Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

In 2011, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen famously penned his essay “Software is Eating The World,” arguing that all companies will eventually become software companies.

Today, Silicon Valley is betting that software will eat the farm. From sensors that track soil health to drones and “nano-satellites” that gather data from the sky, entrepreneurs and corporate R&D labs alike are racing to reimagine agriculture from the ground up.

Why now? On one level it was just a matter of time. Everybody eats. McKinsey estimates that food and agriculture is a $5 trillion industry and growing.

But agriculture is also at the intersection of the world’s greatest challenges. The planet’s population is projected to rise from 7.5 billion to over 9.7 billion by 2050 and the United Nations estimates that food production will need to rise at least 70% to meet baseline demand. Globally, the agricultural sector already consumes approximately 70% of the planet’s accessible freshwater. And for the 70% of the world’s poor who live in rural areas, agriculture is the only form of employment or subsistence.

What do all these 70s add up to? A massive opportunity to be sure. But it’s also a reminder that the most impactful innovation will focus on the big challenges first. Incremental ideas wrapped in technology are unlikely to bend the curve. At the crux of the agricultural challenge and opportunity is the fact that most land suitable for farming is already farmed. Growth, in other words, must come from higher yields.

As The Economist noted in a 2016 technology quarterly focused on innovation in agriculture:

Farming has undergone yield-enhancing shifts in the past, including mechanization before the second world war and the introduction of new crop varieties and agricultural chemicals in the Green Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet yields of important crops such as rice and wheat have now stopped rising in some intensively farmed parts of the world, a phenomenon called yield plateauing.

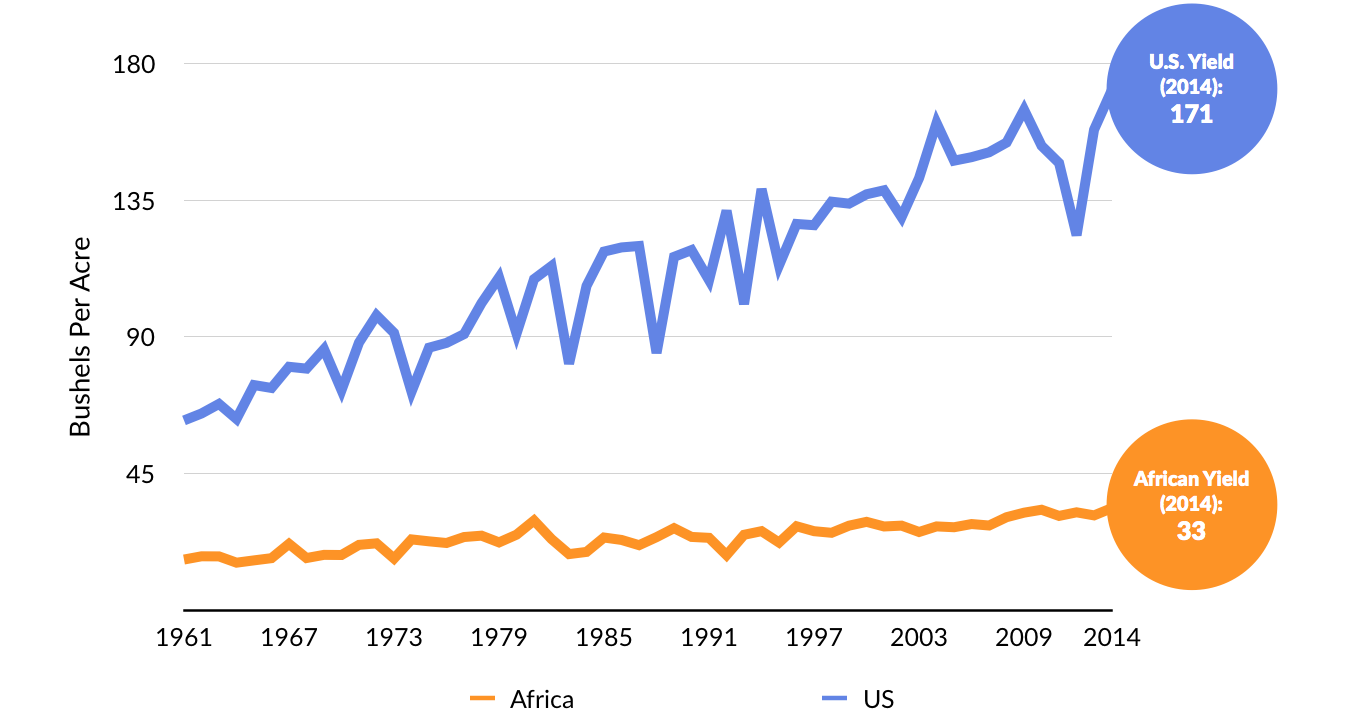

But for over one billion small farmers — particularly in the developing world — it is as if the “Green Revolution” never took place. The “Yield Gap” — the astonishing difference between developed and emerging country farm production — continues to widen.

The is one of the all-time great global arbitrage opportunities. Focused technology and business model innovation will further catalyze the transformation of agriculture. We’re on the verge of the next great Green Revolution.

SOFTWARE EATS FRUITS AND VEGETABLES?

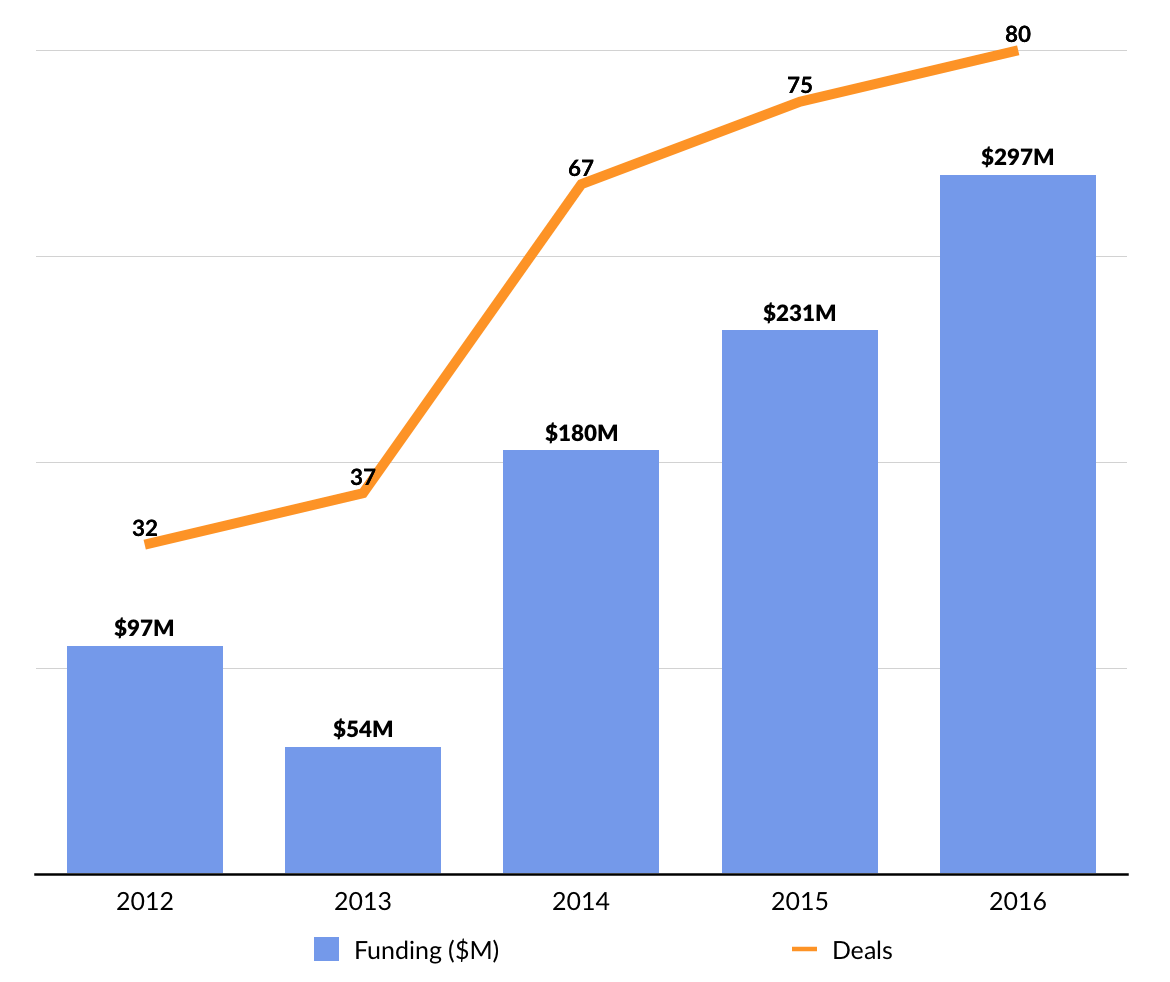

According to CB Insights, venture investments into agricultural technology, or “AgTech,” have topped $820 million across 271 deals since 2012. The Climate Corporation’s acquisition by Monsanto in November 2013 for $1.1 billion was a starting gun for a flurry of investment activity. The first quarter of 2017 was a new high water mark, with more than $105 million invested across 16 deals.

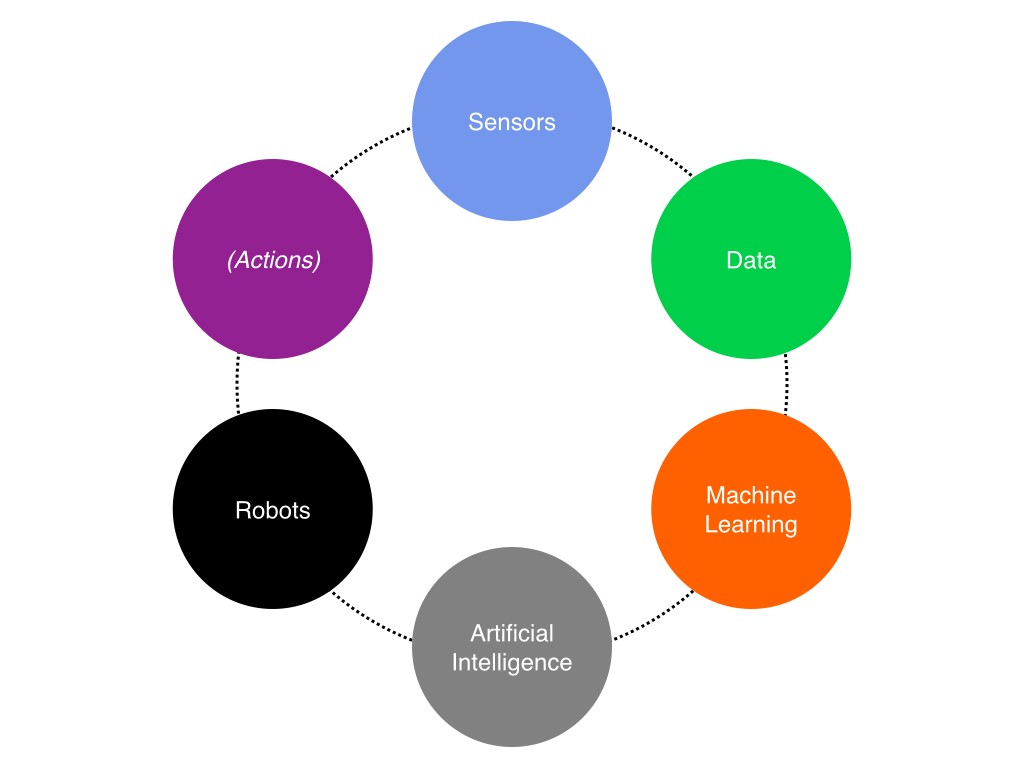

Much of the innovation and investment activity has focused on three core areas: 1) Data Analysis + Monitoring, 2) New Farming Models, and; 3) Hardware + Smart Devices (e.g. Sensors). Drones and low-cost, low-orbit “nano-satellites,” which enable aerial monitoring, are a related category. Data and imaging from these vehicles enable trends analysis, forecasting, and early warning indicators.

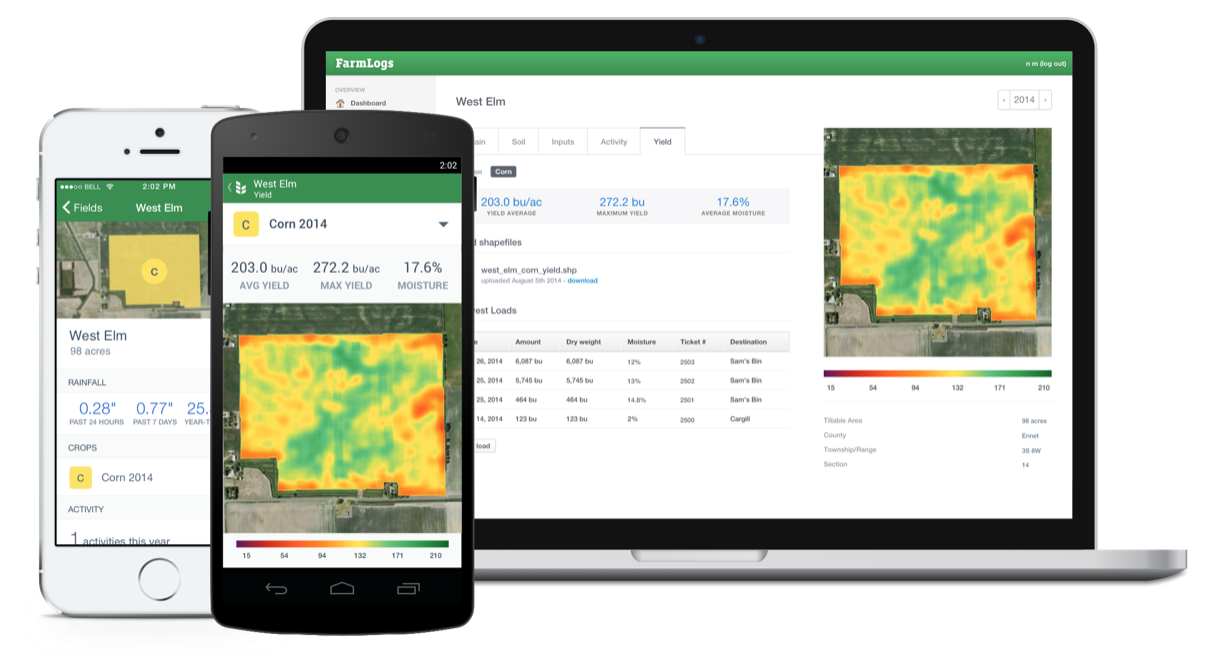

Notable emerging companies include Farmer’s Edge, which has raised $104 million from a syndicate headlined by Kleiner Perkins and Mitsui. Founded in 2005 and headquartered in Winnipeg, Canada, Farmer’s Edge has developed an integrated farm management platform that helps farmers boost crop production and improve sustainability through actionable data analysis. It currently serves growers in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Russia, and Australia. Y Combinator graduate FarmLogs, based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, has raised $37 million to build out a competitive platform. Its network of farmers, based predominantly in the United States, cultivate over 65 million acres.

As fertile cropland grows more scarce worldwide, startups are also looking to reimagine the farm completely. Founded in 2015, Bowery Farming, for example, is creating indoor farms, relying on LED lighting, robotics, and computer software to grow vegetables. Bowery is able to cultivate without pesticides and uses 95% less water than comparable farms. And its able to grow 365 days a year. The company locates its farms close to large cities to cut down transportation costs while increasing access to sustainable produce. Bowery recently raised $20 million in June 2017 from investors including Google Ventures, GGV, and General Catalyst.

This week, Parisian startup Agricool raised $9 million from investors including Daphni to grow fruits and vegetables inside containers. The company manages the temperature, humidity, chemical levels and color spectrum to optimize growth.

The most active venture investors in AgTech over the last five years include Andreessen Horowitz, Khosla Ventures, Google Ventures, Middleland Capital, and Y Combinator (YC). In January 2017, YC President Sam Altman signaled that his platform would increasingly recruit water technology startups for its accelerator programs, including those focused on smart irrigation systems and broader efficiency in agriculture.

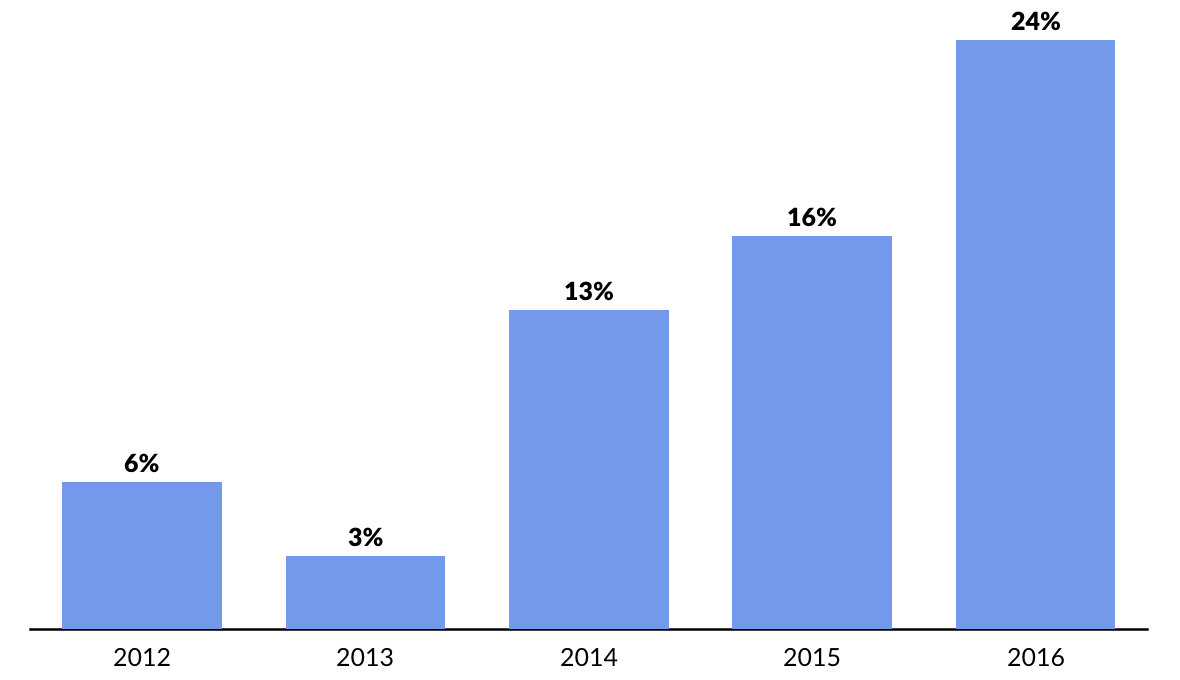

Corporate VCs have have also accelerated investments into agriculture technology startups in recent years. In 2016, 24% of AgTech deals included a corporate investor, compared to just 6% in 2012. The venture arms of agriculture giant Monsanto and chemical company BASF have been the most active, completing approximately twenty transactions apiece since 2012.

Swiss agriculture business Sygenta comes in a close third, with its venture arm completing 15+ deals since 2012. Additionally, Sygenta has acquired at least five AgTech startups since 2012 including farm management software company Ag Connections, and seed companies Sunfield Seeds, MRI Seed Zambia, and Lantmannen.

REALITY CHECK

While the future of the farm may be digital, most Silicon Valley startups are operating in the realm of proof of concept. Agricultural ecosystems are highly complex environments that cannot be mapped or understood by dropping a few sensors in the ground.

Dale Huss, a senior manager at Ocean Mist Farms — the largest grower of Artichokes in the United States — put it like this in a panel at the recent Forbes AgTech summit:

The reason that we don’t use these sensors is because the ones that we’ve used up until now are inconsistent… One of these days, there will be one that we trust, and we’ll take a look at it but this smoke and mirrors stuff and the computer diagrams and all the crap that we see out there – it doesn’t work, and we need something that works.

To understand the complexity of an agricultural ecosystem, consider the complexity of the human body. You can’t just embed a sensor to understand how it works. Advanced medical applications using emerging technology are building on generations of research from both the public and private sectors. Agriculture has historically received a fraction of the attention.

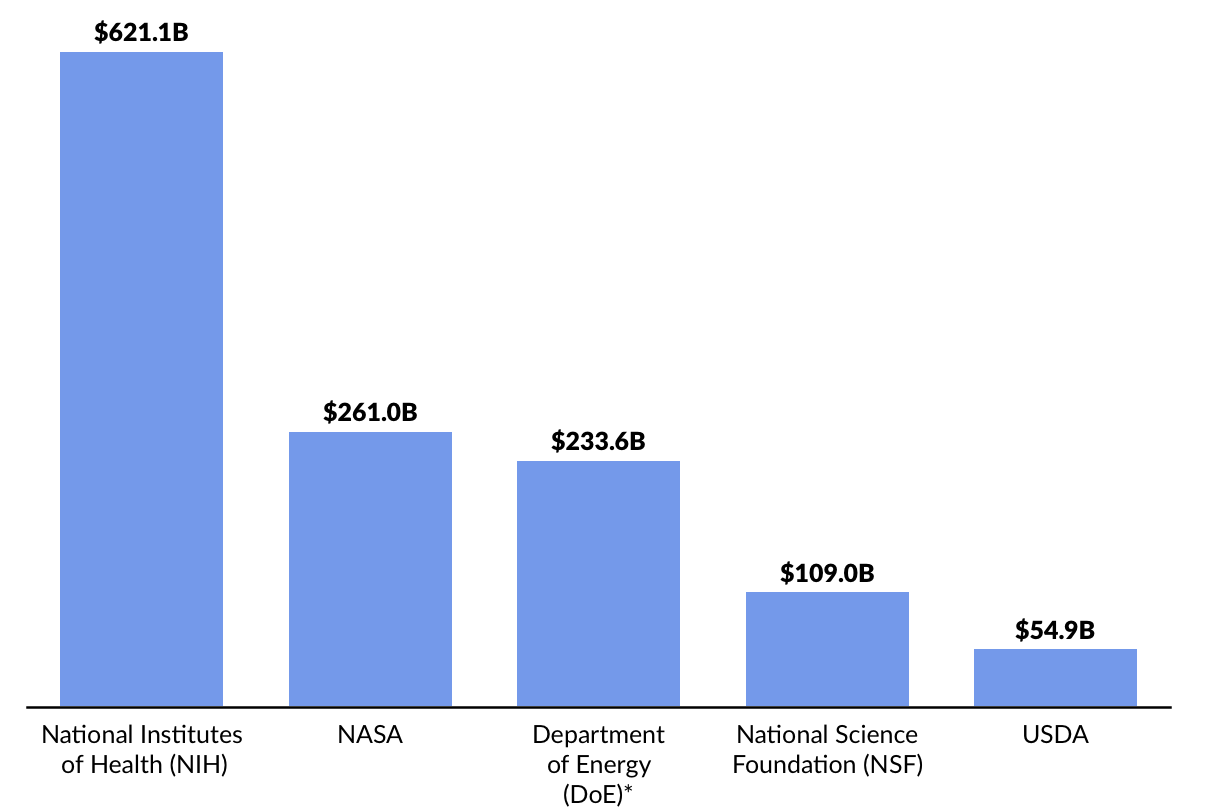

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), for example, has grown to become the largest single public funder of biomedical research in the World. Over $600 billion of Federal dollars have been allocated to the NIH R&D over the past twenty years — about the same amount as NASA, the Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) combined.

Source: NIH, Department of Energy, NASA, NSF, USDA

*Funding amount allocated towards “Science and Energy” at the Department of Energy

Federally funded NIH research has produced staggering gains. The NIH’s Human Genome Project alone has resulted in an estimated $1 trillion of economic growth. NIH funded research has also led to the development of the first cancer drug, cochlear (ear) implants, and meningitis and childhood vaccines that have saved tens of millions of lives.

Agriculture R&D has largely been stagnant, and as a result, it’s at least a generation behind human biotechnology.

It also doesn’t help that corporate agricultural R&D budgets have been allocated more towards “developing” incremental improvements to the same old solutions rather than “researching” game-changing new ideas.

Monsanto developed their genetically modified seeds twenty years ago, reshaping the farming industry. Since then, the agriculture giant has mainly been on cruise control, churning out incrementally better seed varieties to increase top line revenues. Other big companies are taking a similar approach, focusing on increasing earnings as opposed to allocating resources towards finding the next groundbreaking agriculture product.

A related challenge has been that most of the new Ag Tech startups are focused on advanced technologies that could only be plausibly adopted in the developed world, due to prohibitive costs, technology complexity, or both. But this won’t help close the yield gap, the area of the largest opportunity.

MIND THE GAP

To mind the gap, we believe that innovations in three key areas will lead to exponential benefits to farms worldwide.

1. Water Efficiency

To survive in a desert, the last thing you’d think to do is pour water into the sand. Yet, that’s exactly what farmers in California are doing where droughts have long since become the new normal. Almonds, one of California’s largest, and thirstiest, cash crops, consume approximately one gallon of water for every nut produced. That translates to 10% of California’s agricultural water supply per year.

Water efficiency — from planting the right crops in the right place to adopting technologies that reduce water waste — is an immediate imperative. Agriculture already consumes approximately 70% of the world’s reachable fresh water supply. Increasing farming output to reach accelerating demand in a world where an estimated 2.7 billion already live in a state of constant water shortage will be impossible without an emphasis on improvements in water efficiency.

Water data platforms such as WaterSmart, Utilis, CropX, Valor Water and Pluto AI, are helping farmers, homes and businesses better analyze and optimize their water usage. We expect to see acceleration innovation and investment activity in this space.

mOasis, based in the Bay Area, is pushing the envelope with a soil polymer that helps farmers reduce water usage without sacrificing production. Just the size of a single grain of sand, a mOasis polymer can soak up to 250 times its weight in water and release it into the soil. According to the company, the use of this hydrogel could lead to higher crop production while reducing water usage up to 20%.

2. Soil Science

The Fertile Crescent was once home to some of the earliest human civilizations, the same civilizations that invented the wheel, developed writing, and built the foundations of mathematics and astronomy. It flourished in many parts thanks to superior soil quality, which led to the development of modern day agriculture.

While often ignored as just dirt beneath our feet, the soil is a complex ecosystem of bacteria, fungi, and minerals that has a direct impact on the health of crops and plants. If healthy soil has led to the creation of human civilizations, unhealthy soil has led to the demise of others. In fact, it has been argued that the Mayan Civilization fell mainly due to soil runoff and erosion.

As Trace Genomics cofounder Poornima Parameswaran stated in an interview, “Think of soil as the immune system for crops.” Borrowing a page out of 23andMe’s book, Trace Genomics analyzes soil samples, tests the sample for organisms like bacteria, viruses and fungi, and returns a “health report” to guide interventions.

TPG backed Inocucor develops sustainable biological products with the goal of improving soil health, and by extension, crop yields. Synergro, the company’s flagship product, is a formula of live bacteria, yeast, and fungi, designed to work symbiotically with existing soil microbiomes. The company has shown early promising results in stimulating plants to their full yield potential while improving fundamental indicators of soil health.

3. Biomaterials

While chemical pesticides have protected farms from harmful weeds and bugs, they also result in serious health risks in both humans and the environment. Chemical pesticides have been linked to increased risk of cancer, Alzheimer’s Disease, ADHD and even birth defects. Pesticides also strip fertile farm lands of valuable nutrients and microbes and leech into groundwater, contaminating fresh water supplies.

We’re seeing a growing number of startups focused on biological and organic solutions to chemical pesticides. Indigo Agriculture, for example, uses plant microbiomes and bacteria to strengthen plants against disease and drought. Khosla-backed BioConsortia and NewLeaf Symbiotics are tackling the same problem by developing naturally proliferating, microbial alternatives to synthetic fertilizers. Marrone Bio Innovations is working on a biological alternative to chemical pesticides and has developed four biopesticide products for use against insects, fungi and weeds.

Furthermore, labs are working on a variety of moonshot organic defense mechanisms against weeds and bugs. Researchers, for example, have created genetically enhanced male Diamondback Moths that kill female larvae, sabotaging reproduction of the pests, which damages upwards of $5 billion of crops annually worldwide.

Still in the early days, the search for biological alternatives to chemical products faces challenges due to a lack of understanding of soil biomes and microbes. While corporations have spent decades synthesizing and understanding how chemicals affect plants, soil and humans, the study of soil microbes is relatively nascent.

WHAT’S NEXT

While the next Green Revolution represents a massive opportunity, the greatest gains are likely to occur at the intersection of technologies and practices that can reduce the yield gap, applied thoughtfully in places where the needs are most acute.

In this case, the recently-launched Shared X offers an important window to the future. Founded by former Kleiner Perkins partner John Denniston and Tony Salas, the former Head of the Peruvian Agriculture R&D Institute, Shared X is growing high-value specialty crops on farms in emerging countries. It deploys advanced, sustainable cultivation techniques to close the agricultural yield gap, and then openly shares them with neighbors.

Today, Shared X has little need for the latest sensor technology or digital farm management platforms. It is focusing on the first things first — applying proven, sustainable farming techniques in areas that have yet to adopt them. And in the process, it is generating a powerful social impact in the communities around its farms by lifting smallholder farmers out of poverty.