Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

“October. This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February.”

— Mark Twain

“Some people feel the rain… others just get wet.”

— Bob Dylan

Maybe it’s because the month ends with witches, goblins and ghosts, but October has a reputation as being scary for investors. For those who expected a “Red October,” the tenth month of the year didn’t disappoint, delivering the worst monthly performance since the Financial Crisis.

The S&P 500 was down 6.8% for the month, which was nothing compared to NASDAQ being off 9%. According to Lipper, the average small cap growth manager lost nearly 12%. Ironically, economic data remained robust with 250,000 new jobs created in October, hourly wages rising 3.1% — the best since 2009 — and unemployment reaching at a fifty year low at 3.7%. However, this was bad news for short term investors who feared the Fed’s continued drumbeat of raising rates.

The most spooky to tech investors was the median drop of 21% of FANG AM (Facebook, Apple, Netflix, Google, Amazon and Microsoft) since the beginning of September. These six stocks have contributed 37% of the rise of the S&P 500 since 2013. Alibaba and Tencent (two thirds of the Chinese “BAT”), which accounted for 28% of the rise of the Chinese markets in the past five years, have fallen precipitously from their elevated perches. Add that up and $900 billion of market value has been lost in these eight stocks in the past two months. To put the significance of this carnage in perspective, this is greater than the entire market value of all eight companies a decade ago.

In jittery times, it often seems that companies that open their mouths get punished because it reminds investors they own the stock. Great companies like Apple and Spotify reported impressive results. But that wasn’t enough to prevent the nervous nellies from focusing on the specks of imperfection and send AAPL and SPOT lower. Conversely, fearing the worst for some fallen giants, decent results for Starbucks and Under Armour sent each stock soaring 10% and 28%, respectively.

It’s our strong belief that volatility is the friend of the long term investor. What we like to do is focus on the fundamentals that will drive growth and that over time, earnings and revenue growth drive stock prices. In fact, in the long term, there is essentially an 100% correlation.

One of the strongest predictors of future fundamentals is demographics. For example, as a country’s population gets older, it will spend more on health care. A rising middle class will spend more on branded consumer goods and travel. And as the population becomes more saturated with Digital Natives, it will adopt technology faster and embrace technology solutions.

A study that came out last week said that only 45% Generation Z (people aged 15 to 21) felt like they were in “good” to “excellent” health. This compares to 56% of Millennials who feel healthy, 70% of Baby Boomers and 74% of people over the age of 73. More troubling, 90% of Generation Z says they feel some aspects of depression with the causes being traced to the “Always On” environment of smart phones as appendages and the onslaught of negative news. It’s no wonder that when a 3rd grade class in Boston was asked to design the perfect playground, phones were “banned” unless there was an emergency.

Understanding demographics gives investors a more predictable view to the future. But when it comes to demographics, things aren’t always what they seem. It’s all about thinking outside boundaries and connecting dots.

It is fitting that the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Bob Dylan. Now in the company of T.S. Eliot, Samuel Beckett, and Gabriel García Márquez, Dylan is the first musician to win the award. The Swedish Academy decided to think differently (It’s about time — even the Oxford Book of American Poetry included his song “Desolation Row,” in its 2006 edition, and Cambridge University Press released “The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan” in 2009).

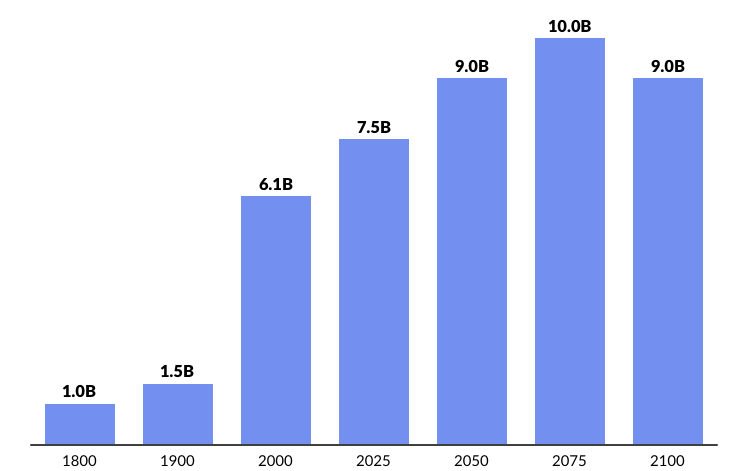

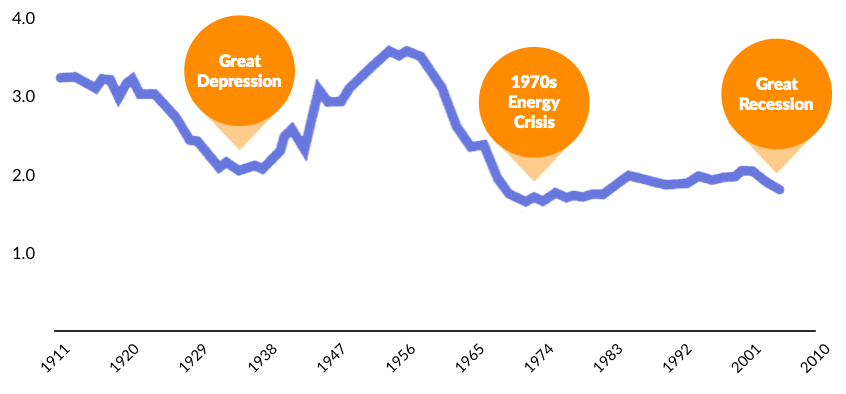

We’ve seen alarming headlines about overpopulation for more than a century and for good reason. If you simply extrapolated the 4x increase from 1900 to 2000, global population would be approximately 25 billion by the end of the century. Obviously, such a boom would likely cause chaos, impacting everything from food to energy, pollution and infrastructure.

But the fact is that the world’s population growth rate is now half of what it was 40 years ago. After peaking at a 2.1% annual population increase in the 1970s, growth hit the brakes.

It took roughly 13 years to welcome the 7 billionth member of the human race in 2012. That’s one year longer than it took to add the 6 billionth member, the first time in human history that this interval has expanded.

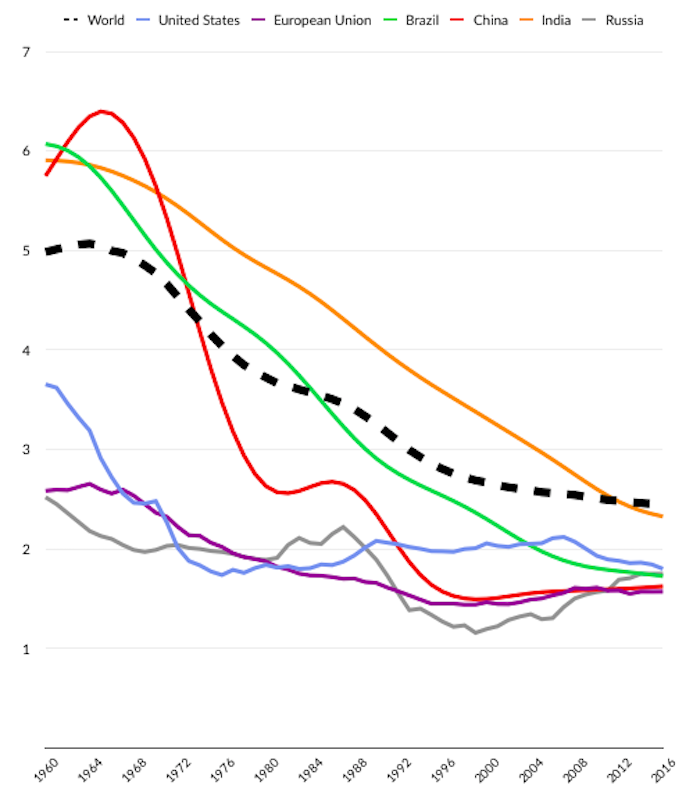

THE GREAT DECLINE: GLOBAL FERTILITY

The force behind the impending population drop is a declining Global Fertility Rate — the number of children an average woman is likely to have during her childbearing years (conventionally defined as 15-49).

Population growth (or loss) is dictated by the interplay of Fertility Rates and Replacement Rates — the average number of children per woman that need to be born to maintain current population levels. In developed countries, the Replacement Rate is essentially 2.0… Two parents are replaced by two children. Since child mortality is higher in developing countries, the replacement rate needs to be higher to maintain population status quo.

In 1950, the global fertility rate averaged about five children per woman. Today, the global average is less than 2.5.

In the 1970s, only 24 countries had fertility rates of 2.1 or less, all of them rich. Today this club has grown to over 95 countries, spanning every continent. Between 1950 and 2000 the average fertility rate in developing countries fell by half, from six to three. Europe went from baby boom to bust over the same period, with fertility rates falling at the same rate to 1.4.

To make an obvious point, carry the math forward and your population is extinguished.

Source: World Bank As fertility falls, countries initially benefit from a saturation of working-aged adults, a phenomenon known as a “Demographic Dividend.” But eventually, this benefit reverses as a top-heavy retired population decreases productive output and imposes disproportionate government service demands on a smaller workforce.

In Japan, for example, there are more adult diapers sold than baby diapers per year. With a fertility rate of 1.44, the country’s population projections are dire.

By 2050, developed countries will have twice as many old people as young ones. And as the demographic tidal waves begin to make landfall, developed countries are no longer turning a blind eye on their population dynamics.

It’s why China quietly reversed the “one-child policy” in late 2015. The draconian measure to promote population stability was initiated in 1979. But China’s fertility rate has dropped to 1.57. By 2050, the result will be a Chinese population of 349 million people over the age 65— larger than the entire United States. The country will scramble to replace desperately needed productivity — the engine of GDP growth — as people cycle out of the workforce.

The number of women giving birth in the United States has been declining for years and in 2017, hit an all-time low. The decline is especially striking because the number of women in their prime childbearing years — 20 to 39 — has been growing steadily since 2007.

The question is, why? There are a few answers. In scary times, parents are reluctant to bring babies into the World. The second is that women are becoming a driving force in all aspects of society and are choosing to have kids later or not at all.

BATTLE OF THE SEXES

On September 20, 1973, more than 50 million people watched Billie Jean King destroy 55-year-old Bobby Riggs in three sets at the Houston Astrodome in what was called the “Battle of the Sexes.” This followed Helen Reddy’s 1972 number-one hit “I am a Woman,” both events inspiring to the women’s movement. Three years later, Margaret Thatcher would ascend to leadership of the UK’s Conservative Party, beginning a 15-year stretch as a geo-political power broker.

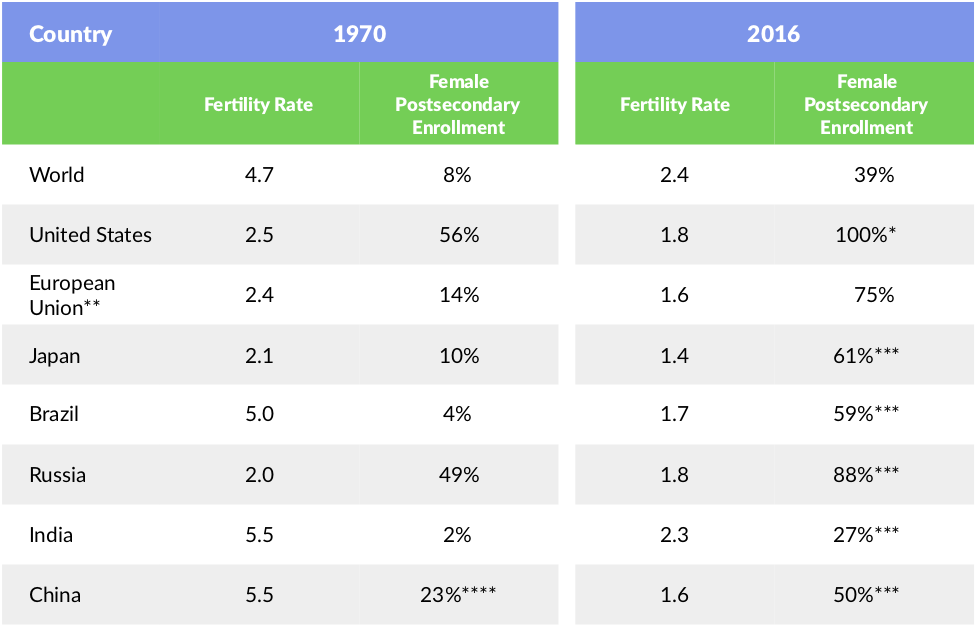

While there are many factors correlated to decreasing fertility rates, with increased opportunity comes the increased opportunity cost of having a child.

In the United States, for example, women with one or more years of college have sharply lower lifetime fertility rates than less educated women. Broader global gains in postsecondary education enrollment by women have also corresponded with declining fertility rates.

Source: OECD, World Economic Forum

*Post-secondary enrollment percentages are calculated by dividing the total number of enrolled female students over the total population of eligible college-ready females. As older populations, that don’t traditionally fall into the college-ready age bracket, enroll in college courses, this skews the percentages such that the percentages could exceed 100%.

**Constituent Countries

***2015

****1976

A related factor in declining fertility rates, particularly in the developed world, is the desire to have children later in life. According to a 2015 study from the Pew Research Center, 41% of women claim that the best strategy to reaching a top job is to have children after achieving career success.

In the United States, for example, child bearing among women aged 30 and over has risen significantly over the last three decades. The number of women giving birth past the age of 45 has been increasingly steadily for decades.

This trend is playing out in the Silicon Valley arms race to lure the top talent. Facebook, Google and Apple offer egg freezing and IVF as a benefit for female employees who choose to delay motherhood. Covering an estimated $20,000 worth of medical services, this is a big ticket benefit. Companies such as Carrot and Progyny provide a suite of fertility benefits for employers, making it seamless for startups to add fertility services as a benefit. The “delayed baby benny” makes perks like massages at your desk seem relatively pedestrian.

Fertility has grown to be a $4 billion industry in the United States, but egg freezing still makes up only a tiny percentage of it. Extend Fertility is working to bring down the price of the procedure to attract a broader segment of the population. Atlanta-based startup Prelude provides couples proactive fertility care to allow women and couples to have more active control over the timing of their pregnancy. The company offers services such as egg and sperm freezing, genetic testing, and embryo control at affordable rates with transparent costs.

CLASS OF 2020

Looking ahead, we’re less focused on how MANY people are walking the earth versus what KIND of people are emerging as the next generation of consumers and entrepreneurs.

Two years ago, the class of 2020 showed up on college campuses across the United States. They don’t know what a Walkman is and would be shocked to learn that people used to smoke in bars. They were three-years-old during 9/11 and have spent more than 80% of their lives in a country at war.

If you go back 18 years, the class of 2020 shares its birthday with Google, which was launched in 1998. Today, there are over four trillion searches per year. This group grew up in a world where information is free and at your fingertips. For me, the is opposite of the world I grew up in when information was expensive and water was free. But this is just the beginning of how different the class of 2020 is than the world I grew up in.

Think how much things have changed.

Just a year before Google’s launch, Steve Jobs returned to Apple for a second tour with the goal of putting a personal computer in every home. The launch of the iPhone in 2007 ultimately put a super computer in every pocket.

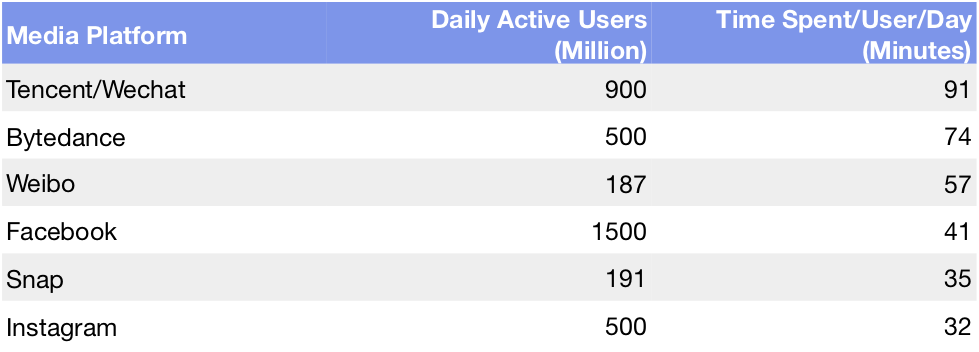

For the class of 2020, the smartphone is just a phone… they expect it to be “smart” as they do with other technology. And that’s just table stakes. They want to access everything on demand — from transportation, to food, retail products, and media.

If you think about entertainment, services like Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube enable you to access anything you want to watch, whenever and however you want to watch it. It’s no wonder that the Class of 2020 thinks that going to a movie theater at a set time to buy overpriced popcorn and soda is ridiculous. Over the last decade, movie admissions per capita the United States and Canada peaked at 4.4 in 2006 and 2007, dropping to 3.8 in 2016.

Not coincidentally, over 50% of the Class of 2020 thinks that online courses are as good or better than the classroom. It’s absurd to have go to a commodity Econ 101 class on Thursday morning at 8:00AM if you can access it on demand.

Interestingly, while the Digital Natives of the Class of 2020 love technology, they have no recollection of the Dotcom Bubble.

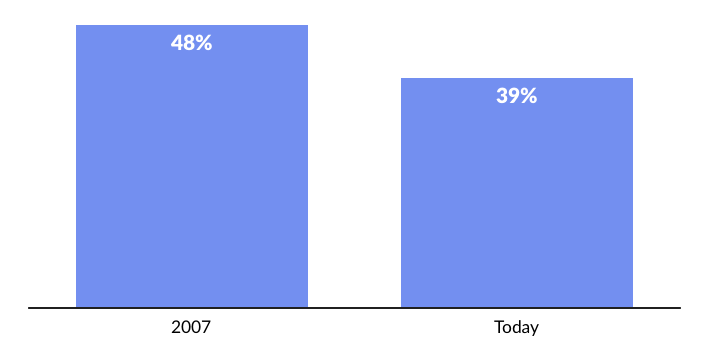

The class of 2020 loves technology but has no recollection of the Dotcom Bubble. They were three-years-old when it burst. But what’s etched in their memory forever is their family, or friends of their family, losing a home to foreclosure during the financial crisis of 2007. Not surprisingly, a decade later, Millennial home ownership is down nearly 20%. They also have no memory of the AOL/Time Warner merger, the “worst merger of the century” and think that the AT&T/Time Warner merger is genius and conceptually gets you the most content for compelling value.

Also etched across the collective memory of the Class of 2020 is parents losing jobs they had for an entire career — and pensions along with it. Not surprisingly, the Department of Labor estimates that the latest crop of graduating Millennials will have over 15 lifetime careers — up from four in 2010. While a number of factors are driving this dynamic, including accelerating digital disruption and globalization, a simple aversion to career commitment has a lot to do with it.

Increasingly, many of these lifetime careers will be a part of the emerging “Gig Economy.” 82% of millennials aspire to be flexible workers. In the United States, 40% of millennials are flexible workers. In China, the percentage is even greater, with 60% of millennials as flexible workers.

Additionally, 82% of high schoolers aspire to be an entrepreneur. Anyone can become an entrepreneur in 60 seconds by monetizing their home, their car, or even their spare cash, by selling services through digital Peer-to-Peer Marketplaces like Uber, Lyft, and Airbnb.

Interestingly, as ride-sharing platforms have surged — Uber raced past two billion rides delivered in 2016 — the demand for car ownership among Millennials has plummeted. According to Bloomberg industry research, last year, more automobiles were sold to people aged 75 and older than 18-24-year-olds.

The precarious new dynamics in the auto industry drive home the disruptive and deeply intertwined elements of the Class of 2020. Powerful, ubiquitous mobile devices enable on-demand services and Peer-to-Peer Marketplaces. Broad demand for these services, in turn, has created widespread part-time work opportunities for a generation that is increasingly unlikely to commit to a single career. And sharing platforms have further reduced the need and desire to purchase physical assets, like houses or cars.