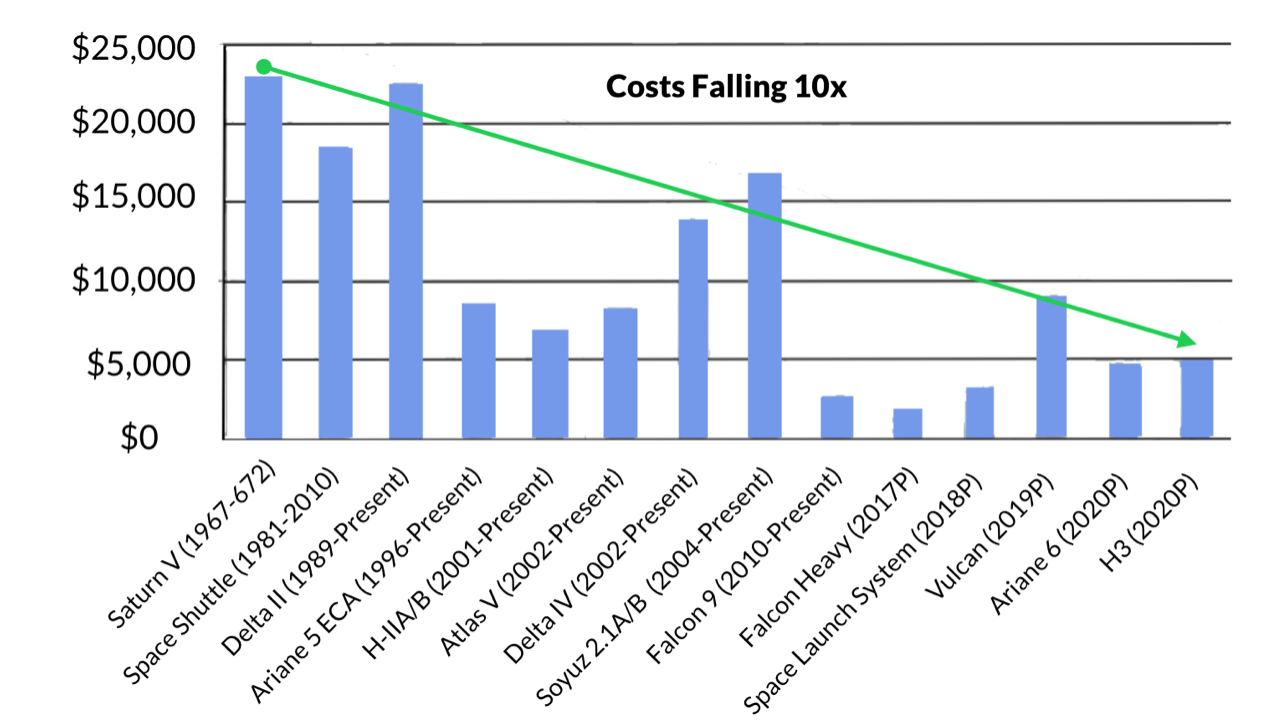

All told, Goldman Sachs estimates that improved rocket design and logistics have driven down launch costs 10x over the last decade — more than the entire previous history of Space exploration combined.

The cost-to-LEO metric, which measures the cost to for one rocket to launch 1 kilogram of cargo into low Earth orbit, is used to gauge the differences between launch cost between rockets.

During the 1960s, Saturn V’s cost-to-LEO was between $20,000 to $25,000. Today, SpaceX’s Falcon 9’s cost-to-LEO is between $4,000 to $5,000. SpaceX hopes to bring the cost-to-LEO even further down to $1,7000 with their new Falcon Heavy rocket, set to take off in late-2017.

Beyond SpaceX and Blue Origin, companies like Rocket Lab and Vector are also aiming to develop light-weight, cost effective, commercial rocket launch services. Rocket Lab’s Electron launch vehicle was designed specially to service to the small satellite market and currently counts NASA, Moon Express and Spire as customers. Vector, founded by early SpaceX employees, designs and flies low-cost, rapid-launch rockets and plans on achieving cost-efficiency by launching more than 100 a year.

An adjacent group of companies focused primarily on tourism are producing Spacecraft. Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic aims to fly customers to Space in 2018 using Virgin’s six-passenger VSS Unity, at a cost of $250,000 a seat. According to Bloomberg, Jeff Bezos plans on selling $1 billion of Amazon stock annually to fund Blue Origin’s vision for Space tourism. Not to be outdone, SpaceX has its sights to send two tourists on a trip around the moon late 2018.

Satellites

Over the past decade we have become increasingly dependent on satellites to complete a variety of daily activities, from communication to commuting. Smartphones and tablets used by billions of people are powered by processors that rely on satellite-enabled position, navigation, and timing (PNT) functionality. Apps like Google Maps, or Uber and Lyft wouldn’t work without PNT. (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Lyft.)

According to the Space Foundation, 262 satellites were launched in 2015. By contrast, between 2000 and 2010, only 108 satellites were launched per year on average. Two key factors are driving this trend.

First, a proliferation of companies providing satellite launch and management services — including Vulcan Capital backed Spaceflight Industries — is making it more efficient and affordable for companies to place satellites into orbit.

But a broader trend is the miniaturization of satellites, enabled by advanced components developed by companies like Accion Systems. Ranging from the size of a small shipping box to a refrigerator, Nanosatellites, or “Nanosats,” are significantly smaller and affordable than traditional satellites.

A variety of startups have raised money to deploy “constellations” of these satellites into low-Earth orbit in an effort to upend existing players such as Airbus and DigitalGlobe for applications like Earth imaging and Internet connectivity.

Founded by Greg Wyler, OneWeb plans to deploy a micro-satellite constellation in order to provide global high-speed, low latency broadband access. The company’s goal is to put more than 2,600 satellites in orbit by 2019. It could be a blue print for brining the digital divide that has left over half of the World’s population without Internet access.

37477.jpg)

In December 2016, OneWeb completed a $1.2 billion financing led by SoftBank. It is using the proceeds to build the World’s first high volume satellite production facility in Florida. At scale, the factory will be able to produce 15 satellites per week at a fraction of current costs.

OneWeb is also set to merge with competitor Intelsat, following SoftBank’s $1.7 billion investment to acquire nearly 40% of the combined entity. The deal should provide advantages for Softbank’s other portfolio company, Sprint, which will be able to tap into a next generation satellite network to deploy high speed internet in previously unreachable corners of the Earth.

Insight + Logistics

As James Crawford, the founder and CEO of satellite imaging startup Orbital Insight has observed, “In the old days, when satellites were like mainframes, incredibly expensive, if you managed to get an image, you probably spent $10,000 on them.” New satellite technology fundamentals, coupled with declining costs for computing power and data storage, have changed the paradigm.

Lower-cost satellites can now be deployed to capture enormous quantities of imaging data that can be applied across a wide range of business functions. Weather services, for example, can utilize sensors on Nanosats to gather more timely information, to the benefit of farmers, transportation and logistics businesses, and rescue workers. Government agencies can analyze imagery to monitor deforestation and environmental impact over time. The list goes on.

With nearly 150 “Dove” nanosats in Space, Planet has the largest fleet of Earth imaging satellites in the market — among private companies and government agencies alike. In February 2017 alone, Planet launched 88 satellites into orbit at once, enabling it to photograph every square mile of Earth’s land mass daily — a total of 57 million square miles, up from roughly 19 million square miles pre-launch.

Planet recently acquired Alphabet’s satellite imagery subsidiary Terra Bella, a company that it purchased in 2014 for $500 million. As part of the deal, Alphabet will take a stake in Planet and it has agreed to purchase satellite images from the company for five years.

Planet, in turn, will add Terra Bella’s satellites to its fleet, which capture images six times as detailed as Planet’s. With this acquisition, Planet will be able to scan the world in medium resolution to detect macro changes, while using Terra Bella’s high-resolution satellites to pinpoint and track developments on a finer scale.

Founded in 2012, Spire is on a mission to eradicate the “data dead zones” that exist across the Earth’s oceans. More than 50 nautical miles from any coastline, connections to the modern World are effectively severed. Tracking systems for ships leave mariners and the cargo they transport vulnerable, while letting illegal activity go unchecked. You can track a UPS truck to a city block, but cargo ships carrying millions of dollars worth of goods remain elusive. Spire is changing that.

Data from Space will continue to diffuse into broader industries. Mapbox, which develops custom maps for companies like Foursquare, Pinterest, The Weather Channel and Uber, entered the autonomous car market with Mapbox Drive in 2016. Through Drive, Mapbox will provide car companies the software to enhance autonomous driving capabilities by integrating navigation data with real-world driving conditions derived from satellite observations.

In another context, investors are using satellite data to monitor traffic to large brick and mortar retailers as a leading indicator for financial performance. Based on a million satellite images, for example, Orbital Insight conducted a historical analysis on cars in the parking lots of Ross Stores. It successfully forecasted the retailer’s better-than-expected quarterly performance. The applications for satellite data will continue expand rapidly across industries as technology and services mature.

WHAT’S NEXT: NEW FRONTIERS

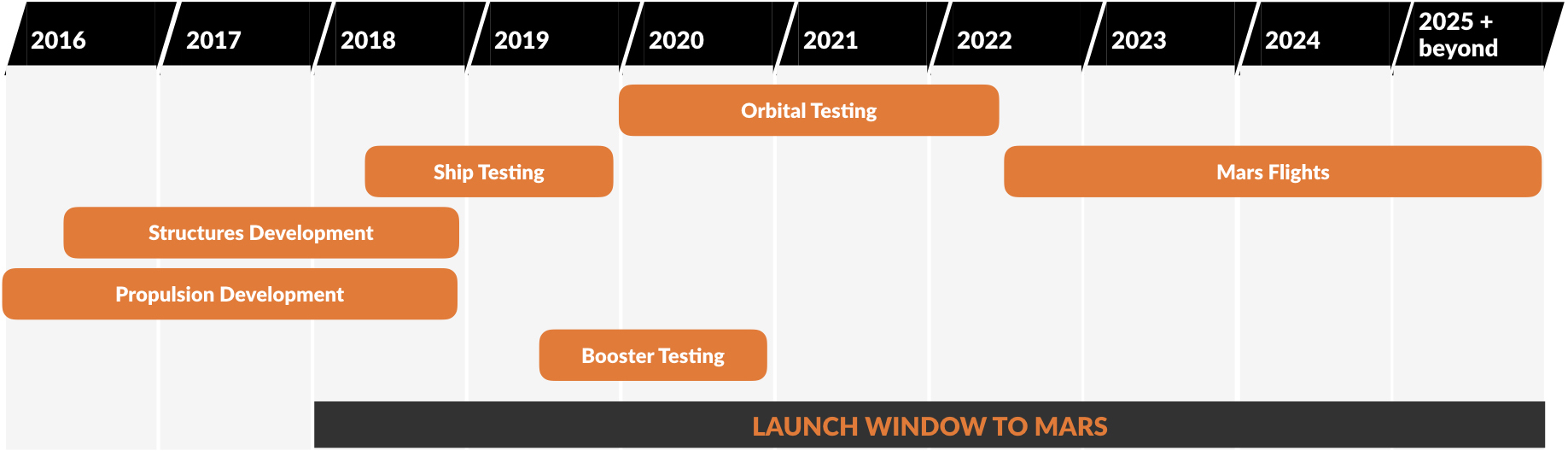

Elon Musk has grabbed headlines with a commitment to colonize Mars in his lifetime. His goal is to have humans on the Red Plant by 2022. Musk even recently enlisted the services of Jose Fernandez — the acclaimed costume designer for superhero movie franchises including Batman and Captain America — to design “stylish and heroic” Spacesuits for the company’s astronauts.

This isn’t PR fodder. SpaceX’s Interplanetary Transport System already lays out a framework to bring 100 people to Mars per trip in the early going. Musk’s ultimate vision is to have a Martian city of millions, seeded by tens of thousands of trips over the span of 40-100 years.

Beyond interplanetary colonization, as entrepreneurs continue to apply new ideas and technologies to Space, we expect a drumbeat of game-changing businesses to emerge.

Companies such as Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries are developing the capability to mine resources from asteroids. A steroids are rich in water, which could be converted into rocket fuel refill rockets in Space. That might be considerably cheaper than spending $10,000 per pound to launch resources into low Earth orbit and beyond.

Asteroids are also rich in precious metals. Goldman Sachs estimates that the value of platinum on an asteroid the size of a football field to be between $25-50 billion. The next “gold rush” might be in the sky.

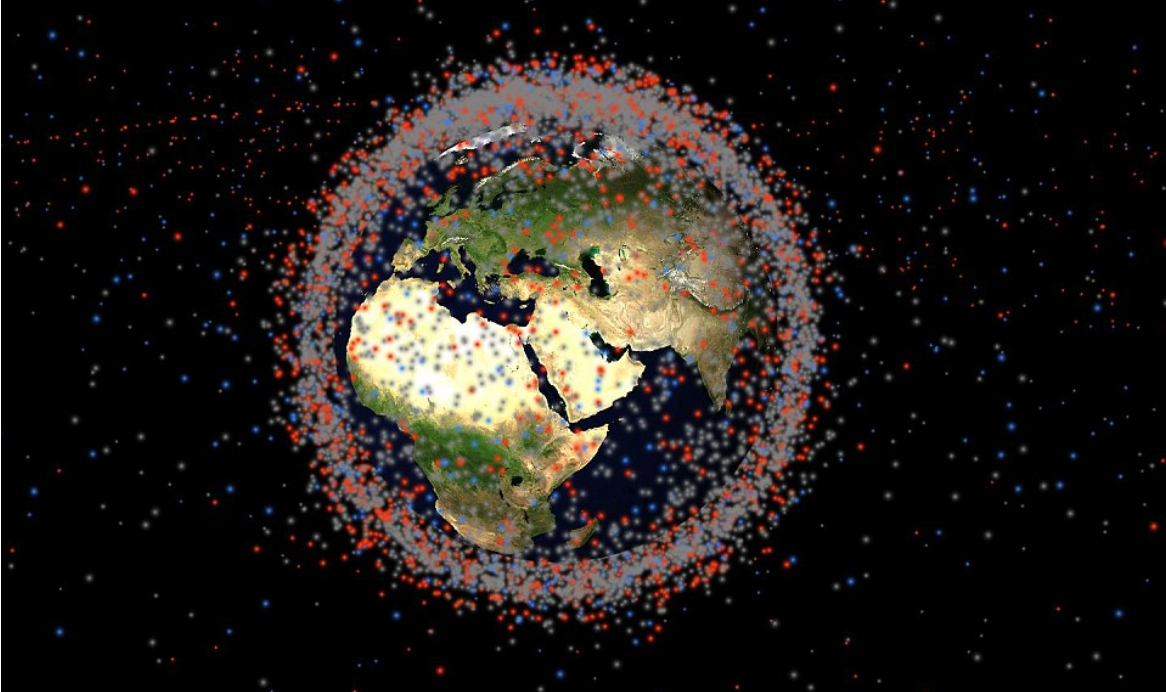

Over the past fifty years, low Earth orbit has been littered with Space debris. The United States Air Force tracks up to 23,000 pieces of “junk” that are large enough to be detected from the ground. With increasing Space activity, the risk of dangerous collisions with satellites and manned aircraft is increasing. Moving at rates upwards of 17,000 miles per hour, even the tiniest pieces of debris are deadly projectiles.

Mitsunobu Okada, the founder of Astroscale, aims to solve this problem with a service that is designed to intercept and remove debris from low Earth orbit. Astroscale does this by using a glue-like adhesive that will stick to debris and drag it out of orbit, burning up upon re-entry to Earth. Other agencies, including the U.S. Air Force, have proposed similar concepts using lasers, “harpoons,” and nets.

Ultimately, we are just beginning to sow the seeds of a much broader Space innovation economy. A little more than a century ago, on January 1, 1914, the commercial aviation industry began with a single flight in Florida. Since then, commercial aviation has transformed the World in ways that were unimaginable then. Today, a generation of inventors and builders are looking to Space.

We’re headed to infinity and beyond.