Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

Last week Alphabet announced that it was leading a $1 billion financing for Lyft that values the company at $11 billion. (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Lyft)

Noteworthy? Sure. But first consider a few points of context in no particular order.

In May, Lyft announced a partnership with Waymo — an autonomous vehicle developer spun out of Google — to bring self-driving cars to market through its ridesharing network. So there’s some continuity here.

But Alphabet is also a major shareholder in Uber, which is now valued at over $68 billion. Waymo, incidentally, is currently seeking about $2.6 billion from Uber in a claim that the company stole trade secrets in conjunction with the hiring of a former Waymo employee.

And then there is China’s Didi Chuxing. The world’s largest ridesharing platform by volume and second-most-valuable private company has backed both Lyft and Uber, as well as every other notable ridesharing platform across Southeast Asia.

What’s happening here? Let’s rewind.

STATE OF PLAY

Sometimes the “early bird gets the turd.”

Carey International was Uber before Travis Kalanick was born. Listed on NASDAQ in what seems like a century ago, Carey created a black car network spanning 1,000 cities around the globe. Effectively it was a brand, an “800” number, and a scheduling service. Sound familiar?

Uber doesn’t own any of the cars in its network. The drivers are independent. Carey should have been Uber, but they lacked the imagination to see the impact that smartphones could have on their business. Carey launched its first app in 2014 — five years after Uber had taken the world by storm.

The ridesharing industry has taken shape rapidly across a few key phases, catalyzed by the launch of the iPhone in 2007. Beyond its groundbreaking hardware, the iPhone ushered in an “app economy” that enabled transformative new software applications to go from idea to millions of customers seemingly in the blink of an eye.

In many ways, ridesharing is the original “Killer App.”

In the old model, you literally “catch” a cab. You stand on the edge of the street, put your hand up in the air while competing with other would-be riders, and pray for a car to swerve to a stop in front of you. Taxi drivers, meanwhile, troll around blindly for fares, relying on dead reckoning and luck to find passengers.

34172.png)

In the new world, with the click of a button, your ride appears where you want it, when you want it. You don’t need physical money — or even a credit card for that matter — to pay your driver. It’s all in the app.

And a transparent review process ensures that drivers treat their customers well. The better the service, the higher the star rating a driver receives — which in turn translates into a higher likelihood of being connected with riders. Similarly, passengers that consistently demonstrate bad behavior — from no-shows to disorderly conduct — can be removed from a ride sharing platform based on driver feedback.

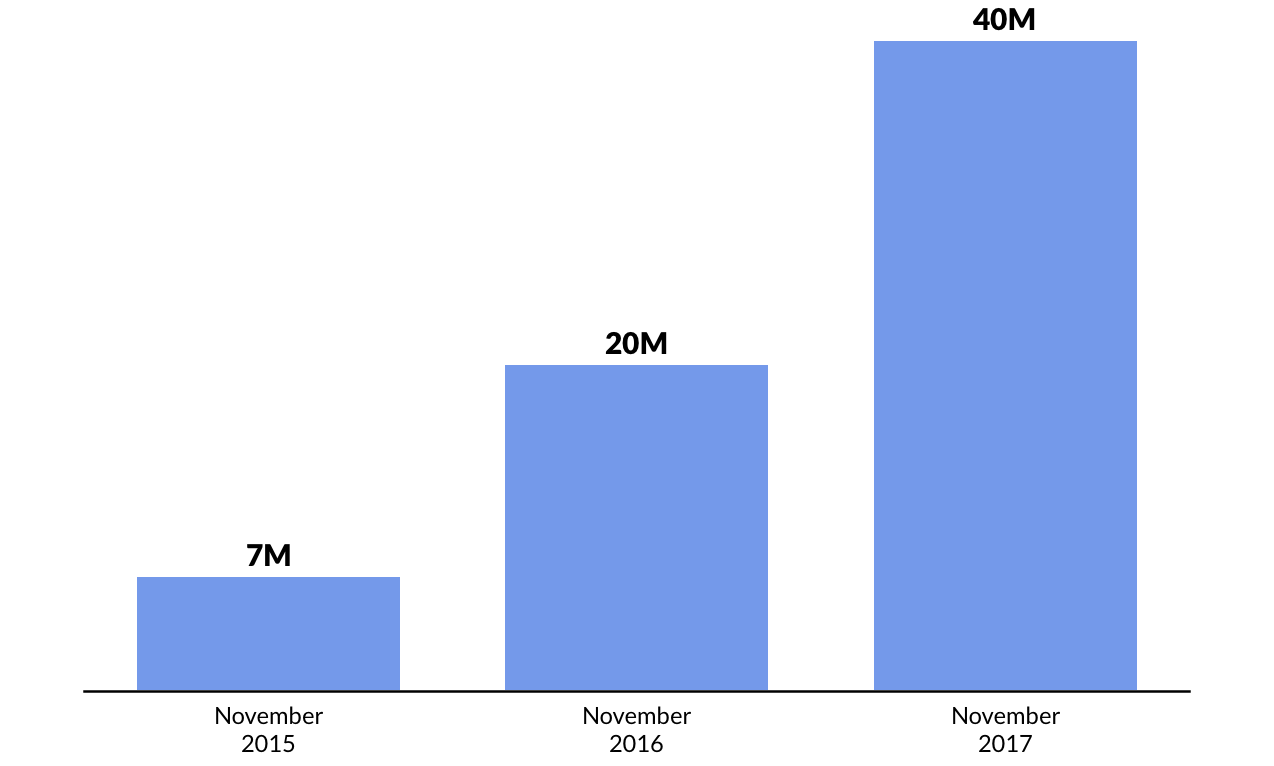

Just how “killer” are ridesharing apps? Uber has completed over five billion rides since it launched in 2009. Didi completes an estimated 40 million rides per day. Lyft, Uber, Didi, Ola (India), Grab (Southeast Asia), and Go-Jek (Indonesia) have raised a combined $40 billion and are collectively valued at over $140 billion.

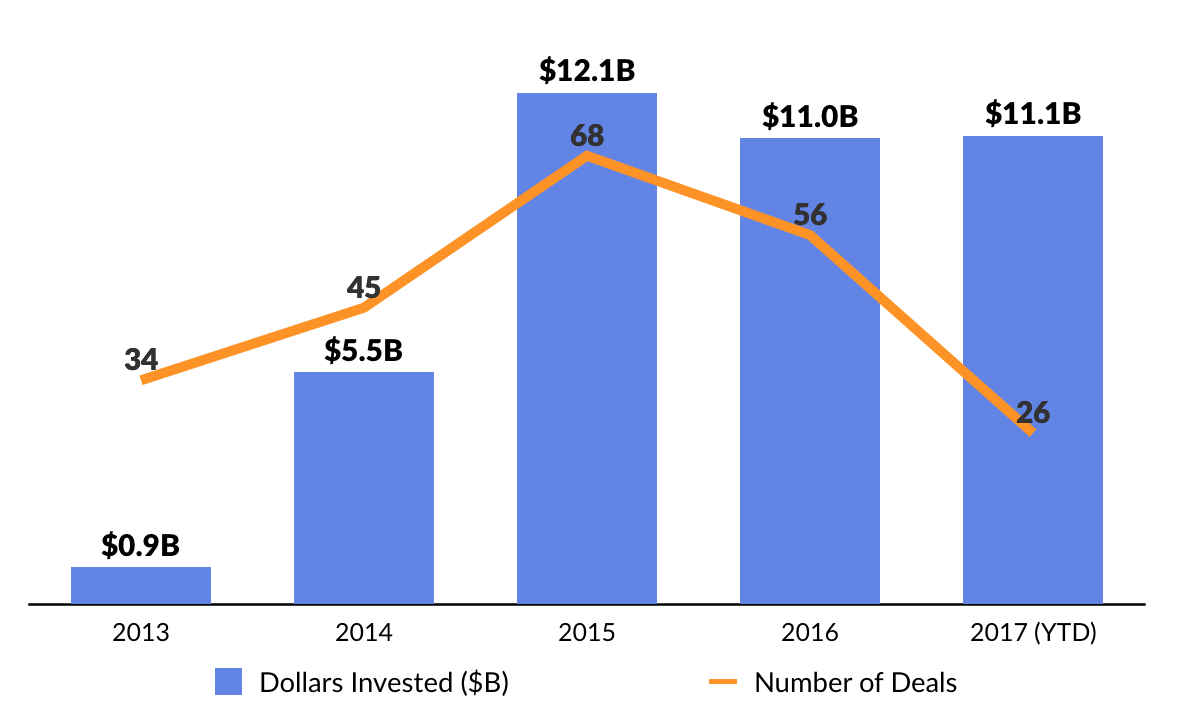

Investment Activity

Since 2015, investors have poured over $10 billion per year into ridesharing companies. Uber, the most valuable startup in the world, was last valued at $68 billion and has raised over $11.5 billion. Chinese behemoth Didi, the second-most-valuable Unicorn ($50 billion), has actually out-raised Uber, bringing in approximately $15.7 billion.

Globally, a crop of newly-minted ridesharing Unicorns have emerged in key geographies around the world as entrepreneurs and investors have eagerly reaped the rewards of a “rapid follower” strategy — as opposed to the classic first-mover advantage.

In many cases, investors are playing the field. Softbank, for example, has invested over $6 billion into Didi, Grab, Ola, and Brazil’s 99. It is currently seeking a $10 billion investment in Uber.

KEY TRENDS TO WATCH

1. Winner Take Some?

Technology in general, and the Internet in particular, is all about disproportionate gains to the leader in a category. It’s often a winner-takes-all game.

The digital tracks that have been laid over the last 25 years have paved the way for technology startups to create dominant positions in a variety of categories, including Facebook (Communication), Alphabet (Search), Amazon (E-Commerce), and Airbnb (Hospitality).

At one point it appeared that Uber was positioned to run away with the global ridesharing industry. But today, a “winner-takes-some” picture is emerging, driven by local regulatory and competitive dynamics, as well as aggressive investor appetite to back the global “copycats.”

The rise of China’s Didi is instructive. Founded in 2012 — three years behind Uber — Didi managed to capture over 80% of the Chinese ridesharing market by 2015 while raising over $800 million from a global syndicate of growth investors, including Temasek, Tencent, and DST. That year alone, the company announced that it had completed 1.4 billion rides. Around that same time, Uber announced it completed its one-billionth since inception.

Fast forward to August 2016 and Uber capitulated in its conquest for the Middle Kingdom, selling its China operation to Didi after burning an estimated $1 billion per year to compete in the market.

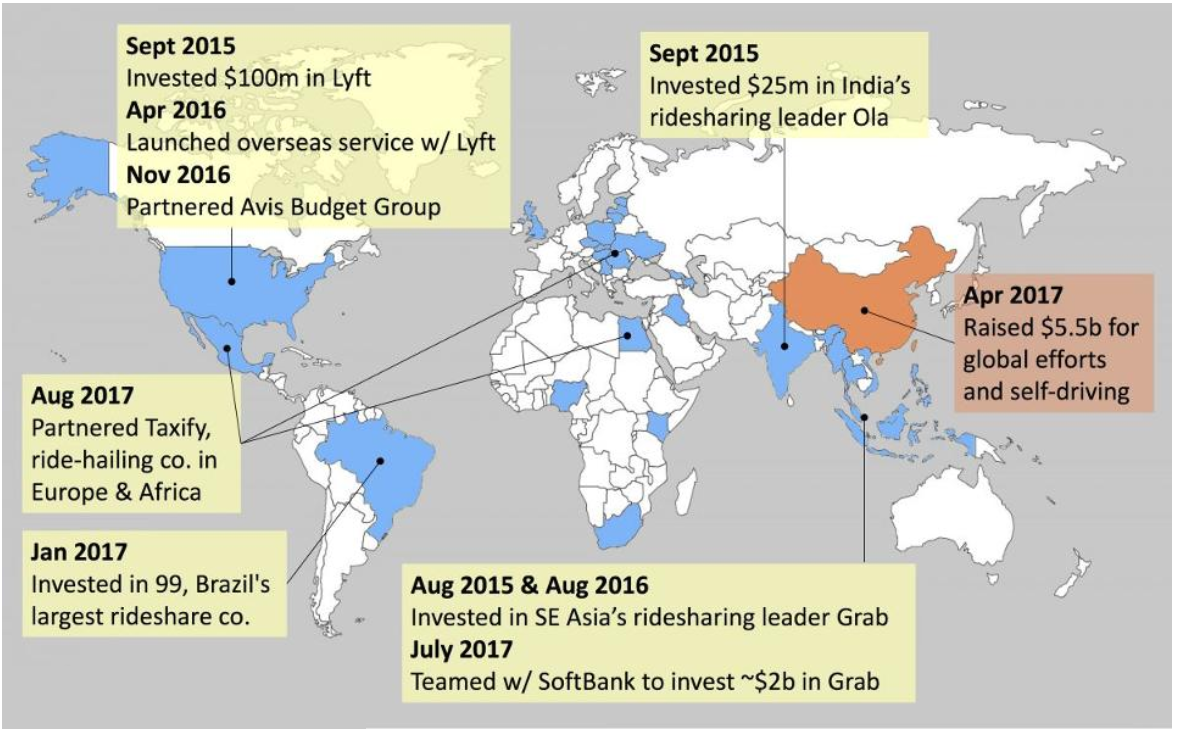

Today, Didi is thinking global, raising an astonishing $5.5 billion in April to fund its growth. But instead of “landing and expanding,” Didi is strategically partnering with — and aggressively investing in — regional ride-sharing companies.

To date, Didi has backed Lyft (United States), Uber (in conjunction with its acquisition of Uber China), Careem (Middle East), 99Taxis (Brazil), Ola (India), Taxify (Europe), and Grab (Southeast Asia).

2. Brands Still Matter

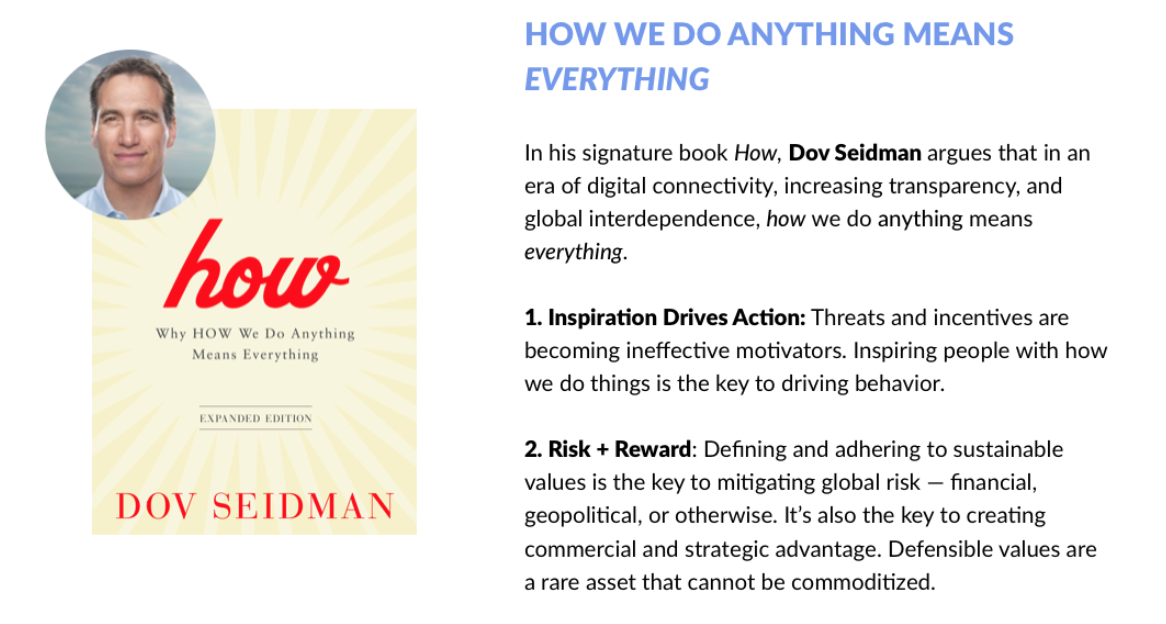

In his signature book How, Dov Seidman makes the case that in an era of digital connectivity, increasing transparency, and global interdependence, “how” we do anything means everything.

There are three fundamental ways to drive human behavior. You can coerce, incentivize, or inspire. Coercion and incentives rely on external rewards (Carrots) and punishments (Sticks). But in an interconnected world, the limitations of Carrots and Sticks are quickly becoming clear. Rules cannot keep pace with technology innovation — a challenge that China has grappled with as it seeks to limit the ability of social networks to amplify political unrest.

On the other end of the spectrum, the return on incentives has declined as increasing connectivity and access to information enable people to find better “deals” elsewhere. It’s getting harder to buy loyalty.

Inspiration, Seidman argues, is the new difference-maker. Accordingly, a company’s ability to define and adhere to a sustainable value set is the key to creating commercial and strategic advantage.

According to research from PR powerhouse Edelman, U.S. consumers report that when quality and price are a wash in competing products, a company’s “social purpose” is the most important factor in their purchase decision. Nearly 44% of people were even willing to pay a premium for the products of companies that support a “good cause” and 62% indicate that they will not buy a brand if it fails to meet societal obligations.

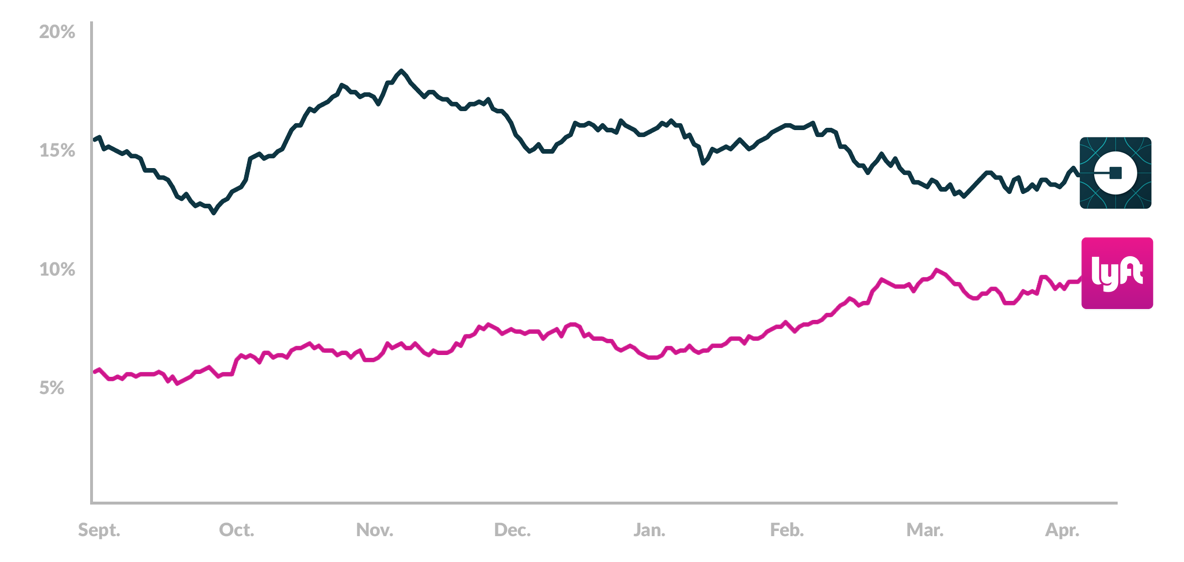

Uber’s recent series of high-profile public missteps — culminating in the departure of CEO Travis Kalanick — coupled with Lyft’s gains in competitive market share is a case in point.

In a 2017 report published by Quartz, the number of U.S. consumers who said they would consider taking Lyft jumped to 9.6% in Q1 2017, up from 5.6% in Q4 2016. Uber fell to 14% from 18% in the same period. In January, Lyft announced that it delivered 163 million rides in 2016, more than tripling its 2015 total. It has launched in over 100 new cities in 2017 to date, and in March the company reported that its growth was accelerating in every market across the country.

While Uber has created a culture and brand focused on World domination, Lyft’s competitive advantage is its mission and its emphasis on creating a unique experience. Co-founders Logan Green (CEO) and John Zimmer (President) created the company with the goal to reduce traffic congestion and pollution while improving the quality of urban life.

Zimmer — who not coincidentally graduated top of his class from Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration — was the brainchild behind a brand that encourages passengers to sit in the front seat and “fist bump” drivers at the beginning of each ride. Lyft has always been about more than getting to your destination quickly, which is table stakes. A recent ad campaign sums up the contrast with Uber perfectly.

Last week’s announcement that Alphabet’s Capital G investment arm led a $1 billion round in Lyft further signals a potentially seismic shift in the global ridesharing market. Google had previously invested $363 million into Uber in 2013 at a time when Uber was approximately 8x larger than Lyft. Fast forward to October 2017, and Lyft commands approximately 35% of the U.S. ridesharing market.

3. Autonomous Vehicles

A third key trend is the convergence of ridesharing with autonomous vehicles. While projections on the pace of autonomous vehicle adoption vary, Lyft founder John Zimmer offered a helpful analogy in a recent blog post:

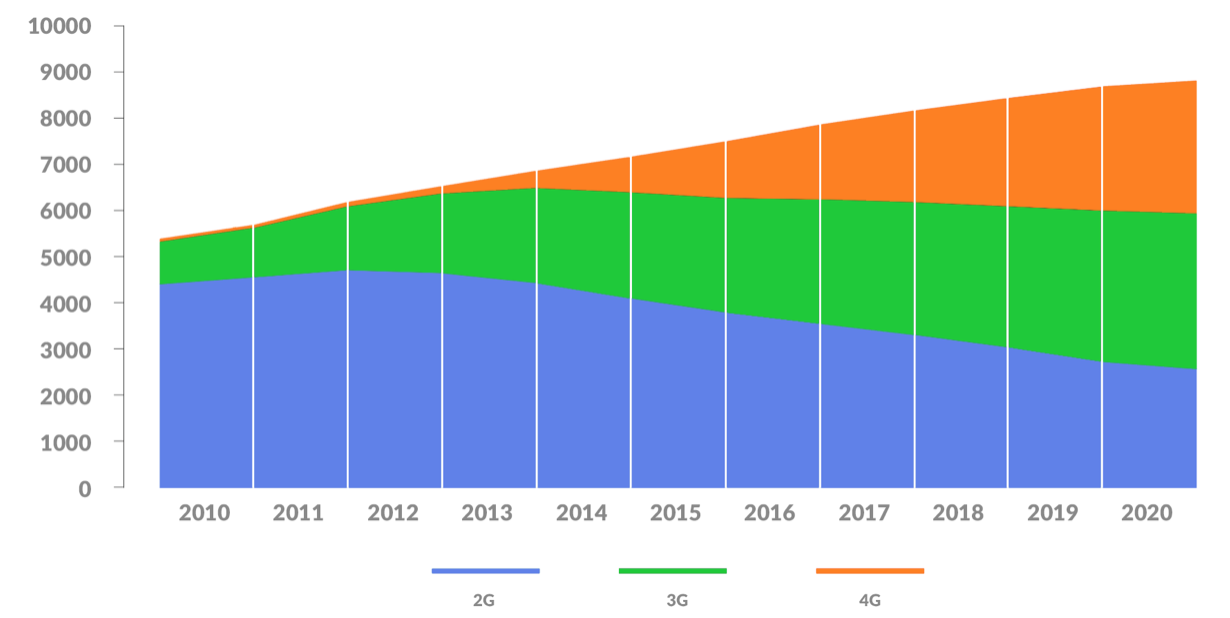

Remember when cell phone coverage transitioned from 3G to 4G? The 4G networks were slowly rolled out, first covering only the largest cities and eventually growing to cover larger and larger portions of suburban areas. This ensures that people are always covered, one way or another. If you spend most of your time in a place that’s only covered by 3G or even 2G, you still have a network to rely on. But as soon as you step into a spot with 4G coverage, you automatically get to try it. Just wait for the upcoming launch of 5G. Future 5G networks won’t be introduced to the world by new companies, they will be rolled out on top of the largest existing networks around the world.

The introduction of autonomous vehicles will follow the same pattern, until its the backbone of mobility.

As it has increasingly become clear that self-driving cars are within our grasp, everyone it taking notice.

For automakers, it’s a matter of survival. The combination of ubiquitous ride-sharing platforms with self-driving cars calls into question the need to buy a car. It’s why you’ve seen GM invest $500 million in Lyft in a long-term partnership to deploy a network of autonomous vehicles. Ford has announced that it will create a fleet of self-driving cars by 2021 in a shared network. Tesla’s cars are already outfitted with “Autopilot.” The list goes on.

For technology companies like Alphabet (Google), Baidu, Microsoft, and Apple, cars could be the next great computing platform. Baidu has partnered with the chipmaker nVidia to create an autonomous driving and navigation platform for use by third parties in 2018.

70485.png)

Ride-sharing platforms are the third leg of the stool. Interestingly, despite high-profile announcements and partnerships from Uber and Lyft, the lesser known nuTonomy was the first to get a network of on-demand, self-driving vehicles on the road.

In September 2016, the four-year-old MIT spinout launched a taxi fleet in Singapore’s One North district, and later partnered with Grab to offer self-driving rides in the entire city. Over the past year, nuTonomy has piloted deployments in the United Kingdom and United States (including a partnership with Lyft).

This week automotive supplier Delphi acquired nuTonomy for $450 million.

WHAT’S NEXT: BIKE-SHARING

Bike-sharing services are not a novel concept and have been in existence in major metropolitan areas for the past decade. But just as Uber lapped Carey Limousine, an emerging group of bike-sharing startups are achieving massive scale — and serious investors.

These companies are capitalizing on apps that enable users to easily locate, unlock, use and return bikes with the touch of a finger.

Today, bike-sharing is the fastest growing segment of the Sharing Economy, with over $1.9 billion of capital raised in 2017 alone… by two companies… in China… Mobike and Ofo. In June, Mobike raised $600 million from Tencent, Sequoia Capital, TPG, and Hillhouse.

Not to be outdone, Ofo raised $700 million from Alibaba, DST Hony Capital, CITIC and Didi Chuxing less than a month later. The companies are reportedly valued at $3 billion apiece.

Its not a surprise that Shanghai-based Mobike and Beijing-based Ofo are early leaders in bike-sharing. Mobike currently records over 25 million rides daily. Ofo tops 20 million.

What differs between the two services comes down to the experience. Mobikes are considered to be higher-end “vehicles,” costing $440 to build. They have built-in GPS trackers, look like they belong in a SoulCycle class, and cost two yuan an hour to rent.

Ofo’s bikes feel much cheaper, because, well, at $35 to build, they are. With no added bells and whistles, Ofo’s bikes rent for half the price.

Across the pond, California based LimeBike’s bright green bikes are flooding the streets of the United States. Founded in 2017, LimeBike has raised $62 million at a $225 million valuation from investors including Andreessen Horowitz, DCM Ventures, GGV, IDG, and Coatue.

Officially launched on the University of North Carolina-Greenboro’s campus, the company now operates in a dozen markets — ranging from large metropolitan cities like Seattle and Washington D.C. to college campuses such as Arkansas State University.