Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

We did a lot of things that seemed crazy at the time. Many of those crazy things now have over a billion users, like Google Maps, YouTube, Chrome, and Android.

— Larry Page, CEO, Alphabet

A brand is a promise. Accordingly, great brands are created by consistently delivering a product, service, or experience that confirms that promise. It’s reality. It’s the truth.

Starbucks has built an $85+ billion coffee empire by delivering affordable luxury in a consistent yet comfortable setting. It’s one of the reasons you will never see a franchised store — too much brand risk. Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz once said that franchising was worse than a terminal disease.

Apple is the most valuable company in the world because its brand represents beautifully designed, easy-to-use technology. The Apple logo is still a status symbol that people proudly display — not coincidentally — in places like Starbucks.

Google is among a pantheon of great brands that have become verbs — which is why many were shocked to learn in August 2015 that the company was changing its name to Alphabet. But the name change punctuated a transformation 15 years in the making. Google, once a search engine, has become a platform of assets — from Android, the largest mobile operating system to YouTube, a disruptive media platform with 1.5 billion users, and Waymo, a pioneering developer of self-driving cars. The list goes on.

In a blog post announcing Google’s new shingle, CEO Larry Page wrote, “We’ve long believed that over time companies tend to get comfortable doing the same thing, just making incremental changes. But in the technology industry, where revolutionary ideas drive the next big growth areas, you need to be a bit uncomfortable to stay relevant.”

An alphabet is a collection of letters that represent language. Alphabet, accordingly, is a collection of companies that represent the many bets Larry Page is making to ensure his platform is built to not only survive, but to thrive in a future defined by accelerating digital disruption. It’s an “Alpha” bet on a diversified platform of assets.

If you look closely, the world’s top technology companies are making similar bets.

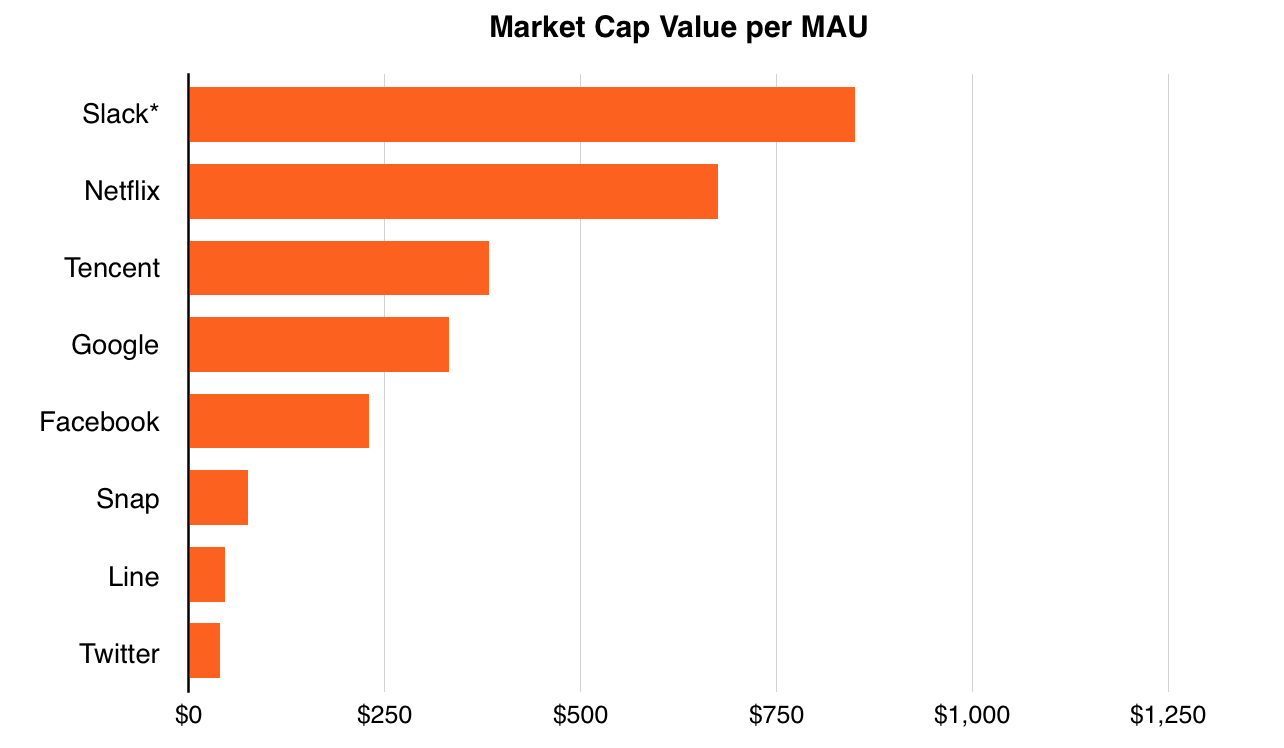

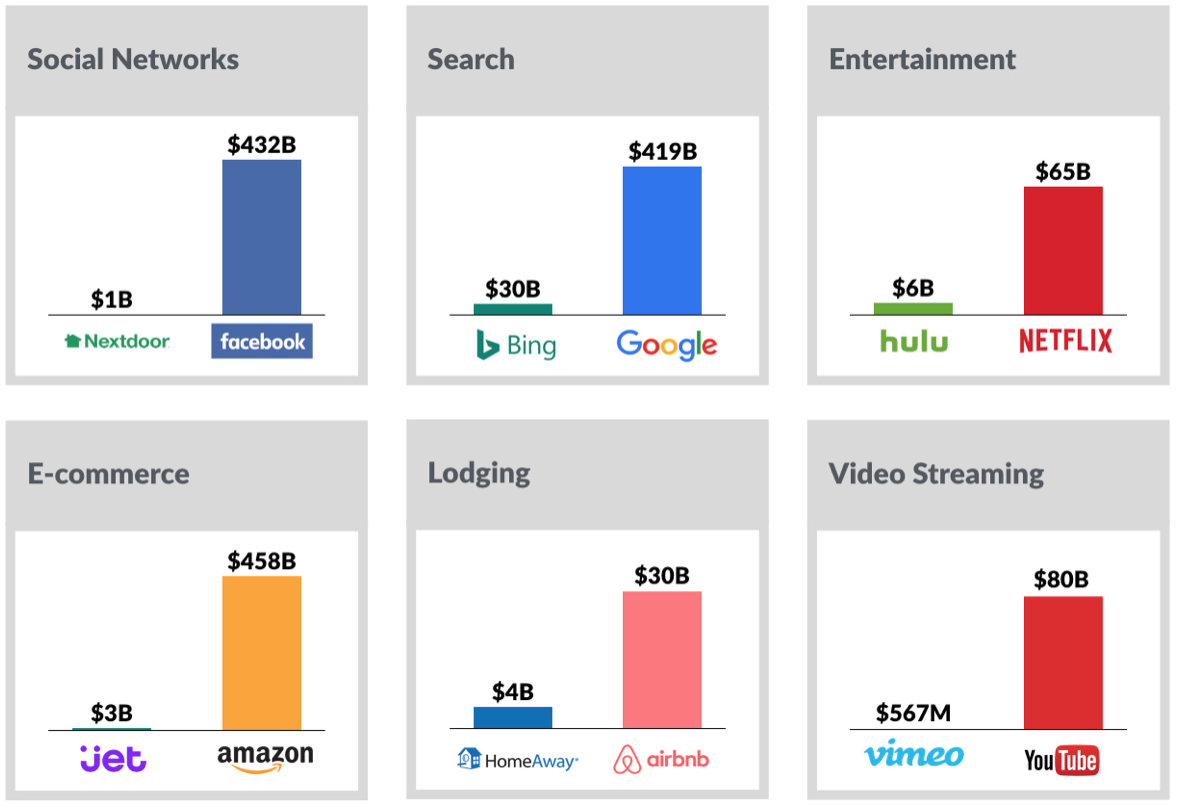

Technology in general and the Internet in particular is all about disproportionate gains to the leader in a category. Accordingly, as technology leaders like Facebook, Alphabet, and Amazon survey the competitive landscape, they have increasingly aimed to develop and acquire emerging technology capabilities across a broad range of complementary categories.

Facebook, effectively a desktop application when it went public in 2012, has completely reinvented itself into a powerful platform of mobile apps. It has built a monster network of nearly two billion people thanks to high risk venture bets on Instagram and WhatsApp. Instagram now has over 700 million daily active users, including 250 million daily Instagram Stories users. WhatsApp has over 1 billion users and 100 million voice calls are made on WhatsApp daily.

Applying the same mindset to Augmented and Virtual Reality (AR/VR), Facebook purchased Oculus for $2 billion in 2014. At the time, Mark Zuckerberg observed, “Every 10 to 15 years a new major computing platform arrives — we see that virtual and augmented reality are imports parts of this upcoming next platform.”

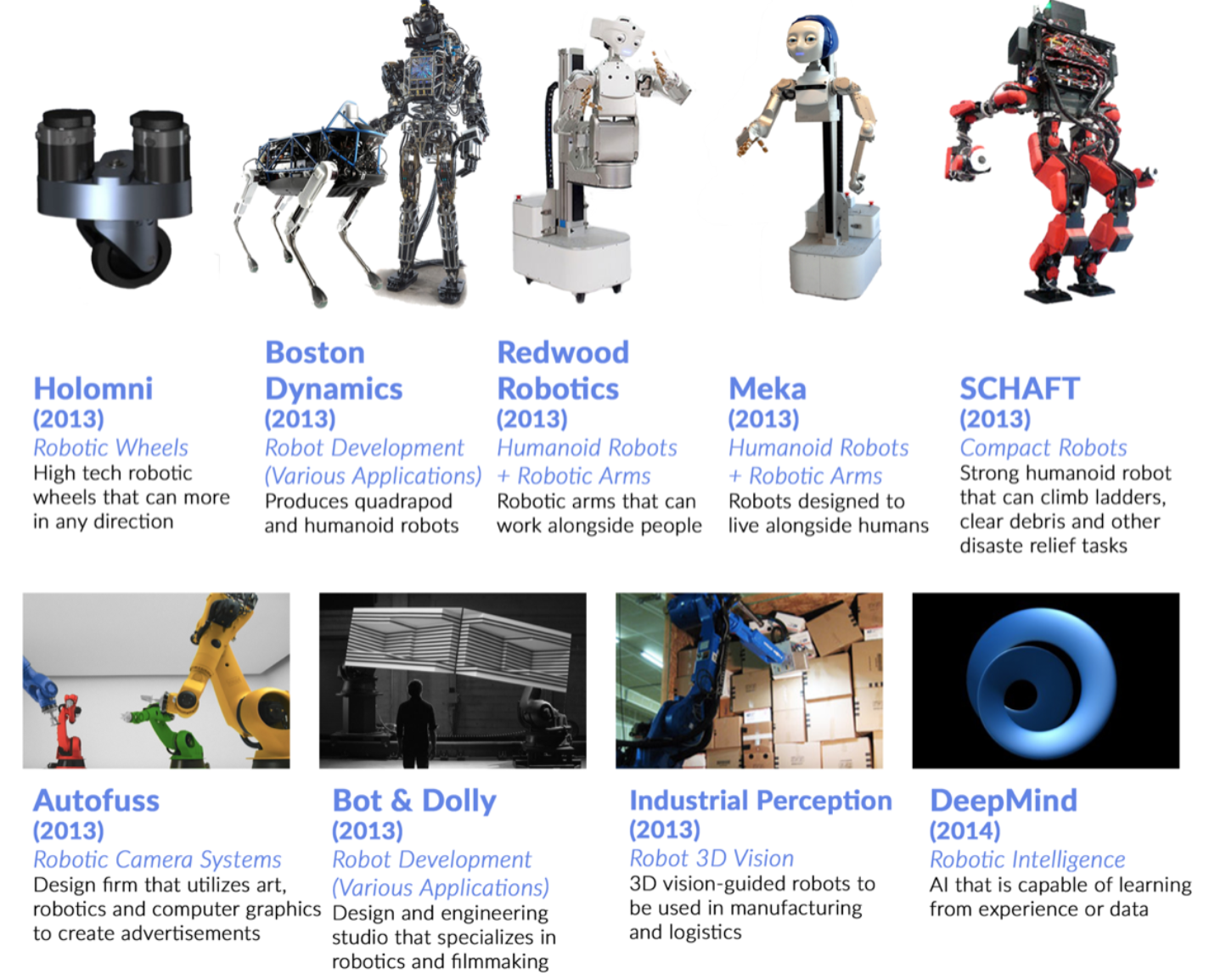

In just over a year, Alphabet kickstarted the creation of a robotics innovation arm, acquiring eight promising startups beginning in 2013. While the company has kept its plans close to the vest, the new technologies could be applied to everything from self-driving cars, to a much broader array of autonomous systems — including warehouse work, package delivery, and even elderly care.

Amazon launched in 1994, offering a novel way to purchase books while helping retailers like Target fulfill their fledgling online orders. Today it’s the dominant platform in global e-commerce. But in recent years, much of Amazon’s growth has been fueled by its pioneering cloud infrastructure services business, Amazon AWS.

What began as an internal digital infrastructure investment, Bezos productized AWS in 2004. Today it’s a $12 billion business with 40% market share, greater than the next three competitors combined — Microsoft, Google, and IBM. Analysts have recently extrapolated a $190 billion market value for AWS, which would rank it as the 30th largest business in the world.

KEY AREAS OF PLATFORM ACTIVITY

1. Autonomous Vehicles + Drones

In 2004, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched a Grand Challenge series, a multimillion-dollar competition for university robotics teams to design autonomous vehicles. A rivalry quickly developed between Stanford and Carnegie Mellon (the schools traded the top spots in the first two years of the competition) that shaped the early future of self-driving cars.

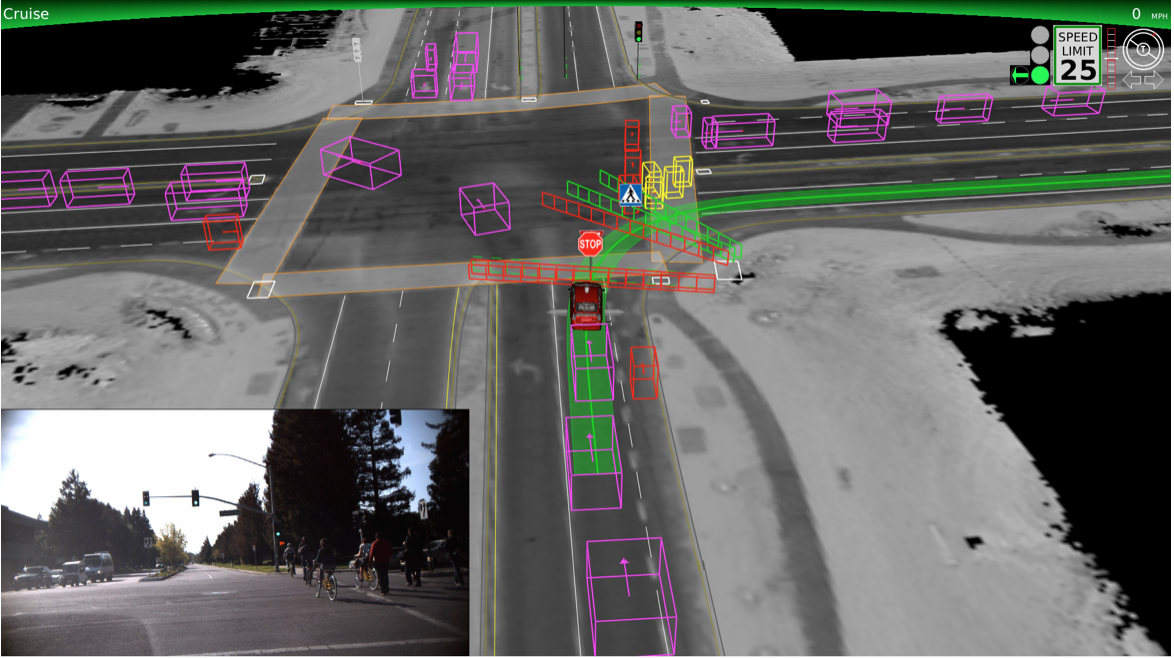

Sebastian Thrun, the leader of Stanford’s winning team, took a leave from the university in 2007 to work on Google Street View, and later founded the company’s self-driving-car project. Alphabet’s (Google) highly publicized self-driving car initiative served as a starting gun for the entire industry because it leapfrogged incremental ideas. As opposed to focusing on assisted driving, the company instead committed to creating a car without a steering wheel or pedals. It was the stuff of science fiction and it captured the World’s imagination.

As it has increasingly become clear that self-driving cars are within our grasp, everyone is taking notice.

For automakers, it’s a matter of survival. The combination of ubiquitous ride-sharing platforms with self-driving cars calls into question the need to buy a car. It’s why you’ve seen GM invest $500 million in Lyft in a long-term partnership to deploy a network of autonomous vehicles. Ford has announced that it will create a fleet of self-driving cars by 2021 in a shared network. Tesla’s cars are already outfitted with “Autopilot.” The list goes on. (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Lyft)

For technology companies like Alphabet (Google), Baidu, Microsoft, and Apple, cars could be the next great computing platform. Alphabet spun out its self-driving car project into a new company, creating Waymo in December 2016. Since 2009, Google and Waymo’s cars have spent the equivalent of over 300 years driving in simulations and live demonstrations, with about 2.3 million miles driven on real roads.

While Apple scaled back “Project Titan”, its autonomous car initiative, Tim Cook recently announced the company’s renewed focus on autonomous systems, prioritizing the development of the underlying technology for self-driving cars. In June 2017 Cook called this the “mother of all AI projects” on Bloomberg Television.

Microsoft announced an agreement with Renault-Nissan in January 2017 to develop core technology for the company’s autonomous vehicles. Renault-Nissan becomes the first customer for Microsoft’s “Connected Vehicle Platform,” which provides carmakers with a set of apps built around Microsoft Azure’s cloud, Microsoft Office, and Cortana.

Baidu has partnered with the chipmaker nVidia to create an autonomous driving and navigation platform for use by third parties in 2018.

While robots on wheels are taking to the highways, flying robots, or Drones, are lifting off faster than most predicted. In 2010, the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) estimated that by 2020, there would be 15,000 consumer drones in the country. Today, that’s fewer than the number of drones sold per month. The Consumer Electronics Association (CEA) estimates that over three million drones were purchased in 2016.

In 2014, Google acquired Titan Aerospace, a maker of high-altitude, solar-powered drones, with the idea to beam internet access from the sky to get more people connected. In January 2017, Google shuttered Titan and shifted the focus Titan’s team to other GoogleX projects, including Loon and Project Wing, the latter of which is building an automated delivery aircraft.

Facebook, which lost out to Google to purchase Titan Aerospace, bought a company that created the Aquila glider. Like Google, Facebook has sought to use the drone to increase internet access in remote areas as part of its internet.org initiative. Facebook has faced its setbacks as well, with an Aquila drone crashing on a test flight June 2016.

In December 2016, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos announced that the company had completed its first fully-autonomous drone delivery in the sleep countryside town of Cambridgeshire, England. A customer ordered an Amazon Fire streaming device and a bag of popcorn and found the goods at his doorstep 13 minutes later. A flurry of patent activity around drones signal major bets are underway.

2. Digital Assistants & Connected Home

The Internet of Things is effectively a catch-all for connecting devices — from consumer objects to industrial equipment — onto a network. This enables information gathering and remote device management via software to increase efficiency. It also enables the creation of new services, to achieve, health, safety, business, or environmental benefits. But increasingly, anything than can be connected will be connected. Accordingly, we’re poised to see a rapid proliferation of IoT devices. Today, Cisco estimates that there are 18 billion such devices, growing to 50 billion by 2020.

Google’s (Alphabet) $3.2 billion acquisition of Nest, the smart thermostat maker, in 2014 signaled the beginning of a land grab for the connected home. Later that year, it bought Dropcam, a home security camera maker, for $550 million.

As the Economist has reported, Nest has undoubtably been a disappointment to date for Google. It sold just 1.3 million units in 2015, and only 2.5 million in total over the past few years. Nest founder Tony Fadell stepped down in June 2016 amid reports that he had a much broader and aggressive vision for the product than Google was willing to pursue.

Nest’s problems are symptomatic of IoT for the home more broadly. According to Forrester, only 6% of American households have a “smart” home device, including internet-connected appliances, home-monitoring systems, speakers or lighting. But as isolated offerings evolve into integrated, compelling services, the opportunity is open-ended. Major technology companies have taken notice, rolling out a variety of offerings to network key aspects of your home.

Last December, Wynn Resorts announced that it would install an Amazon Echo in each of the 4,748 rooms of its flagship Las Vegas property. Beginning in this Summer, the voice activated smart speaker powered by the digital assistant, “Alexa”, will enable guests to control the lights, television, room temperature, drapery, and other amenities. As CEO Steve Wynn observed, “[Alexa] becomes our butler, at the service of each of our guests.”

Applying this technology to conversational speech recognition led to the launch of Apple’s Siri in 2011— the first broadly distributed advanced consumer digital assistant. A year later, Alphabet (Google) launched Google Now.

But it’s Amazon’s Alexa — which wasn’t released until 2014 — that is becoming the face of digital assistants. Why?

Ironically, Amazon is winning with hardware. Unlike Siri, which resides in a crowded field of iPhone apps, or Google Now, which is embedded in Android applications like “Search”, Alexa was launched as the flagship feature of the sleek Echo speaker. Buying an Echo was like buying a robot. It captured the public imagination, selling 4.4 million units in its first year. Amazon was projected to sell over nine million units in 2016 — it moved 9x more Echoes this Christmas than last year — and more than 40 million per year by 2020 alone. That’s a $4+ billion revenue line.

The company recently announced that Alexa has over 12,000 distinct “skills” in her toolkit — up from 1,000 in June 2016. New “features” announced include whispering and pausing for emphasis. Customers love the product so much that there have been over 250,000 marriage proposals to Alexa.

Amazon’s ambush has broader implications. As with the smartphone, we’re seeing early signs of platform wars around connected homes, with “Smart Speakers” like Echo as a gateway. You can use the device to control a variety of smart appliances and on-demand services through integrations with companies like Samsung, Philips, Belkin, and Uber. It recently released an open API framework to enable the integration and management of other devices and services.

Apple, which announced HomePod this Summer, and Alphabet, which launched Google Home in 2016, are scrambling to catch up.

Leading technology companies are also competing to build the software to connect IoT devices, creating a centralized network of devices. Apple’s HomeKit, for example, aims to connect a range of proprietary and third-party smart home devices through an integrated control panel. Amazon recently released an open API framework to enable the integration and management of other devices through its voice-controlled Echo product.

3. AR/VR

Virtual Reality (VR) had been pursued and promised since the 1950s, but the convergence of low-cost mobile hardware and powerful new software platforms is bringing it to life. In less than five years we are seeing ripple effects across digital media and beyond.

Oculus VR founder Palmer Luckey, a college dropout, created a Virtual Reality (VR) “prototype” in 2011 with a smartphone, two eyeglass lenses, duct tape, and a bucket. One year later, Luckey tried to raise $250,000 on Kickstarter and raked in $2.4 million. In 2014, Facebook bought his company for $2 billion and VR had seemingly arrived.

While Oculus may be a disappointment for Facebook to date given the nascent technology, today there’s a big belief and a lot of momentum in the idea that first Virtual Reality, and ultimately Augmented Reality, are the next major platform in computing — in the same way that the World went from mainframe to PC to client server to web to mobile. You can already see the smartest companies in the world are deploying billions of dollars of capital around making this happen.

Snapchat, in particular, has pioneered commercial Augmented Reality technology in the social media space with its “selfie lenses” that can seamlessly apply everything from puppy dog ears to flower crowns over user images seamlessly. This April, Snapchat announced a new set of features that allows users to place virtual objects in the real world using a combination of advanced camera and depth sensor applications.

This January, Google announced partnerships with Gap and BMW, deploying its AR app Tango to create virtual showrooms. With BMW, Google is developing an app that displays BMW vehicles on smartphone screens, allowing shoppers to walk around superimposed vehicles, manipulating, colors, trims, and even backdrops (e.g., home, garage, etc.) for additional context.

Amazon is rumored to be exploring digital stores to sell furniture and other home products. These stores will reportedly integrate augmented and virtual reality technology, enabling people to see how things like sofas, desks, ovens and more look in their homes before they make a purchase.

Apple officially entered the AR/VR race this Summer, announcing ARKit at WWDC. This new platform allows developers to create AR experiences for the iPhone and iPad using the device’s camera. ARKit opens up mobile AR experiences beyond Pokemon Go and immersive games, potentially bridging the technology into schools, hospitals, and retailers. Furniture retailer IKEA has already announced plans to launch an ARKit catalog for the iPhone this Fall.

WHAT’S NEXT

Blockchain

The launch of Bitcoin in 2009 marked the next frontier for open platforms. At face value, Bitcoin promises an alternative to one of the World’s quintessentially “closed” platforms — money. Instead of relying on central banks for validity and subjecting people to arcane exchange mechanisms, Bitcoin is an open, electronic, peer-to-peer currency. It’s not without controversy.

But while the future of Bitcoin is uncertain — it could be the Facebook or the MySpace of so-called “cryptocurrencies” — the underlying technology powering it, “Blockchain,” is here to stay. Effectively a decentralized, open-source public ledger for the exchange of information, blockchain has the potential to transform any industry that relies on middlemen and “honest brokers” for critical functions — from finance to supply chain management and academic credentialing.

To paraphrase Marc Andreessen, blockchain gives us, for the first time, a way for one Internet user to transfer a unique piece of digital property or information to another Internet user, such that the transfer is guaranteed to be safe and secure. Everyone knows that the transfer has taken place, and nobody can challenge the legitimacy of the transfer.

In other words, Bitcoin is just the beginning. The underlying technology can applied to all manner of “exchanges,” whether or not they’re related to money. The consequences of this breakthrough are hard to overstate. Ethereum, a non-profit that is creating a blockchain framework intended to be more flexible that the original which was created for Bitcoin, has helped evangelize the technology. Ethereum’s value has increased 4,500% this year and it is now 80% the total value of Bitcoin, poised to surpass Bitcoin’s market value in the very near future.

While leading technology platforms have yet to announce major Blockchain initiatives, it’s not hard to see where the applications of blockchain can intersect with current product offerings.

Space

Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Blue Origin are shattering the old Space cost paradigm by making rocket reusability a reality. In November 2015, Blue Origin’s New Shepard became the first rocket to stick a controlled, upright landing after a brief visit above the Space line. SpaceX’s Falcon 9 followed suit weeks later.

All told, Goldman Sachs estimates that improved rocket design and logistics have driven down launch costs 10x over the last decade — more than the entire previous history of Space exploration combined.

2689640878.jpg)

As James Crawford, the founder and CEO of satellite imaging startup Orbital Insight has observed, “In the old days, when satellites were like mainframes, incredibly expensive, if you managed to get an image, you probably spent $10,000 on them.” New satellite technology fundamentals, coupled with declining costs for computing power and data storage, have changed the paradigm.

Lower-cost satellites can now be deployed to capture enormous quantities of imaging data that can be applied across a wide range of business functions. Weather services, for example, can utilize sensors on Nanosats to gather more timely information, to the benefit of farmers, transportation and logistics businesses, and rescue workers. Government agencies can analyze imagery to monitor deforestation and environmental impact over time.

In 2014, Google purchased satellite startup Skybox Imaging for $500 million, renaming it to Terra Bella shortly afterwards. Through this acquisition, Google integrated its machine learning capabilities with Terra Bella’s satellites in orbit, with the goal to analyze images taken from space in ways that have never been done before. This year, Planet acquired Terra Bella, and as part of the deal, Alphabet will take a stake in Planet and it has agreed to purchase satellite images from the company for five years.