Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

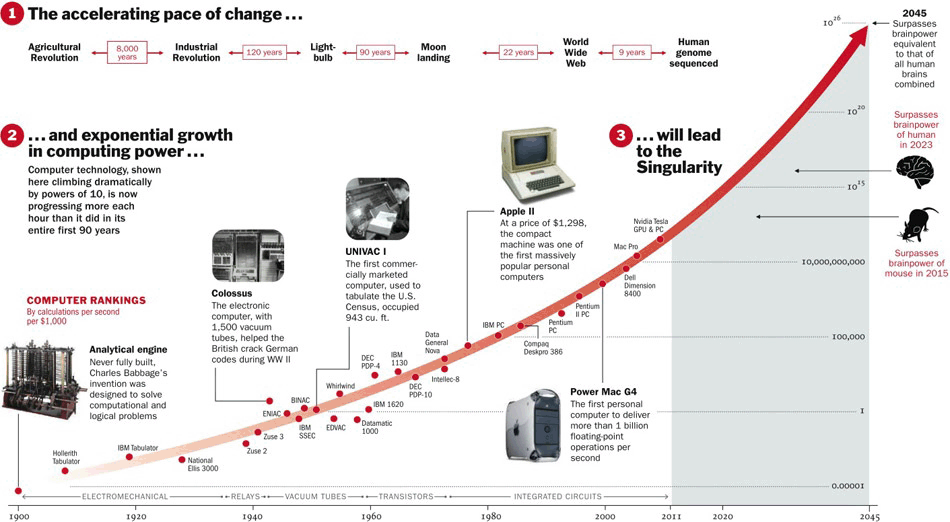

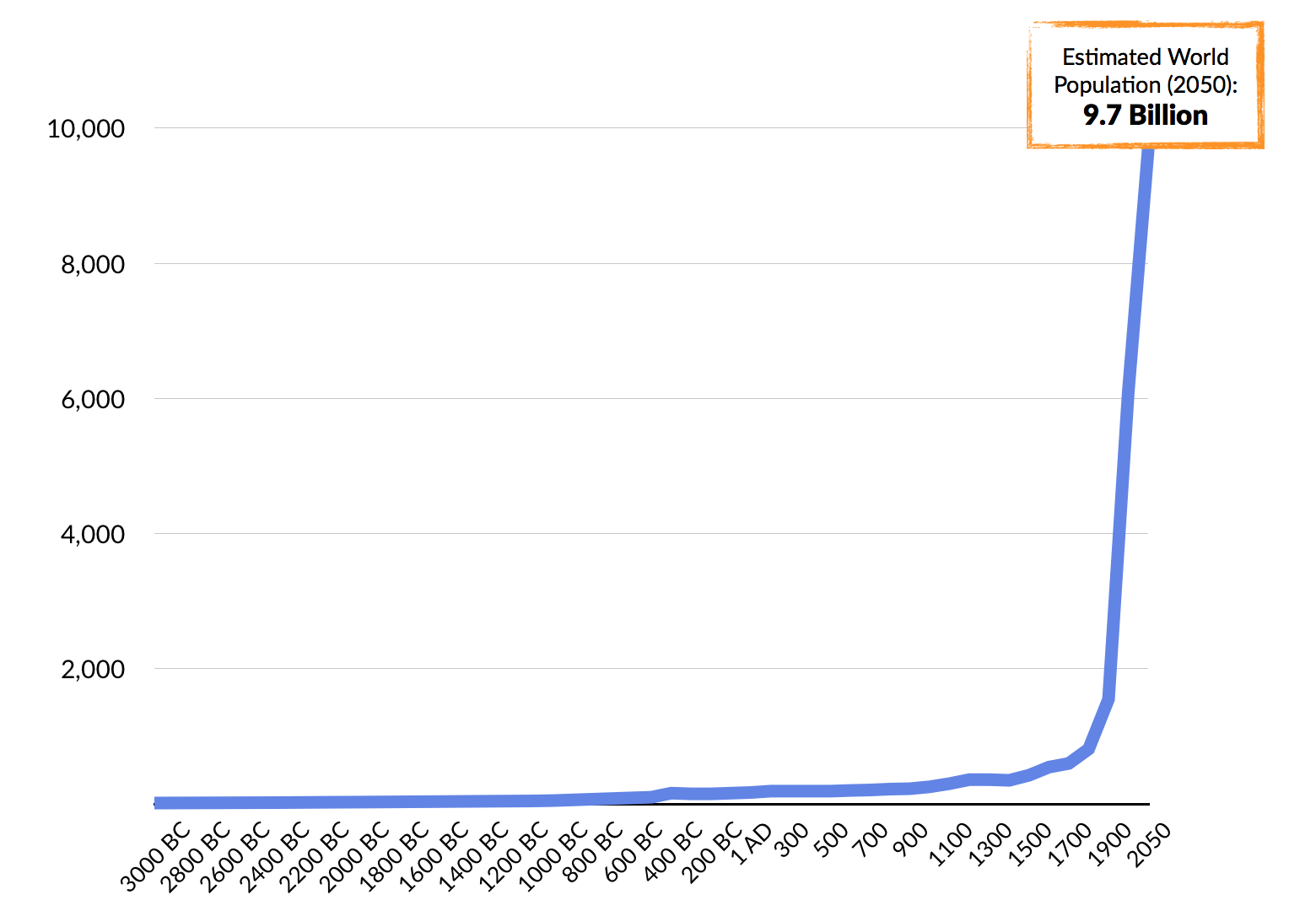

During the time of Christ, the human population on Earth was at a steady 200 million. In the 1800s, at the height of the industrial revolution, the human population passed the 1 billion mark. But today, about 200 years later, the population boomed to be over 7 billion. And by 2050, it’s expected to rise to 9.7 billion.

Movement is in our DNA. Until about 10,000 years ago — or 99% of human history — there were few, if any homes or villages. People were nomadic, chasing food and gentler climates. While we couldn’t change the weather, we learned how to domesticate plants and animals in what is now called the Neolithic Revolution. And when the food stopped moving, so did we.

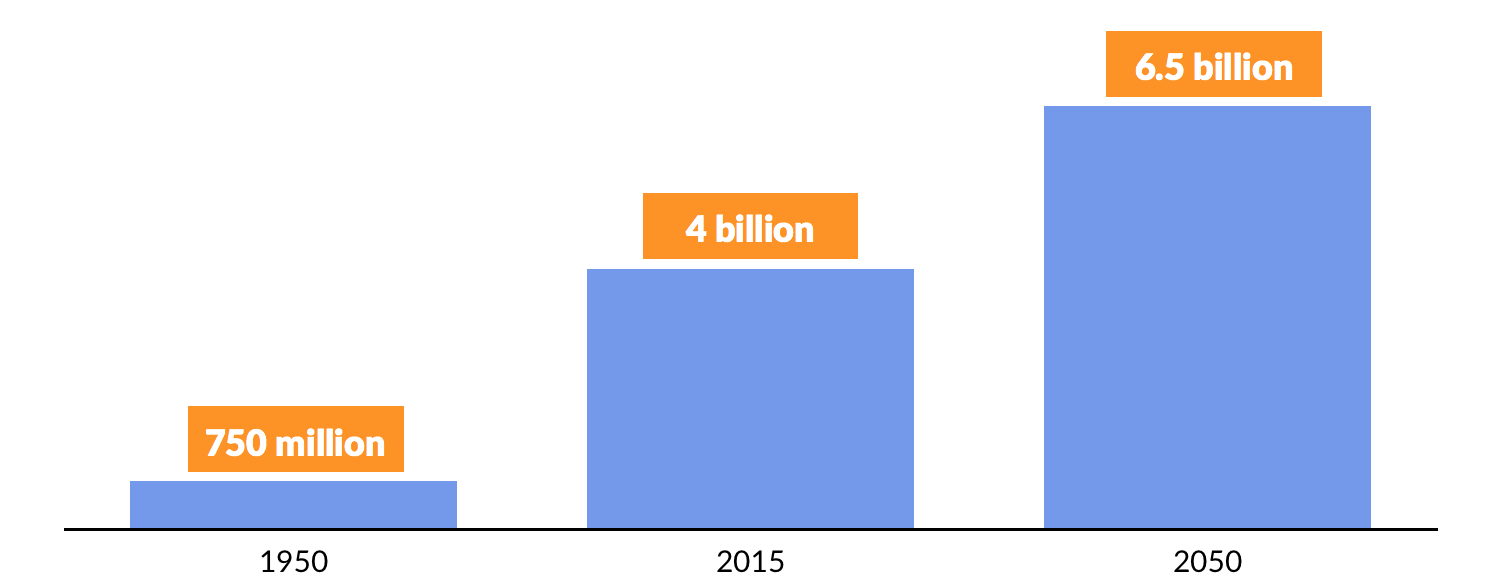

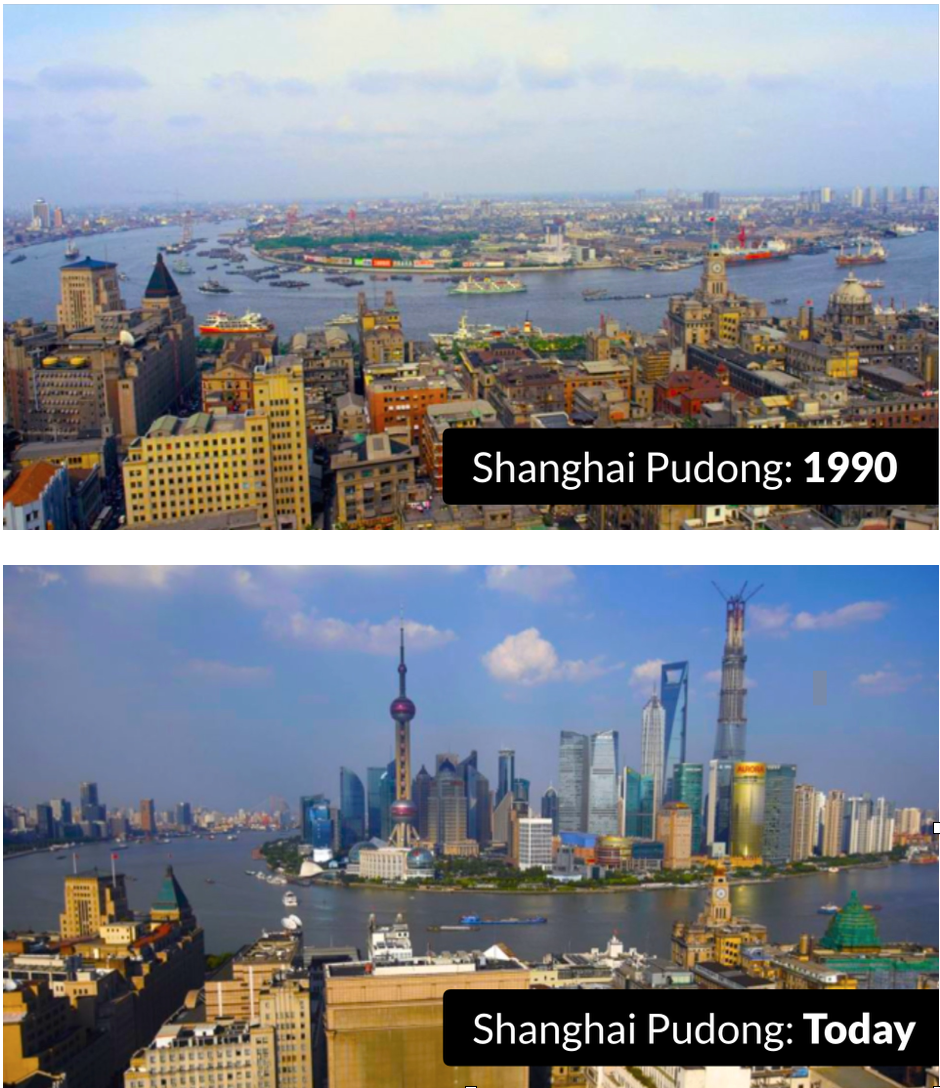

In the next 10,000 years, historians might look back and name our era the “Metropolis Revolution.” Today, the United Nations estimates that four billion people, or 54% of the World’s population, live in cities. In the next 15 years, the Economist projects that urbanization will increase average city density by 30%. By 2050, the ranks of urban dwellers will swell by 2.5 billion to nearly two-thirds of Global population.

Around 80 million people annually move from rural to urban areas, going off the farm and into the harm. As such, the number of megacities — cities with a population 10 million or greater — has doubled in the past two decades, from 14 in 1995 to 31 in 2017. It’s estimated that by 2100, over 80 cities across the World will have a population over 10 million.

The rise of Global urbanization, coupled with a corresponding increase in the number of vehicles on the road, has pushed city traffic to the limit. In Manhattan, during UN Week, driving in traffic from Plaza Hotel to the Midtown Tunnel — roughly a mile — takes longer than flying from New York’s LaGuardia to Boston.

In Mexico City, for example, the city with the most traffic congestion in the World, drivers spend two thirds of their time in the car in gridlock. And with a population of eight million, Mexico City isn’t even considered to be a “megacity” (10+ million population).

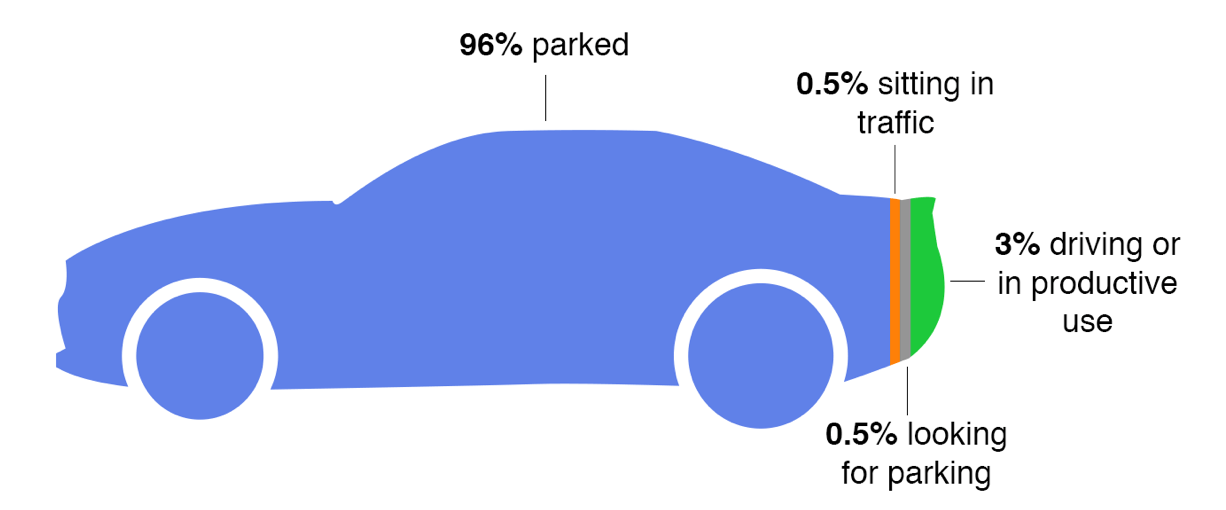

Americans spend over $2 trillion per year on car ownership — more than what we shell out for food. But shockingly, the 250 million cars in the United States spend 96% of the day parked. In other words, there are 240 million cars parked at all times. As Lyft co-founder John Zimmer has observed, BMW doesn’t make the “Ultimate Driving Machine” — it makes the “Ultimate Parking Machine”.

But the millennial generation don’t look to cars as their sustainable source of transportation. Coupled with the rise of ride-sharing platforms, the demand for car ownership among Millennials has plummeted. According to Bloomberg industry research, last year, more automobiles were sold to people aged 75 and older than 18-24-year-olds.

As is often the case, the greatest problems create the greatest opportunities — the bigger the problem, the bigger the opportunity.

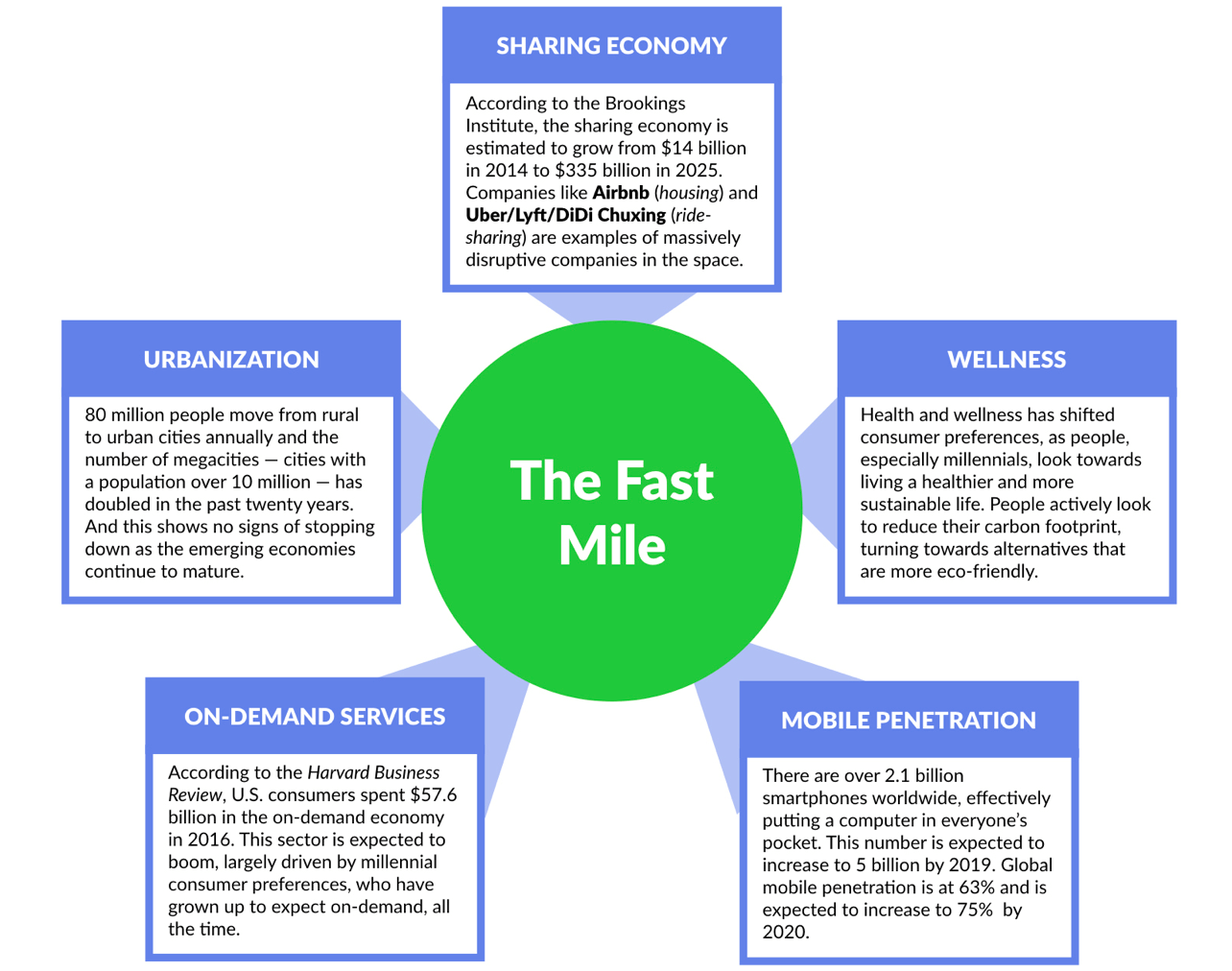

And thats where the “Fast Mile” comes in. Arising at the intersection of several megatrends — the sharing economy, smartphones, urbanization, sustainability, and on-demand services — the Fast Mile encompasses solutions that will add efficiency to the problem of last mile transportation in congested cities.

BIG WHEEL, BIG DEAL

Before the invention of the wheel, 99% of the human population lived, worked and died within a 5 mile radius of where they were born.

But the invention of the wheel around 3500 BC led to a new era of human mobility. Horse drawn carriages were adopted a main source of transportation and bikes — which were first invented in the 1810s — empowered the general population with the option of mobility.

Since then, the core “technology” behind the bicycle has remained largely unchanged. On the flip side, the problem with last mile transportation has only grown exponentially as the population of cities continue to rise. Humanity has and will continue to face the challenge with how to get atoms from Point A to Point B. And while we’re a way off from beaming to places through Star Trek’s Transporter, the rise of fast mile services like shared bikes provide an convenient, affordable and eco-friendly alternative until then.

Bikes were first set free in 1965, when an anarchist group in Amsterdam painted bikes white and left them unlocked for anyone to use. Flyers were posted all over the city stating that “the white bike is never locked.” But eventually they were. The initiative was shut down after most of the bikes were either stolen or badly damaged.

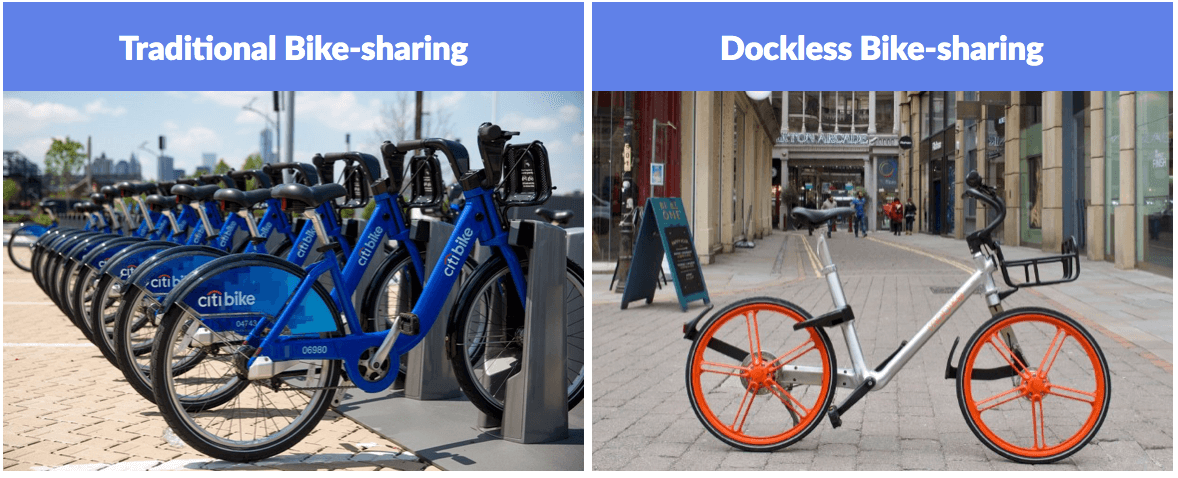

Modern bikeshare systems have been in existence in major metropolitan areas for the past decade. But they never took off, as precursor services lacked convenience, were location specific, and were expensive — usually required a safety deposit of $100 or more. Since 2010, traditional docked bike-sharing services only amassed 88 million trips in the United States.

But suddenly, less than one decade later, bike-sharing has exploded into major markets, with dockless shared bikes seemingly popping up everywhere. What’s changed since then?

Until recently, they haven’t been “smart.” Think about what Uber did to the black car industry. Believe it or not, Carey Limousine was a public company and its claim to fame was providing access to a Global network of high-end taxis. It was a network. Carey didn’t own any cars. Sound familiar?

In a similar way, an emerging group of bike-sharing startups are achieving massive scale — and they’re backed by serious investors. These companies are capitalizing on apps that enable users to easily locate, unlock, use and return bikes through an app.

Traditional bike-sharing services allowed riders to pick up bikes from docks scattered around metropolitan areas. Riders had to ensure that they picked up and returned the bikes to specific locations, otherwise they would be surcharged for their rides. While this service was useful, it didn’t allow riders the full flexibility to use bikes to get from point A to point B.

On the flip side, dockless bike-sharing allows riders to pick up and drop off bikes wherever they want, whenever they want. Riders are able to unlock bikes remotely using a mobile app, ride the bike to their destination, and then leave the bike there for the next rider to use. Unlike traditional bike-sharing services, dockless bike-sharing grants riders the full flexibility to use bikes at their convenience.

THE GLOBAL LAND GRAB

China is home to 10 of the 25 most congested cities in the World. So it’s not a surprise that the two leading bike-sharing companies — Mobike and Ofo — were born in Beijing. They raised over $1.9 billion alone in 2017. Why? In two years alone, these companies have amassed over 100 million users who are completing 25 million rides per day.

What differs between the two services comes down to the experience. Mobikes are considered to be higher-end “vehicles,” costing $440 to build. They have built-in GPS trackers, look like they belong in a SoulCycle class, and cost two yuan an hour to rent.

Ofo’s bikes feel much cheaper, because, well, at $35 to build, they are. With no added bells and whistles, Ofo’s bikes rent for half the price.

While dockless bike-sharing has hit major Asian markets, in Europe and the United States, the movie is just beginning. Global and homegrown players are rushing to secure the prime position in these markets. Mobike (China), Ofo (China), LimeBike (US) and Spin (US) are leading the land grab.

California-based LimeBike’s bright green bikes are now populating the streets of the United States. Founded in 2017, the company officially launched on the University of North Carolina-Greenboro’s campus. The company now operates in 35 markets — ranging from large metropolitan cities like the Bay Area, Los Angeles, Seattle and Washington D.C. to college campuses. Late last year, LimeBike announced it surpassed one million rides, and it is poised to launch in Zurich and Frankfurt.

Interestingly enough, one of the biggest beneficiaries from the bike-sharing boom is the bike manufacturer. Battle FSD, the World’s largest manufacturer of bikes, is partnered with and supplies bikes to many of the new bike-sharing providers, including Ofo and LimeBike. The company currently produces over 26 million bikes annually — a number that is expected to significantly increase as the bike-sharing industry matures.

WHAT’S NEXT

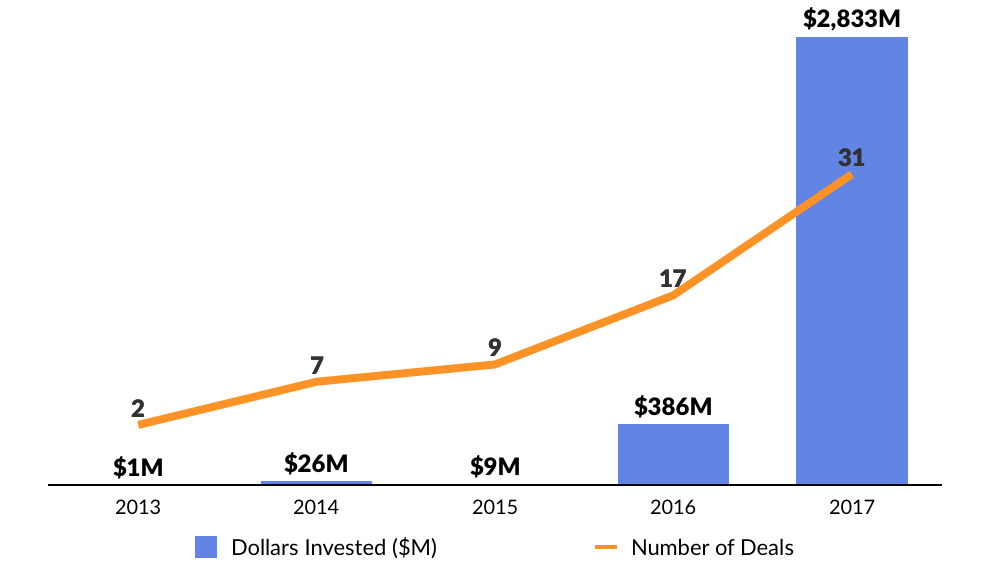

In a few short years, bike-sharing has become the fastest growing sector of the Sharing economy. Venture funding towards bike-sharing startups exploded in 2017, largely driven by the megarounds raised by Ofo and Mobike. According to Pitchbook, $386 million of investment dollars went towards the bike-sharing sector in 2016. In 2017, that number ballooned to $2.8 billion.

Low barriers of entry and quick payback allowed for these bike-sharing companies to scale rapidly. Much like the nascent ridesharing industry, the bike-sharing industry will begin to mature as companies hit market saturation and face competition and heightened regulation from local governments.

Ridesharing Meets Bike-sharing

The Cambrian explosion of bike-sharing has created two Unicorns in three years and the birth of no less than 40 bike-sharing companies. In China, more than 2 million bikes are available from 15 bike-sharing companies. In the US, metropolitans like DC and Seattle are seeing companies like Mobike, LimeBike, Ofo, Spin, and Jump compete for customers. And even Paris, arguably the birthplace of bike-sharing, has been China-fied, with four leading Chinese bike-sharing services taking over the City of Lights.

Much like the early days of the ridesharing industry, the bike-sharing industry will eventually consolidate as major players acquire other services to gain market share in new regions. And it already begun with Chinese firms Youon Bike and Hellobike merging last fall to compete against Ofo and Mobike. Mobike and Ofo themselves have been rumored to begun talks of a merger, though the reports are untrue as both companies are intensely focused on building global market share.

Ridesharing companies are taking on bike-sharing, with almost all of the Global players expanding into the sector. Since inception in 2012, Go-Jek has been the leader in “motorbike sharing” and has grown to be a $3+ billion dollar company from a fleet of only 20 bikes. This January, Go-Jek announced a $1.2 billion investment from Google, Singapore’s Temasek, and China’s Meituan-Dianping.

In the past two months, Dubai’s Careem, India’s Ola, and Southeast Asia’s Grab added bike-sharing services to their platform. In January, on the heels of its acquisition of the struggling Bluegogo, China’s DiDi Chuxing revealed that they too will launch their own bike-sharing platform.

And this week, Uber announced Uber Bike, a pilot which will launch in San Francisco next week in partnership with JUMP. Uber customers will be able to book JUMP bikes through the Uber app.

E-bikes + E-scooters

Down the line, keep an eye out for the proliferation of other fast mile services, such as dockless electric bikes and scooters. In San Francisco, Jump Bikes is launching their fleet of electronic dockless bikes under an exclusive 18-month permit.

Motivate and LimeBike both announced the launch of their e-bikes earlier this year. Motivate will make their electric fleet available through the Ford GoBikes system starting in April. LimeBike will start rolling out their Lime-E fleet this month starting in Seattle and Miami.

And companies are going beyond electric bikes to provide other shared electric transportation services. Scoot is currently operating a fleet of shared scooters in San Francisco, allowing commuters to easily travel through the city in Cherry red Vespa-type scooters. Down the coast, Santa Monica-based Bird currently provides electric scooters in the Los Angeles region.

Regulation

Earlier this month, San Francisco signed an agreement to allow JUMP Bikes have exclusive rights to operate in the city, shutting out competitors LimeBike, Ford GoBike , Spin, Ofo and Mobike completely for 18 months. But that may be too little, too late, as San Franciscans have already taken notice — and reacted — to the influx of colorful bikes on their streets.

Before dockless bike-sharing services have gotten away with negotiating with and getting operating permits from local governments. Companies now are under heightened scrutiny as cities take notice. For example, Santa Monica’s Bird recently got hit with a lawsuit by the city of Santa Monica for their dockless scooters.

And in China — the “Kingdom of Bicycles” with over 20 million shared bikes — the problem is exponentially worse. Shares are often discarded, stolen or heavily vandalized on the streets. One bike-sharing startup Wukong reportedly lost 90% of its bikes in the first six months. Already, cities are beginning to crackdown on issue. In Shanghai, the city hauls away thousands of bikes at a time that clog the streets and sidewalks. And in Xiamen, a bike graveyard exists that is filled with yellow, orange and blue bikes.

And to make things worse, Chinese bike-sharing companies wage wars against each other, purposely sabotaging each other by displacing one another’s bikes. As written in the New York Times:

One morning recently in Shanghai, I caught a glimpse of some suspicious behavior. I was walking down a tranquil, tree-lined street when a muscular man lumbered past carrying two orange-and-silver Mobikes. As he swept by, a wheel touched the ground and set off an alarm, causing him to heave the bikes even higher in the air. The man was not a bike enthusiast, but he wasn’t a thief, either. As I watched him slip down a side alley and emerge moments later empty-handed, I realized that he was a foot soldier in the bike-sharing wars, dumping competitors’ bikes in hard-to-find places. Rounding the corner, I saw the result of his handiwork: a sea of bikes in almost every hue. Yet not a single orange-and-silver Mobike was in sight.

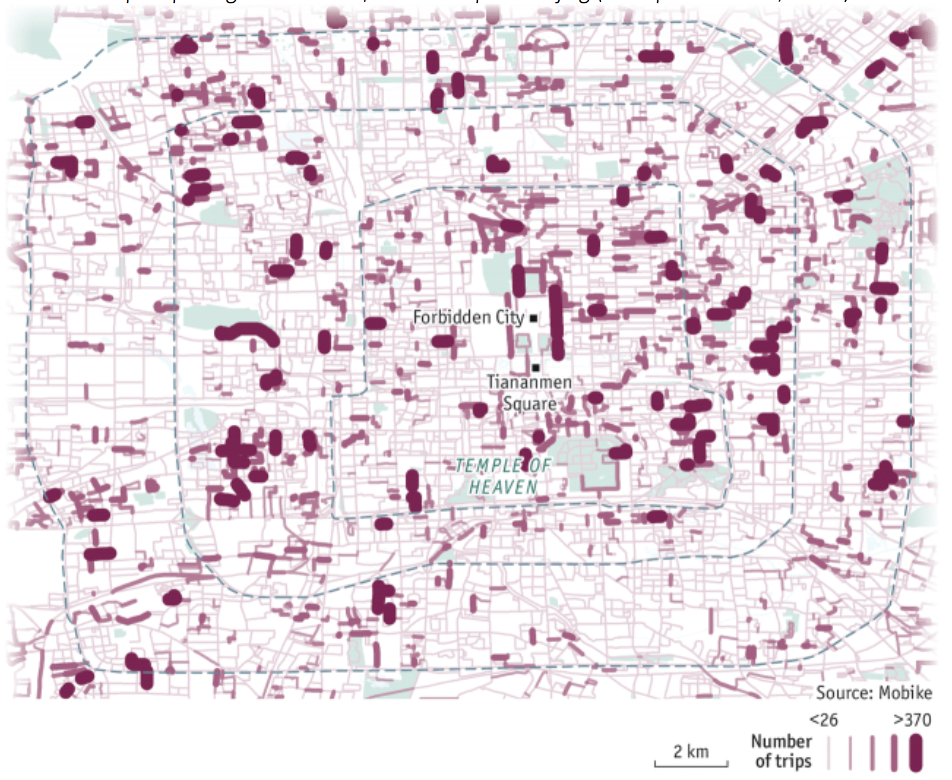

But what’s most interesting here — and arguably how bike-sharing companies attract so much venture funding — is the Big Data play. Cities and businesses are enticed to work with bike-sharing companies to unlock the valuable data that these companies glean from their customers.

Already, Mobike shares its data with think-tanks, universities, research institutes, and the World Bank to support city-planning development efforts. Ultimately, daily transit data on the movement patterns of millions of citizens could result in the creation of powerful initiatives that cut emissions, reduce congestion, and increase quality of life.