Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

In the 1950s the world’s working ports looked a lot like they did in centuries past. Ships docked. Armies of longshoremen descended to unload cargo of all shapes and sizes crammed into the hold. Then they scrambled to squeeze in outbound cargo in a game of “maritime Tetris.”

The process was inefficient and expensive. Most ships spent more time tied up than in transit. And cargo had a way of mysteriously vanishing — especially whiskey. It wasn’t unusual for a third of a Scotch shipment to be lost to “breakage.”

But in 1937 an American trucking magnate named Malcom McLean had an idea that changed everything. He wagered that sorting and packing goods into uniform containers for shipment would make the process faster, safer and cheaper. Standard cargo units would make it more efficient to load ships, and they could be moved more quickly from truck, to train, to ship.

Twenty years later, McLean’s prototype container ship — a converted World War II tanker named Ideal X — sailed from the port of Newark, New Jersey to Houston, Texas with 58 containers on specially rigged decks. He calculated that it cost $0.16 per ton to load, compared with $5.83 per ton for loose cargo on a standard ship. “Containerization” was born. By 1983, 90% of countries had developed container ports.

Containerization was more than a cost saver. It was a catalyst for global commerce. And as The Economist notes in “The humble Hero:” In 1965 dock labor could move only 1.7 tons per hour onto a cargo ship. Five years later a container crew could load 30 tons per hour. This allowed freight companies to use bigger ships while simultaneously slashing the time spent in port. The average cargo journey time fell by half.

Ports became bigger and their number smaller. More types of goods could be traded economically. Speed and reliability of shipping enabled just-in-time production, which in turn allowed firms to grow leaner and more responsive to markets as even distant suppliers could now provide wares quickly and on schedule. International supply chains also grew more intricate and inclusive. This helped accelerate industrialization in emerging economies such as China

— The Economist, “The Humble Hero”

Today, the global shipping and logistics industry is poised for a new wave of transformation as rapidly changing technology fundamentals and business models are creating opportunities “beyond the box.”

STATE OF PLAY

In a 2011 essay titled “Software is Eating The World,” Marc Andreessen argued that all companies, regardless of industry, will be eventually become “software” companies. The shipping, and logistics industry — a fragmented collection of service providers that has largely resisted technology innovation to date — is poised for a digital transformation.

Powerful new software platforms, data applications, and business models are streamlining how goods are shipped, tracked, and ultimately delivered to the consumer’s doorstep. Byzantine networks of intermediaries, legacy processes, and logistical obstacles are making way for streamlined, transparent services.

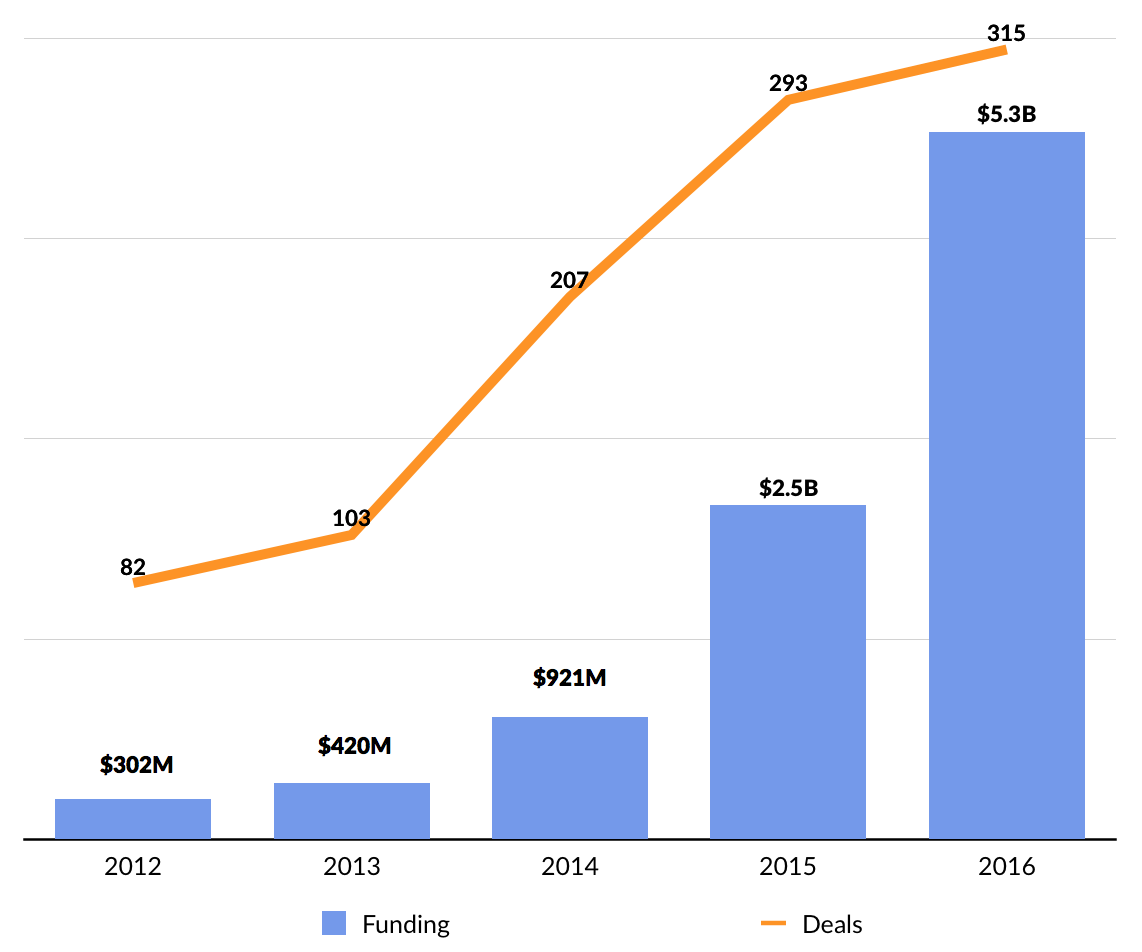

Venture Capital investment activity in shipping and logistics technology startups has been accelerating since 2014, with annual funding more than doubling per year. According to CB Insights, over $10 billion has been invested in this period across more than 1,000 deals.

A flurry of companies have launched with the aim of tackling inefficiencies across the supply chain. They primarily fall into three categories: Supply Chain Infrastructure, Freight Logistics, and Sensors + IoT. Two of the most well funded companies in the space are Infor and Alibaba-spinout Cainiao. They have raised $2.5 billion and $1.5 billion respectively to provide to provide e-commerce and supply chain logistics management services for companies that aren’t Amazon and Alibaba. San Jose-based Alien Technology has raised $455 million to create RFID sensors for manufacturers to tag and track cargo.

SV Angel, FundersClub, Kleiner Perkins, and NEA have been the most active venture investors in shipping and logistics startups over the last five years. Among strategic investors, UPS and FedEx have been the most active, accounting for nearly half of the deals done by major corporate investors in the space. UPS has focused its 20+ investments and acquisitions across the spectrum — from drones to e-commerce and trucking. Unlike UPS, FedEx’s deals have been mostly acquisitions, primarily focused on the third-party logistics and warehousing capabilities.

SMARTER GLOBAL FREIGHT

Today, 12% of Global GDP is allocated to logistics expenses and companies around the world spend $1.1 trillion on freight forwarding alone.

The concept of freight forwarding is simple. Any shipment weighing over 150 kilos is considered freight and getting it from origin to destination requires multiple handoffs on the land, sea or air. To optimize this process, freight forwarders provide the brokering services to get wholesale and retail customers the best shipping rates, owning relationships with truckers and shippers. Unfortunately, the hand off is done through people via phone calls, fax messages, and worse off, paper.

While technology innovation feels more and more like the Jetsons, freight forwarding looks a lot more like the Flintstones. The average age of the ten most valuable freight logistics companies is over 100-years-old. All of the key legacy players were founded well before the Internet Age and have built behemoths that rely on man power and technology-lite processes.

Source: S&P Capital IQ, GSV Asset Management

*Norfolk Southern was formed following a merger of Southern Railway and Norfolk & Western Railway, founded in 1894 and 1870 respectively.

Companies like Flexport are developing a digitized freight forwarding industry, effectively creating an operating system for global trade.

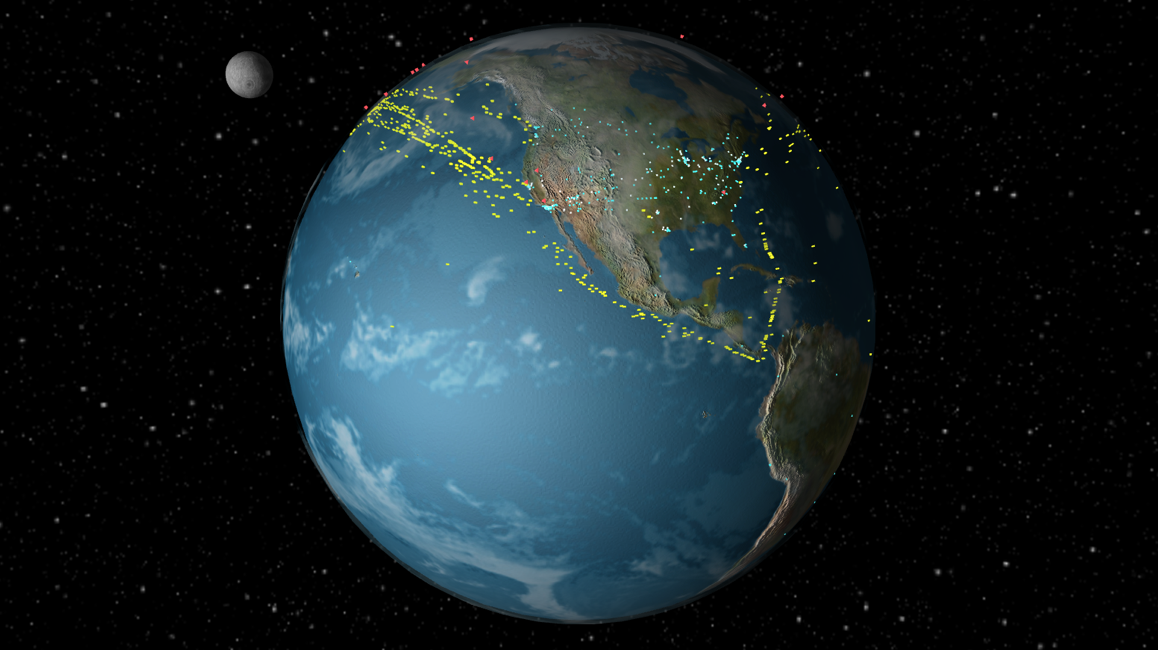

Companies go to Flexport to move freight from point A to point B, with specific rules and qualifications. Flexport then uses its software, built on a global database of shippers, to analyze all routes, rates, speeds and customs compliance requirements to determine the most optimal route for the shipment. It then digitally brokers the legs of the shipment with handlers and sends the shipment to its final location, providing tracking services every step of the way.

Source: Flexport

What Flexport is ultimately doing is providing transparency to an industry that is typically a giant black box, an issue that Flexport CEO Ryan Petersen experienced first hand when he began his career by buying and selling goods from China. And by using digital technology and improving algorithms, Flexport’s routing decisions will be increasingly automated and smarter as more transaction data is captured. Founded in 2013, Flexport has raised $94 million from investors including Founders Fund, Bloomberg Beta, Felicis Ventures, and First Round Capital.

LOGISTICS AS A SERVICE

Today, over 70% of consumers buy products online. Forbes estimates that the e-commerce industry will surpass $2 trillion this year, and eMarketer projects that it will surpass $4 trillion by 2020. The rise of e-commerce has created the opportunity for companies to provide shipping and “logistics-as-a-service” to smaller companies. Amazon and Alibaba are using their massive networks and balance sheets to seize the opportunity.

Alibaba-owned Cainiao Logistics was launched to meet the logistics demands of China’s online and mobile commerce sector. China is the world’s leading e-commerce market with huge projected growth, thanks to the rise and success of e-commerce giant Alibaba and its sister properties. Analysts estimate that by 2018, over 40% of China’s population will shop online, doubling online retail sales to exceed over $1 trillion.

Cainiao’s has developed a delivery and warehouse network that primarily focuses on serving merchants on Alibaba’s marketplaces. Its platform provides sellers with the physical and technical infrastructure to transport goods from point A to point B, while also improving visibility and efficiency in all parts of the supply chain — from buyer, to shipper to seller. The company has raised over $1.5 billion and currently supports 152 countries and 70 carriers.

Companies like Convoy and Shyp digitizing and modernizing the domestic the shipping and handling industry. Convoy provides an on-demand trucking service for regional and local shipments. Its platform connects shippers with nearby trucking companies to help them book jobs on short notice using a “load matching” algorithm. Its marketplace improves efficiency in the domestic transport industry while also providing an unprecedented layer of transparency across the shipping lifecycle.

Other startups are building a software layer for e-commerce management. Salesforce-backed Infor has developed an enterprise CRM for supply chain management. Elementum offers a suite of mobile apps that enable supply chain monitoring services to retailers. Narvar bridges the gap between retailer and shopper by creating a delightful post-purchase experience.

AMAZON EATS THE WORLD

Amazon was launched in 1994 — the same year Marc Andreessen co-founded Netscape, effectively creating the Internet as we know it. Amazon started as a novel way to order books and it helped retailers like Target fulfill their fledgling online orders. At the time, Sears, once the largest retailer in the world, had a $16 billion market value. Today, Sears is worth $1 billion and it recently announced that it may have to file for bankruptcy to protect itself from creditors. Amazon is now worth over $450 billion.

Source: Yahoo Finance

*Peak Market Value 2006

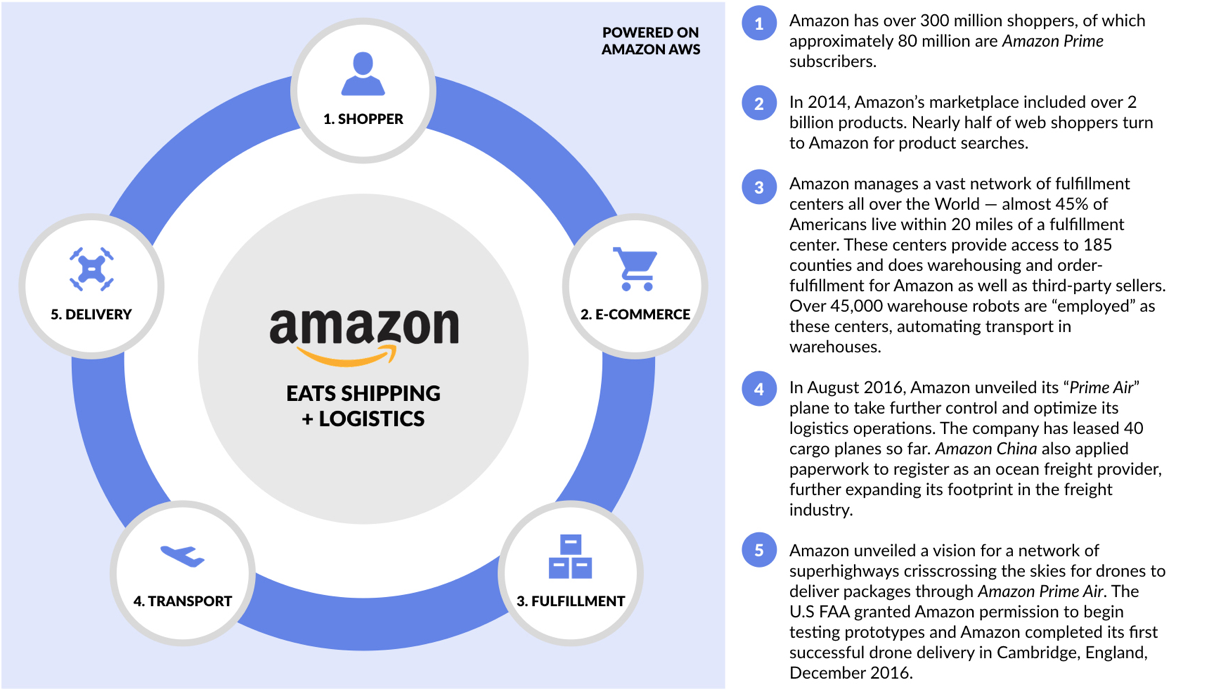

Today, Amazon has over 300 million shoppers, including over 80 million Amazon Prime subscribers. Amazon captures one-third of U.S. e-commerce and is expected to make up over 50% of the market by 2021. The platform has over 2 billion products on its marketplace, fulfilling orders in over 185 countries — basically in every corner of the world.

But what’s core to the success of Amazon’s e-commerce business is its vertical integration. Amazon intends to own every step of the supply chain from the moment the shopper presses “buy” to the moment they receive their package on the doorstep.

Today, approximately 45% of Americans live within 20 miles of an Amazon fulfillment center. Over 45,000 factory robots manage these fulfillment centers, automating the processing and organization of goods to accelerate delivery.

Today, Amazon hands packages off to third-party delivery services such as UPS and FedEx to get the final product to the customer. But that’s changing.

Through an initiative, dubbed “Dragon Boat,” Amazon is seeking to control the flow of goods from factory floor to the front door. It is systematically acquiring space on cargo planes, trucks and ships at reduced rates, to drive down global freight overhead. In support of Dragon Boat, in 2016 Amazon launched a fleet of “Prime Air” planes — 40 rented Boeing cargo jets that it plans to to use for long-haul transport. Additionally, Amazon announced its entry in the freight industry by registering Amazon China as an ocean freight provider.

Eventually, as this process matures, Amazon intends to scale an integrated offering dubbed “Global Supply Chain by Amazon”. Just as Amazon built Amazon Web Services to fulfill its internal computing needs before spinning it out into a $12 billion business, Amazon will do the same for Global Supply Chain, offering the service to merchants of all sizes.

WHAT’S NEXT: SUPPLY CHAIN TO BLOCKCHAIN

At its core, a supply chain is a series of transactions that move products from a point of origin to a point of sale or deployment. While the World’s top manufactures, from Apple to Boeing, have developed competitive advantages through complex, proprietary global supply chains, tracing the origin and movement of products, and paying for them, remains inefficient and error-prone.

Blockchain can optimize supply chains by creating a secure, common record for all key participants to track the origin and movement of goods — from raw materials to components and manufactured end products. Transparency creates efficiencies for all participants, enabling quicker adjustments, more accurate forecasting, and targeted forensics in the case of recalls.

This year, mining giant BHP Billiton began to use blockchain to manage rock and fluid samples from its vendor network — a key input that guides where the company creates mines and oil wells. Instead of continuing to rely on emails and spreadsheets, BHP is partnering with blockchain startups BlockApps and Consensys to create a transparent ledger where technicians taking specimens can attach data (e.g. collection time and conditions) and lab researchers can add detailed reports. All will be immediately visible to anyone with the appropriate access.

IBM handles millions transactions per year, from its own vendor purchases to financing purchases for clients. Disputes, which take 44 days to resolve on average, typically arise over tax rates and missing or incorrect shipments. In September it began using a blockchain ledger that has reduced dispute resolution time to ten days on average. Additionally, Walmart began to work with IBM to follow the movement of pork in China using blockchain, to more easily target and monitor outbreaks.

Startups like Skuchain and Hijro are focusing on supply chain finance — a $2+ trillion market where suppliers borrow against expected receivables from major retailers like Walmart, which often push out their payments by 40 days or more. Financiers have traditionally offered suppliers who are eager to be paid right away the equivalent of payday loans, charging 5-10% for their services. But blockchain can create transparency around the process, providing better visibility into the status of receivables, enabling lenders to offer more competitive rates. This, in turn, enables suppliers to lower prices, as they are no longer burdened by unreasonable borrowing terms.