Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

On April 3, 2012, the Seattle Times ran a story titled, тАЬAmazon Warehouse Jobs Push Workers to Physical Limit.тАЭ The central character was 51-year-old Connie Milby, who covered more than 10 miles per day in her tennis shoes moving packages from shelf to shelf at an Amazon warehouse in Kentucky.

тАЬAs long as my body holds up, I will keep working,тАЭ Milby reflected on her $12.50-per-hour job. тАЬBut the way it feels, I donтАЩt know how long that will be.тАЭ Not exactly the stuff of FortuneтАЩs Best Companies to Work For list.

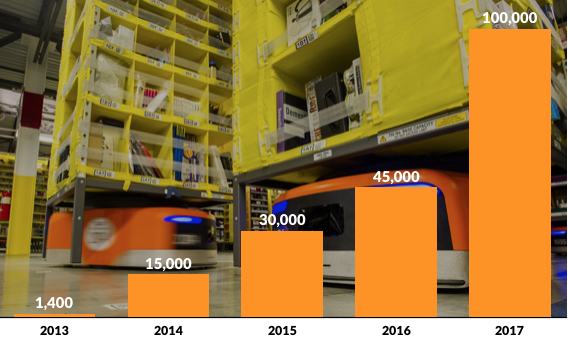

Today, Amazon тАЬemploysтАЭ over 100,000 Kiva robots, which now account for nearly 20% of the companyтАЩs total workforce. You wonтАЩt be reading interviews with them any time soon, but rest assured these sturdy warehouse workers can move 10 miles without breaking a sweat.

What happened? It all started a month before MilbyтАЩs interview.

In March of 2012, Amazon announced the acquisition of тАЬmaterial handlingтАЭ robotics maker Kiva Systems for $775 million. The second largest M&A deal in AmazonтАЩs history, it seemed like a classic Jeff Bezos moonshot.

Kiva made clunky warehouse robots that looked like oversized orange hockey pucks. Wall Street analysts noted that the price tag was a 300% premium to the companyтАЩs last private valuation. It was led by a former employee of Webvan, the high-flying delivery service that went belly up in the dot-com bust.

It turns out the Bezos was on to something. Amazon knew what KivaтАЩs robots were capable of when it acquired the company based on pilots with Zappos.com and Diapers.com. By the time Amazon fully implemented the new technology in 2014, the company demonstrated that it could cut the тАЬclick to shipтАЭ cycle down from the approximately 75 minutes humans required to just 15 minutes. Kiva-enabled warehouses operated with 20% reduced operating costs.

Is the robot revolution upon us? YouтАЩll have to ask Alexa. We believe that rapidly changing technology fundamentals, coupled with broader robotics applications across a variety of industries, signal an inflection point for an industry that has not yet seen the MooreтАЩs Law-type scaling that the world has come to expect from other innovation areas.

STATE OF PLAY

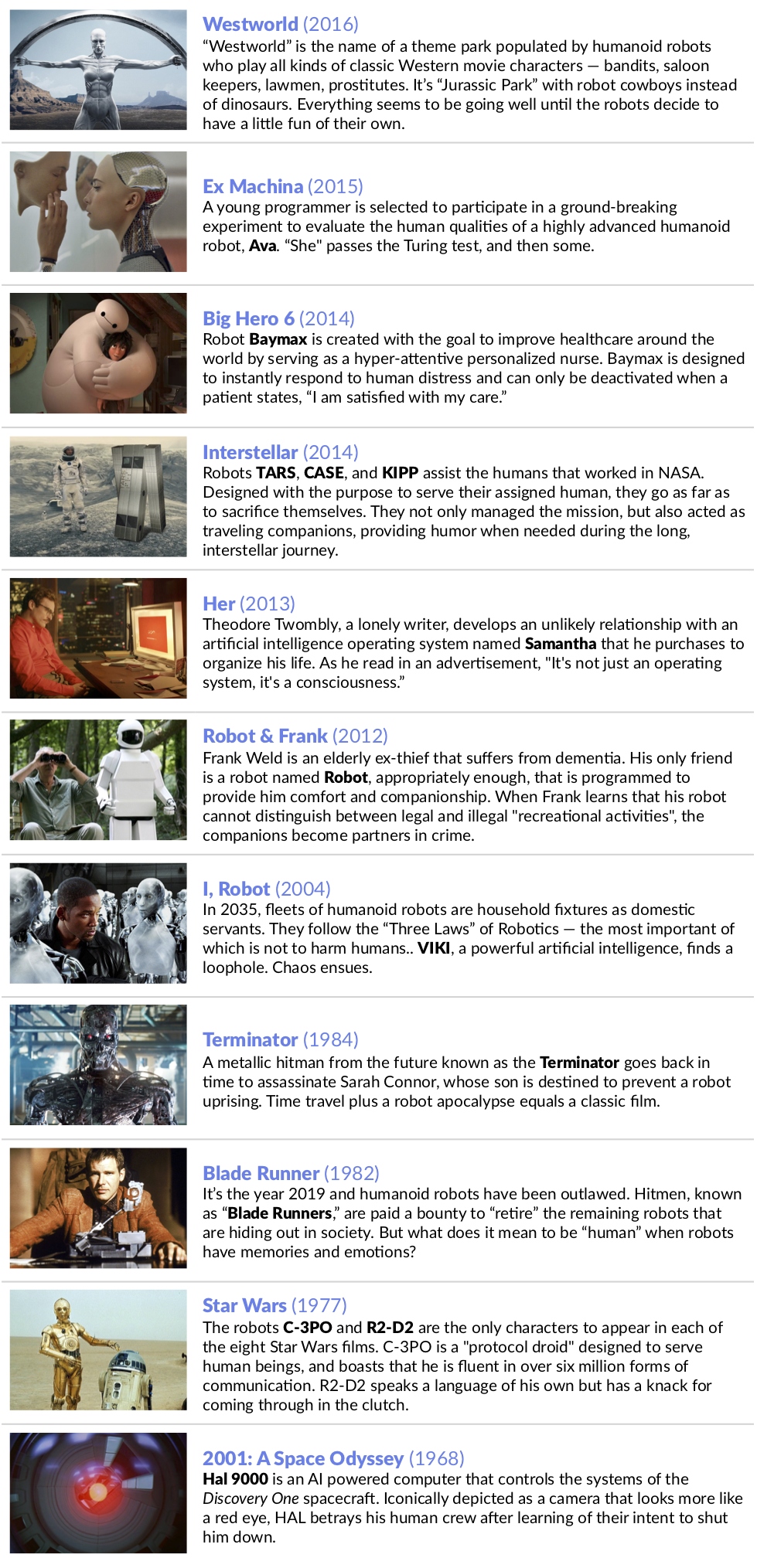

Science Fiction allows you to picture a future that might otherwise be unimaginable. Not coincidently, many of the great innovators and inventors were science fiction devotees, and you can see in modern devices. ┬а┬а

The iPad and iPhone? Go back to the Starship Enterprise and check out the devices Scotty and Spock were using. The Apple Watch? Dick Tracy had one in 1946.

WeтАЩve seen robots on the silver screen for nearly a century, often in galaxies far, far away. Most have human-like intelligence тАФ just a lot more of it. Some are friendly. OthersтАж wellтАж watch Terminator or the Matrix.

Are these visions crazy? Maybe. But weтАЩre closer to the robots of our imagination than you think. Rapidly improving technology fundamentals, transformational developments in Artificial Intelligence, and accelerating investment activity means that science fiction is quickly becoming science reality.

1. New Technology Fundamentals

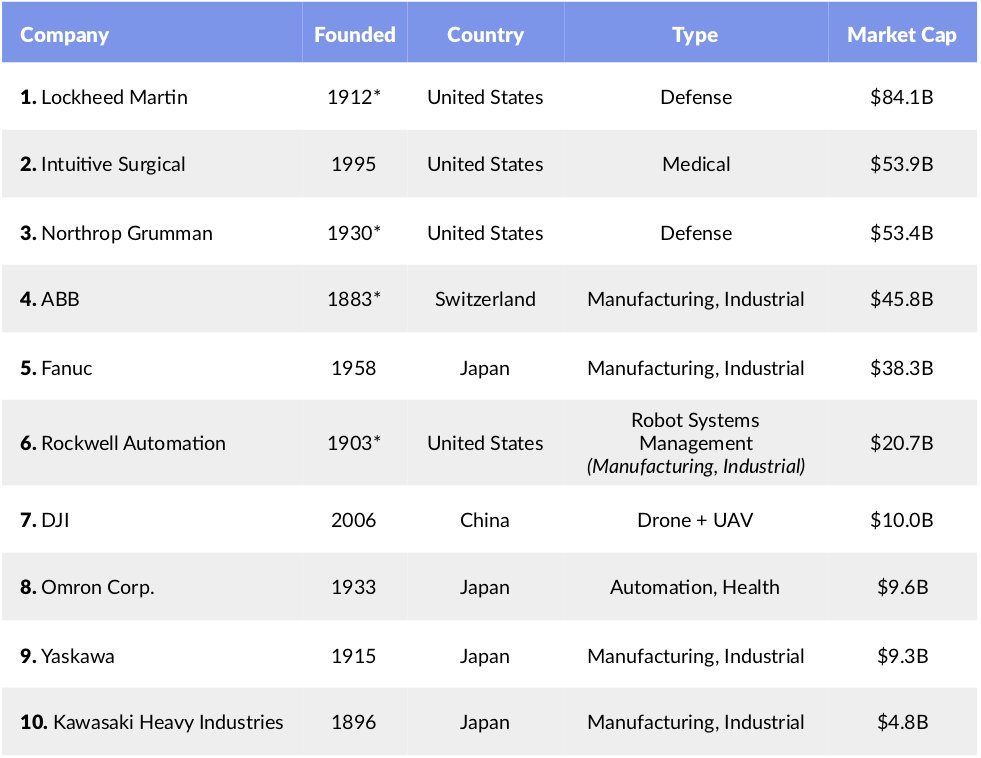

Until recently, robotics innovation and production of any significance has been largely limited to a small group of industrial conglomerates in the United States, Japan, and Germany. Six of the ten largest robotics manufacturers are over 100-years old.

*Lockheed Aircraft Co, and Glen L. Martin Co. each founded in 1912, merged in 1995; ASEA (est.1883) and Brown, Boveri & Ice (est. 1891) merged in 1988 to form ABB; Northrop Corp. (est. 1939) purchased Grumman Corp. (est. 1930) in 1994; Rockwell International acquired Allen Bradley Co. (est. 1903) in 1985 to form the predecessor to Rockwell Automation

*Market Cap as of August 1, 2018

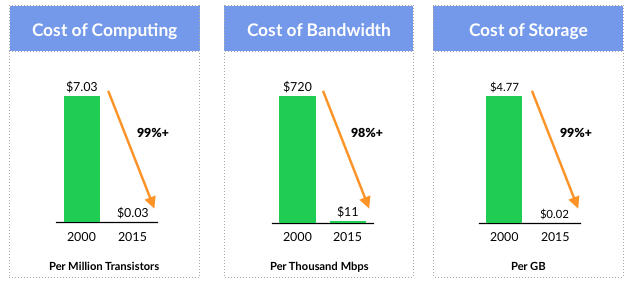

A key megatrend that is opening the door for new market entrants is the rapid decline of technology costs, from hardware components to computing horsepower.

From 2000 to 2015, computing power increased over 100x, while the cost of computing and storage fell more than 99%. During the same period, the price of bandwidth decreased over 98%. Welcome to a world ruled by MooreтАЩs Law.

Smartphones тАФ which didnтАЩt exist until 2006 тАФ are the manifestation of these new technology fundamentals. Today there are nearly three billion smartphone users with computers in their pockets more powerful than the 1969 NASA command center machines that landed men on the moon.

MooreтАЩs Law has driven down the cost of robotic components and enabled entrepreneurs to create machines that are faster, smaller, cheaper, and more powerful. Anki, for example, is a company founded by Carnegie Mellon engineers that is developing toy robots using the same components that power autonomous vehicles. Their flagship product Cozmo тАФ a friendly looking bulldozer that is for all intents and purposes self-aware тАФ would have been unimaginable a decade ago. Anki has raised over $157 million from a syndicate of leading venture capital firms, including Andreessen Horowitz.

Despite the transformative impact of MooreтАЩs Law, technology challenges to scale still remain for entrepreneurial robotics companies.

For large-scale industrial robots, installation can be as expensive as the robots themselves. Autonomous robots remain capacity strained by battery technology that has only improved incrementally since the 1970s. And we havenтАЩt even considered the social stigma associated with machines that are presumed to eliminate human jobs.

Add it all up and the robotics industry appears to be in the age of the Blackberry before Steve Jobs unveiled the iPhone in 2007. Most of the technology components are in place. Robots are heavily used in narrow segments, primarily in the manufacturing sector. With the right design and positioning, the iPhone scale could be around the corner.

2. The Age of тАЬSmart RoboticsтАЭ

In the old world, robots were deployed to complete precise, repetitive work, in carefully designed settings like an assembly line. Adaptability was neither a capability nor a priority. ThatтАЩs all about to change.

Deep Learning is a field of Artificial Intelligence where computers тАЬteachтАЭ themselves concepts and tasks by crunching large sets of data. ItтАЩs a way of getting computers to know things when they see them by producing rules that programmers cannot specify. In other words, itтАЩs a way to develop smart machines at scale much faster than previously imagined.

For example, FacebookтАЩs facial recognition algorithm, Deep Face тАФ which can recognize human faces with 97% accuracy тАФ was created by feeding computers with millions of images of faces. The same principle can be applied to teach a car what a тАЬStopтАЭ sign is, or how to merge onto a highway.

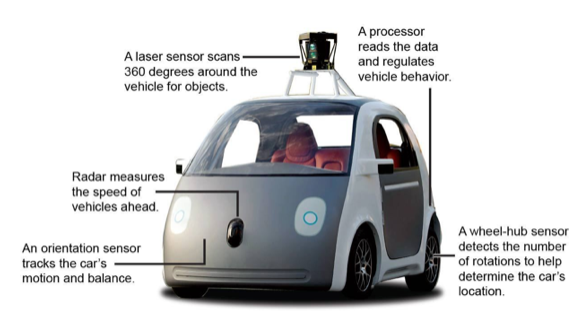

The self-driving car is a prime example of тАЬsmart robotics.тАЭ Autonomous vehicles couple location information from fixed sensors with maps of the world to navigate. Programs processing optical data then generate instructions for the carтАЩs motor and steering systems. Most importantly, applying advanced Artificial Intelligence approaches like Deep Learning enables self-driving cars to тАЬlearnтАЭ from their surroundings.

тАЬCloud RoboticsтАЭ is another trend accelerating innovation in the robotics sector. As Keith Nosbusch, the former CEO of Milwaukee-based Rockwell Automation observed in a 2014 interview with the Financial Times, тАЬManufacturing has always been producing a lot of data тАФ but generally it hasnтАЩt been used. But the data can be incredibly useful. When something goes wrong тАФ a pump fails or a valve breaks down тАФ it can be turned into something that tells you why.тАЭ

Cloud-based data networks enable engineers to more efficiently design and optimize robotic performance (or, in the case of Deep Learning, robots optimize their own performance). Open source platforms like ROS тАФ Robotic Operating System тАФ have been a boon to researchers and entrepreneurs alike. ROS provides a standard platform for programming robotic components. It also provides libraries and algorithms for vision, navigation, manipulation, and other capabilities.

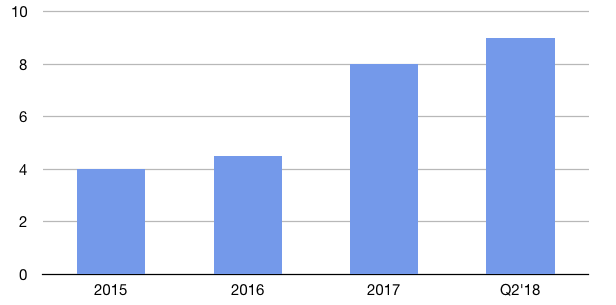

3. VC Investment Activity

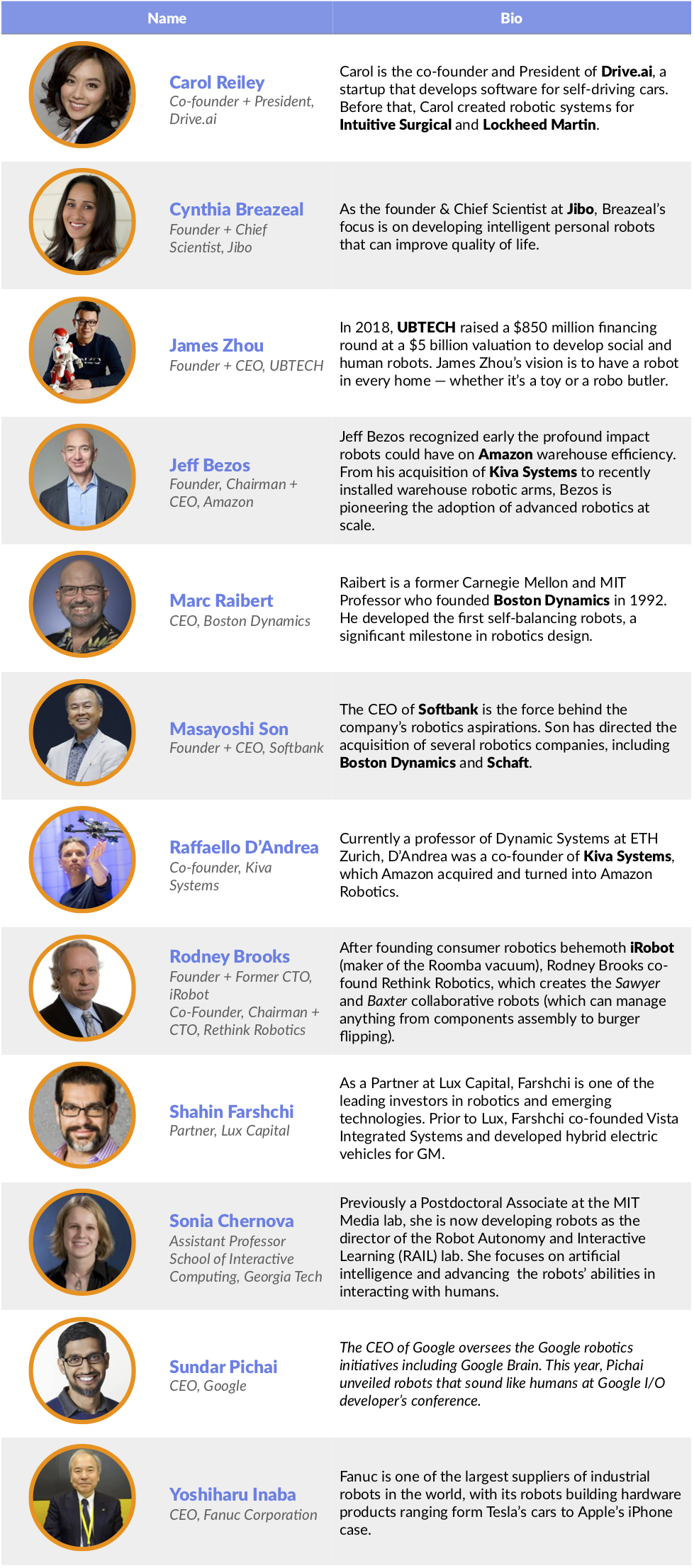

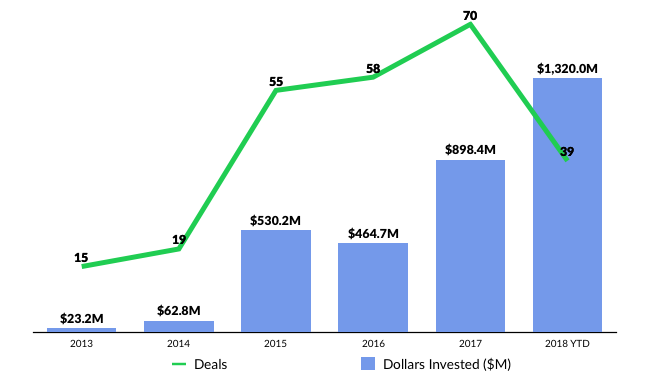

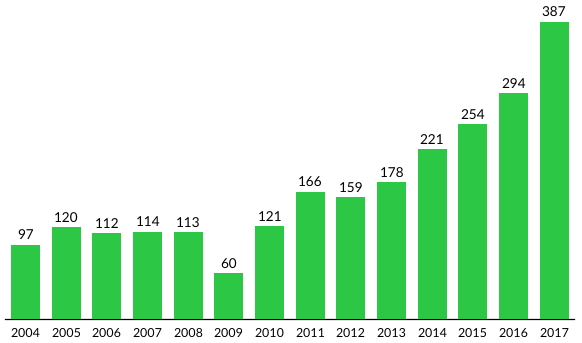

A key indicator of accelerating innovation in the robotics sector is growing interest from venture capital firms. According to CB Insights, since 2010, VCs have deployed approximately $7.8 billion into robotics startups across nearly 1,200 deals. Over $6 billion of these investments have occurred over the last five years.

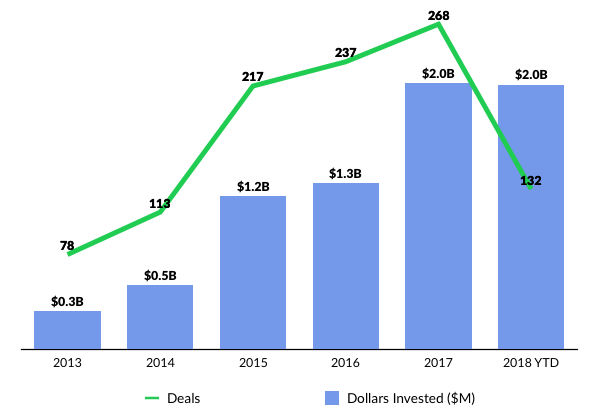

In the first half of 2018 alone, over $2 billion of funding has been deployed across 132 robotics deals тАФ equal to all investment activity in 2017. Notably, UBTECH, an Artificial Intelligence-powered humanoid robot company producing everything from toys to robo butlers, raised $820 million in a May Series C financing. The round was led by Chinese social media behemoth Tencent. After the investment was announced, UBTECH CEO James Zhou indicated the company would use its war chest to accelerate its vision of bringing robots into the home.

CORPORATIONS DO THE ROBOT

Corporate investment in robotics startups has accelerated alongside venture capital activity, surpassing $2 billion across more than 100 deals since 2017.

Over the past few years, leading technology companies, including Amazon, Alphabet (Google), Softbank, Foxconn, Qualcomm and GE, have aggressively moved into the field of robotics.

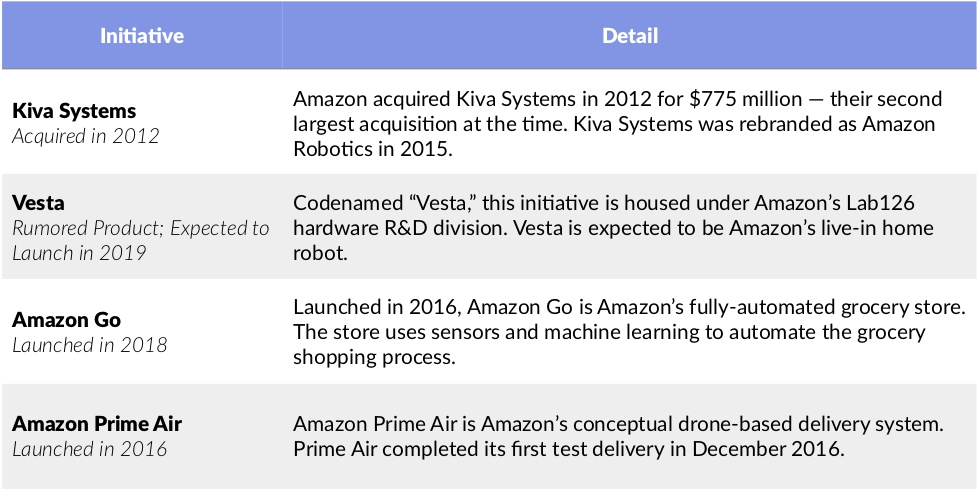

Amazon

Beyond AmazonтАЩs aggressive integration of Kiva robots and mechanical arms into its warehouses, the company is incubating a variety of robotics initiatives. It is reportedly working on a home robot dubbed тАЬVestaтАЭ, the Roman goddess of home and family. This initiative is housed under AmazonтАЩs Lab126 hardware R&D division тАФ the same group that developed AmazonтАЩs Echo and Kindle devices.

ItтАЩs unclear what tasks an Amazon robot might perform. According to Bloomberg, тАЬpeople familiar with the project speculate that the Vesta robot could be a mobile Alexa, accompanying customers into parts of their home where they donтАЩt have Echo devices. Prototypes of the robots have advanced cameras and computer vision software and can navigate through homes like a self-driving car.тАЭ

Alphabet (Google)

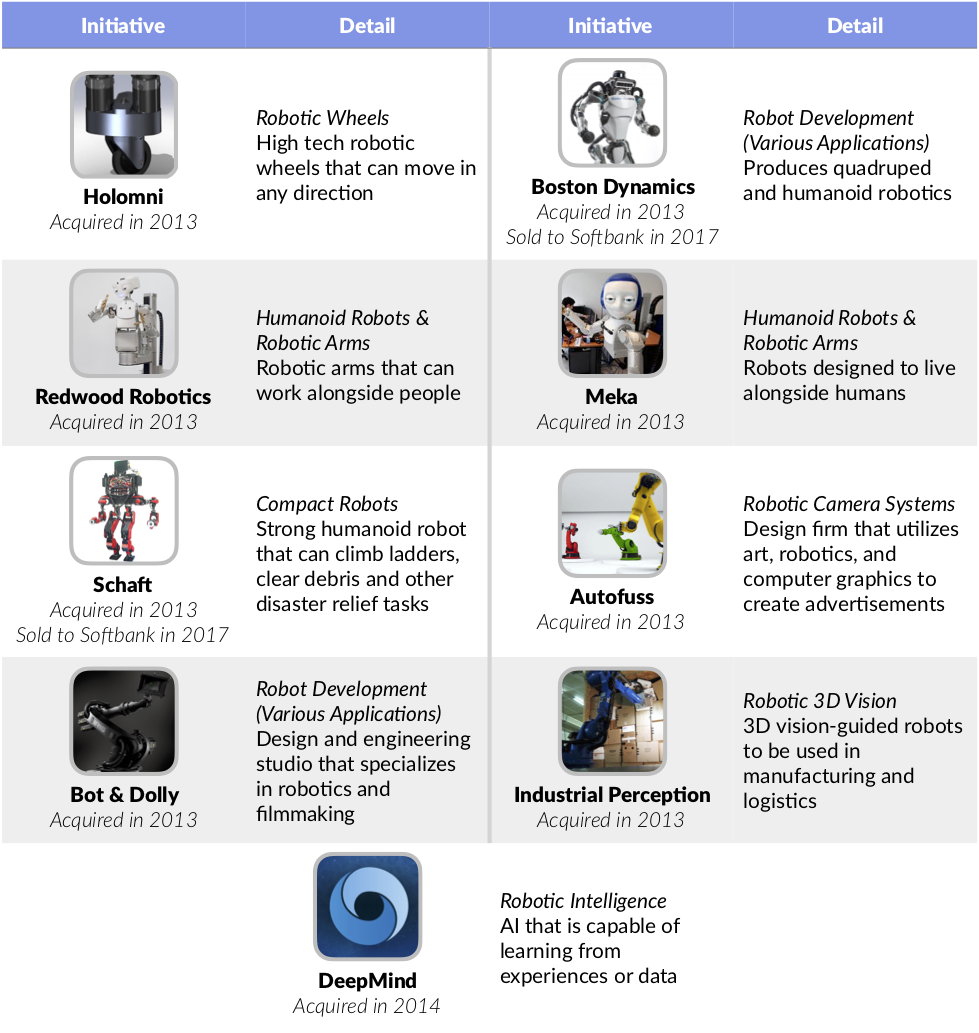

In just over a year, Alphabet kickstarted the creation of a robotics innovation arm, acquiring eight promising robotics startups beginning in 2013.

The company kept its plans close to the vest, but it appeared intent on applying the technology a broad array of autonomous systems тАФ from self-driving cars to warehouse work, package delivery, and even elderly care.

But in 2014, Andy Rubin, the founder of GoogleтАЩs robotics division and the brainchild behind the acquisition spree, left the company to start his own incubator for hardware startups.

In retrospect, it signaled a shift in AlphabetтАЩs strategic priorities.

In 2017, Alphabet sold off two of its robotics acquisitions тАФ Boston Dynamics and Shaft тАФ to SoftBank. The remaining acquisitions have seemingly been left on the back burner, with no commercial application beyond AlphabetтАЩs walls.

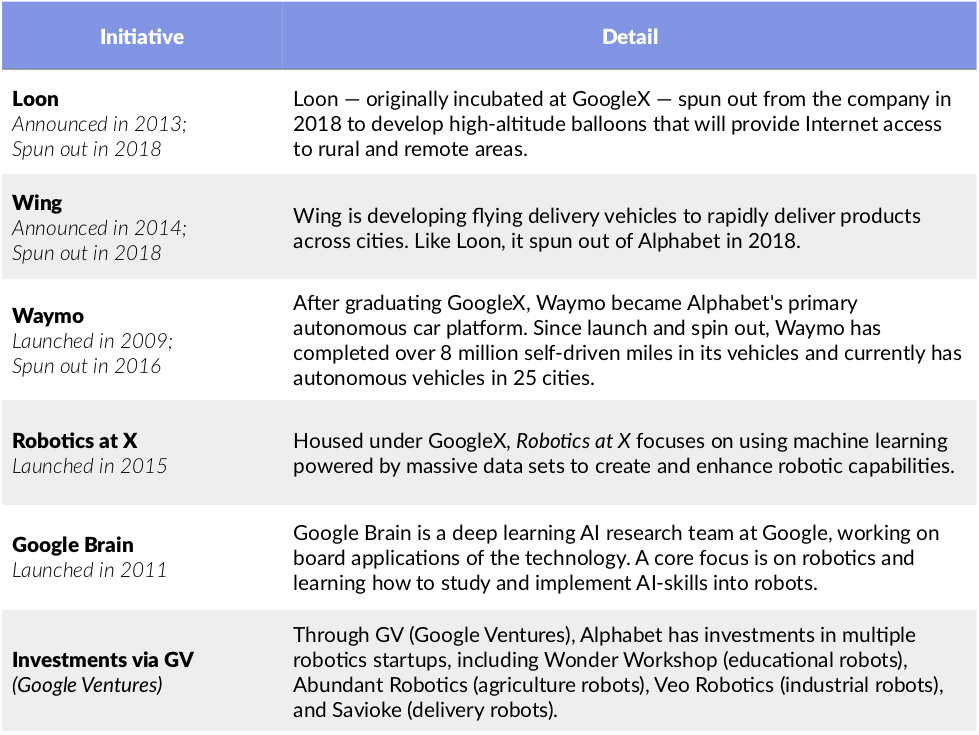

Instead, Alphabet appears to be focusing its attention on creating a software layer for robotics, much as Google maps is an enabling layer for autonomous vehicles. The companyтАЩs тАЬRobotics at XтАЭ initiative, for example, is investigating how machine learning powered by massive data sets can be used to teach robots new skills that will enable them to reliably perform useful tasks in unstructured environments.

On the venture side, Alphabet continues to be active in investing in robotics startups through its venture arm, Google Ventures. To date, it has backed companies including Wonder Workshop (educational robots), Abundant Robotics (agriculture robots), Veo Robotics (industrial robots), and Savioke (delivery robots).┬а

ROBOTICS: KEY INDUSTRIES & APPLICATIONS

Industrial & Manufacturing

Manufacturers like GM have integrated robots into assembly lines since the 1960s when the automaker installed a hulking 4,000-pound arm called the тАЬUnimateтАЭ to attach die castings to car doors.

Today, a new generation of startups is applying advanced robotics to automate a broad range of nuanced physical processes. The most integrated use of robotics can be found in the industrial and manufacturing sectors due to the sheer number of repetitive tasks that can be made more efficient through automation. Bots are increasingly popping up in warehouses and retail settings as well.

While AmazonтАЩs Kiva robots buzz around busy warehouses, LoweтАЩs and Walmart are bringing inventory management robots developed by Bossa Nova Robotics to their store aisles. Bossa bots roam the aisles to scan the shelves and catalog products, enabling Walmart employees to focus on providing better service to customers. Once a bot notices that a shelf is low on a product, the machine pings an alert to an employee to restock, optimizing everyoneтАЩs time.

In four years, Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Foxconn has eliminated over 400,000 jobs in favor for manufacturing and warehouse robots. The company already produces 10,000 тАЬFoxbotsтАЭ annually and intends to aggressively automate its sprawling workforce moving forward. It is estimated that Foxconn employs over one million workers in China alone. The company plans to reach a 30% level of automation by 2020.

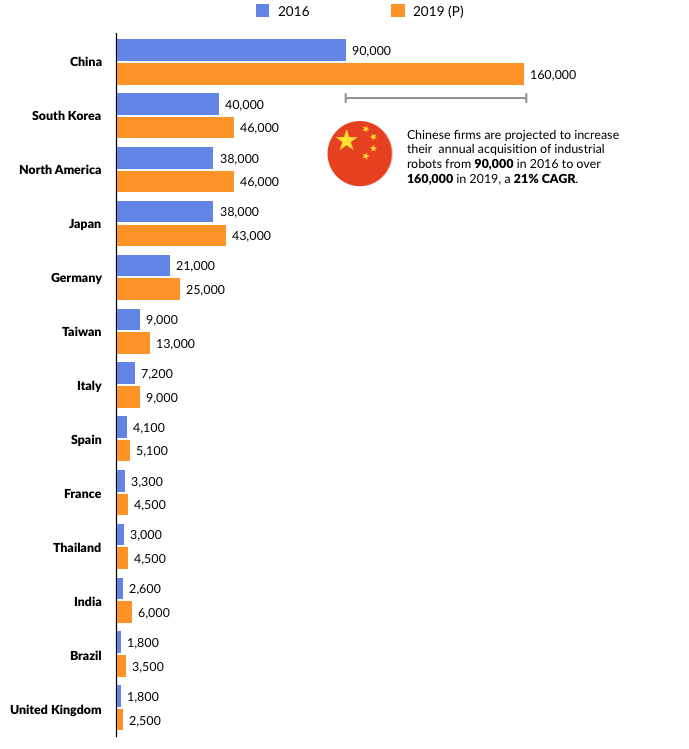

In this context, тАЬChinaтАЭ itself might be the key megatrends in industrial and manufacturing robotics. To date, the worldтАЩs largest producer of everything from clothes to electronics, has depended on low-cost, low-skill labor. But as economic growth slows and wages continue to rise, manufacturers are aggressively adopting robotic solutions.

In 2015, China announced their government-backed тАЬMade in China 2025тАЭ plan, which emphasized the nationтАЩs focus on innovating in cutting edge technology industries, including robotics. As a part of this plan, China declared they want to build at least 100,000 industrial robots per year by 2020. The country looks to be on track, deploying over 138,000 robots in 2017 тАФ a more than 50% increase from 2016. Compare that to the United States, whose robot workforce only grew by 5% in the same period.

Transportation + Delivery

A key industry that will be transformed by driving and flying robots is delivery and logistics.

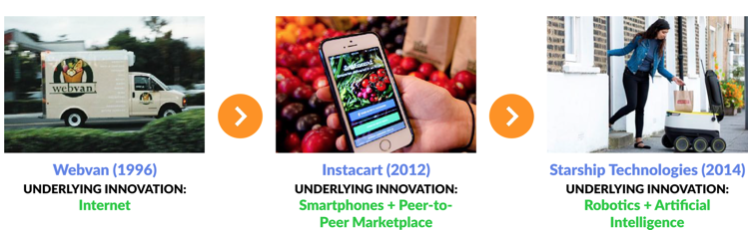

WeтАЩve heard this promise before. In the dot-com bust, on-demand delivery services like Kozmo, Urbanfetch, and Webvan became a symbol of the excess that fueled the crash. The idea then was that the Internet would create efficiencies that offset logistical costs. At its peak (or valley, depending on your perspective), Kozmo was charging $2 per delivery while hemorrhaging money on courier and warehouse expenses (in 1999, Kozmo reported $3.5 million of revenue on $29 million of expenses).

Beginning in 2013, a new crop of on-demand delivery businesses emerged with an eerily similar value proposition, from DoorDash ($721M raised), Instacart ($1B raised) to Postmates ($278M raised), Deliveroo ($860M raised). ChinaтАЩs Ele.me ($2.3B raised). As private financings surged, Benchmark-backed GrubHub recorded a successful IPO in 2014 and is valued at nearly $12 billion today. ChinaтАЩs Ele.me was acquired by Alibaba earlier this year for $9.5 billion.

The key difference is that in 2000, there were only 370 million people on the Internet (roughly 5% of the worldтАЩs population), smartphones were a fantasy, and applications off of a platform had not been invented.

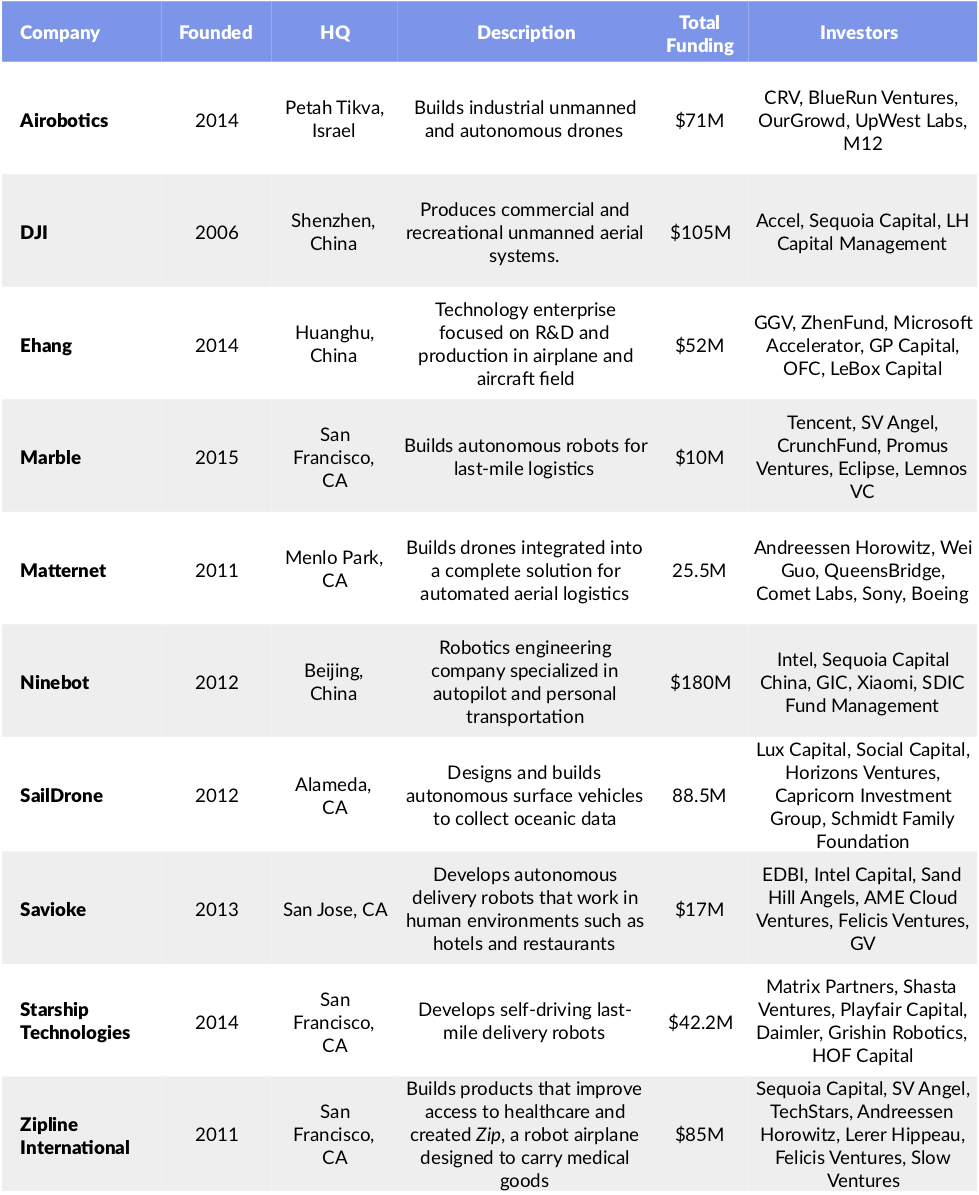

Robo deliveries, which eliminate human labor costs, are the next phase. Starship Technologies, for example, conducts door-to-door deliveries with six-wheeled container robots that now operate globally. Starship started by piloting autonomous delivery programs with DoorDash and Postmates. Today, the company runs pilots on college and corporate campuses and aims to deploy 1,000 delivery bots by the end of this year.

Since it merged with Segway in 2015, Beijing-based Ninebot has been developing and launching transportation robots designed to enable last-mile deliveries. The company raised a $100 million Series C financing in October 2017.

In 2016, San Francisco-based Zipline began using drones to deliver blood from Rwandan blood banks to rural areas for emergency transfusions. Right now, the country struggles to get blood to remote clinics and canтАЩt predict in advance which blood types theyтАЩll need. Furthermore, 75% RwandaтАЩs roads are unpaved and often unusable during the rain season, making them impassable to the vehicles that are deployed to make emergency medical deliveries.

Working with UPS and vaccine distributor Gavi, Zipline is serving 21 medical stations throughout Rwanda delivering blood supplies in less than 30 minutes.

Services + тАЬSocialтАЭ

The first generation of service robots were designed to assist people with repetitive tasks like housecleaning. In 2002, iRobot created the most popular service robot to date, the Roomba vacuum cleaner, which has sold over 15 million units since its launch.

Today, Knightscope robots patrol malls and public areas, coordinating security services and other first responders. Sally the Salad Robot created by Chowbotics, effortlessly creates multi-component salads.

Anki builds entertainment robots that combine the aesthetic of PixarтАЩs WALL-E with the functionality of DisneyтАЩs Baymax. Its Cozmo product, for example, is a toy robot with built-in facial recognition that is able to develop skills over time through play and use.

But whatтАЩs special about Cozmo is its emotional adaptability. It responds to human interactions in very human ways, throwing tantrums and expressing excitement in eerily appropriate settings. Anki recently released CozmoтАЩs SDK, allowing engineers to build programs off its platform, effectively doing for robotics what iOS and Android did for mobile technology.

Over the past two years, weтАЩve seen multiple megarounds of financing completed by companies developing social robots, including UBTECH and Rokid, which raised $840 million and $100 million in 2018 respectively.

Source: Crunchbase, CB Insights, GSV Asset Management