Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

“Work is theatre and every business is a stage.”

— Joseph Pine II & James Gilmore

This week Amazon announced that it will acquire Whole Foods in a transaction valued at $13.7 billion. Pundits quickly framed the deal as a shot in the arm for Amazon’s fledging grocery delivery business, “Amazon Fresh,” which has struggled to gain meaningful traction.

With Whole Foods, Amazon can plug into a network of 460 stores in prime urban locations that could double as distribution nodes. It also acquires a customer base with disposable income, a group of spenders willing to shop at a store dubbed “Whole Paycheck” for its high prices on grocery staples.

In a classic twist of corporate fate, two years ago, Whole Foods co-founder and former CEO John Mackey predicted that Amazon’s foray into groceries would be its “Waterloo,” asking, “What’s the one thing people want? Convenience. You can’t do that with distribution centers and trucks.”

But Amazon isn’t buying Whole Foods for the convenience factor. Jeff Bezos has been driving his digital disruption train over physical commerce for twenty three years, creating the fourth most valuable company in the World by wielding speed, price, and scale with ruthless effect. As Bezos has said, “Your margin is my opportunity.” If Amazon was aiming for convenience, it could have acquired a grocery store network far cheaper. The nearly $14 billion price tag implies a 35x price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple (trailing 12 months), compared to a 14.4 average for the S&P 500 Food Retail index.

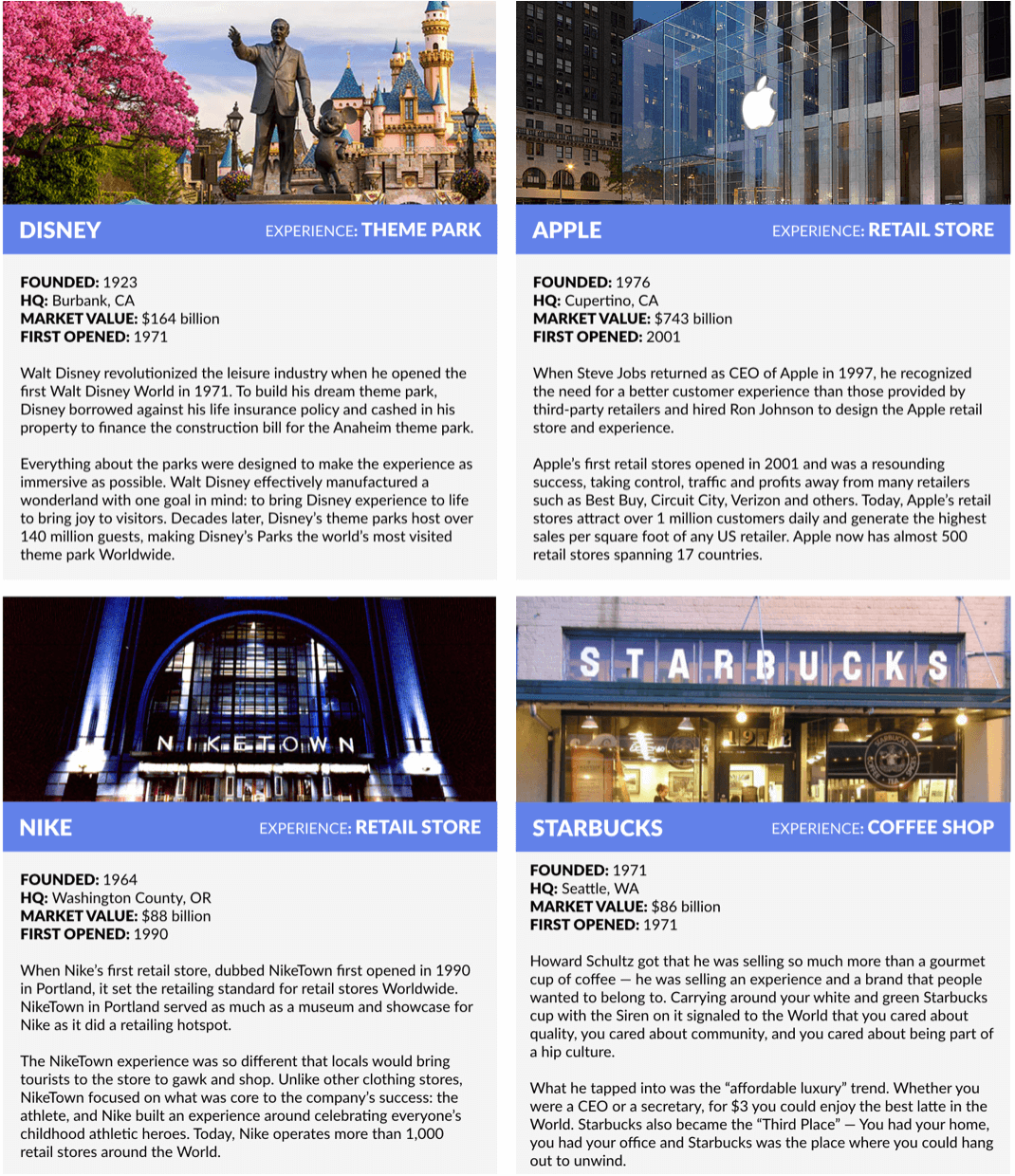

In Whole Foods, Amazon is acquiring a business built on experience. Founded in 1978 in Austin, Texas, Whole Foods is best known for its organic foods, creating a brand based on healthy eating and fresh, local produce. While “grocery stores” like Safeway are soulless, the Whole Foods experience is theater… the theater of artisan wines and craft brewers… the theater of stylized display cases featuring only the freshest fruit or fresh-caught fish… the theater of featuring local farmers, bakers, and cheesemakers.

Sure, Whole Foods will unlock more avenues for Amazon to deliver physical goods to your doorstep. But it also makes Amazon a relevant player in a megatrend called the “Experience Economy” and that might be the most transformational aspect of the acquisition.

THE EXPERIENCE ECONOMY

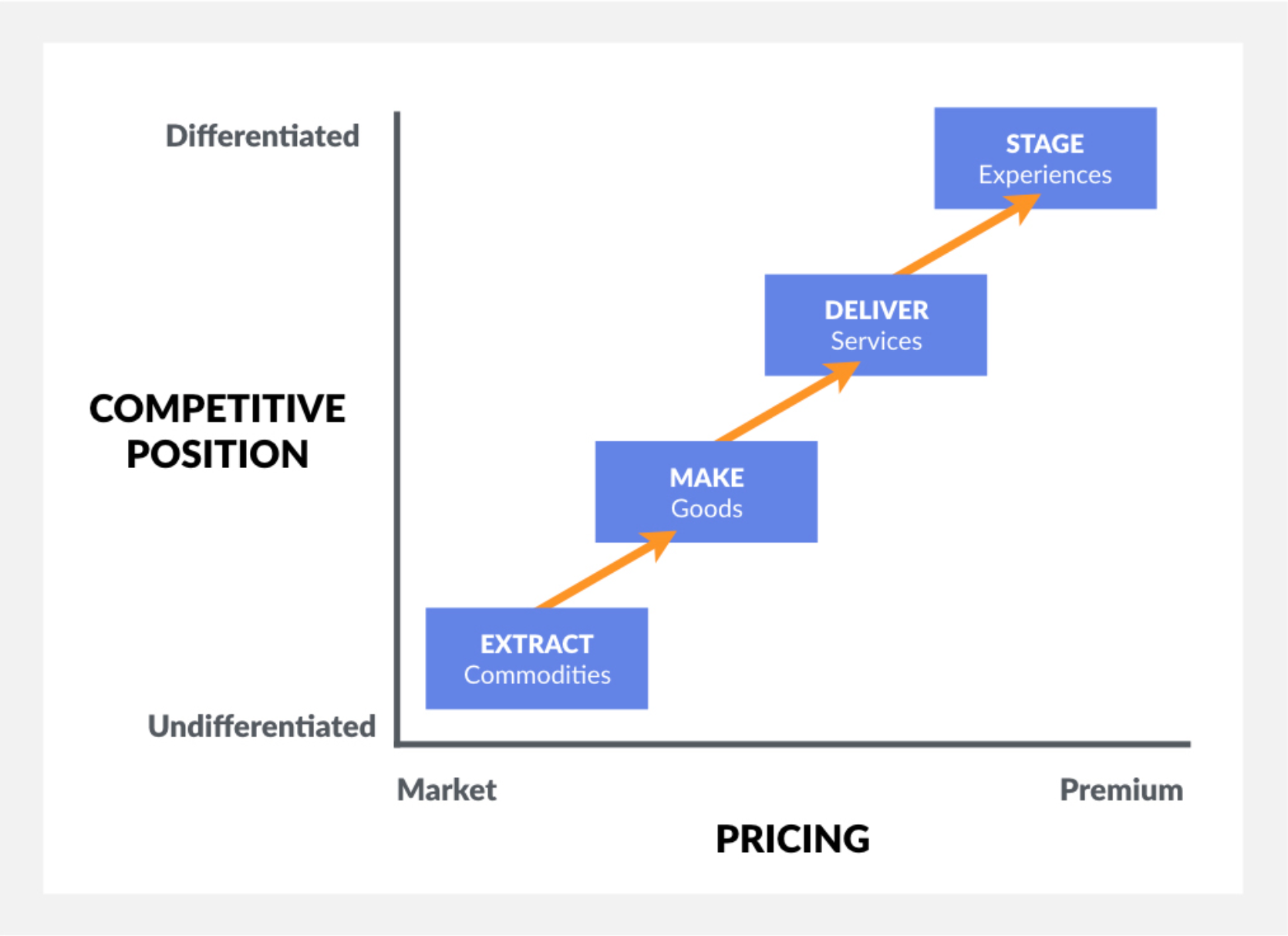

In their 1999 book The Experience Economy, Joseph Pine and James Gilmore argue that the entire history of global economic progress can be summarized in the evolution of the birthday cake:

As a vestige of the agrarian economy, mothers made birthday cakes from scratch, mixing farm commodities (flour, sugar, butter, and eggs) that together cost mere dimes. As the goods-based industrial economy advanced, moms paid a dollar or two to Betty Crocker for premixed ingredients. Later, when the service economy took hold, busy parents ordered cakes from the bakery or grocery store, which, at $10 or $15, cost ten times as much as the packaged ingredients. Now, in the time-starved 1990s, parents neither make the birthday cake nor even throw the party. Instead, they spend $100 or more to “outsource” the entire event to… [a] business that stages a memorable event for the kids—and often throws in the cake for free.

An “Experience” — a memorable event intentionally created for a consumer — is a distinct economic offering that has become more valuable as goods and services are commoditized.

In the 1960s, IBM’s slogan was “IBM Means Service,” and the computer manufacturer offered a broad range of services for customers that bought its hardware — from programming code to planning facilities and repairing devices.

Eventually, as hardware became commoditized, IBM could no longer afford to give its lavish services away for free. Services had inadvertently become the company’s most valuable offering. By 2000, IBM’s business had effectively flipped. It was buying its clients hardware to secure lucrative contracts to manage information systems.

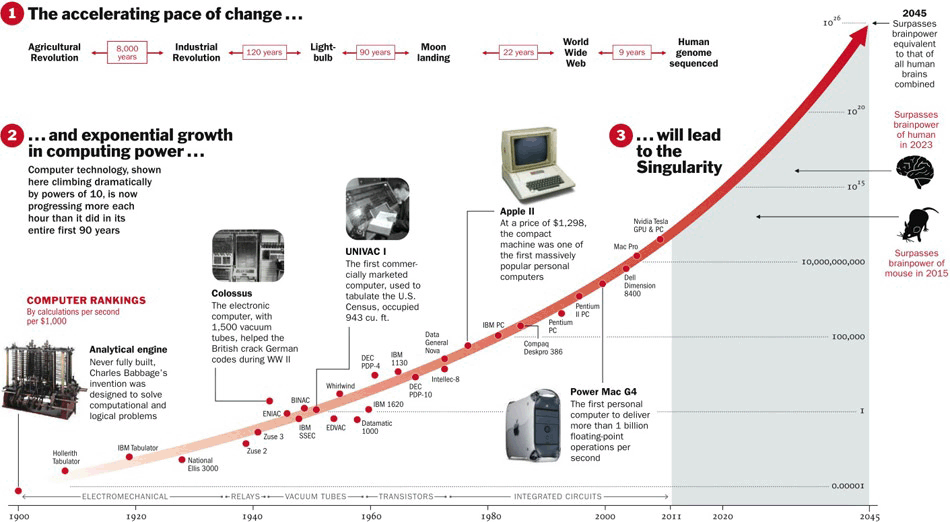

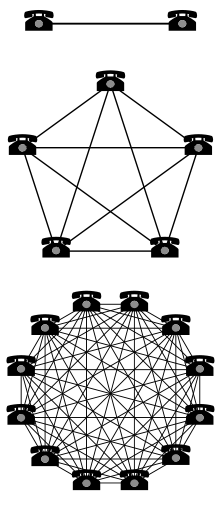

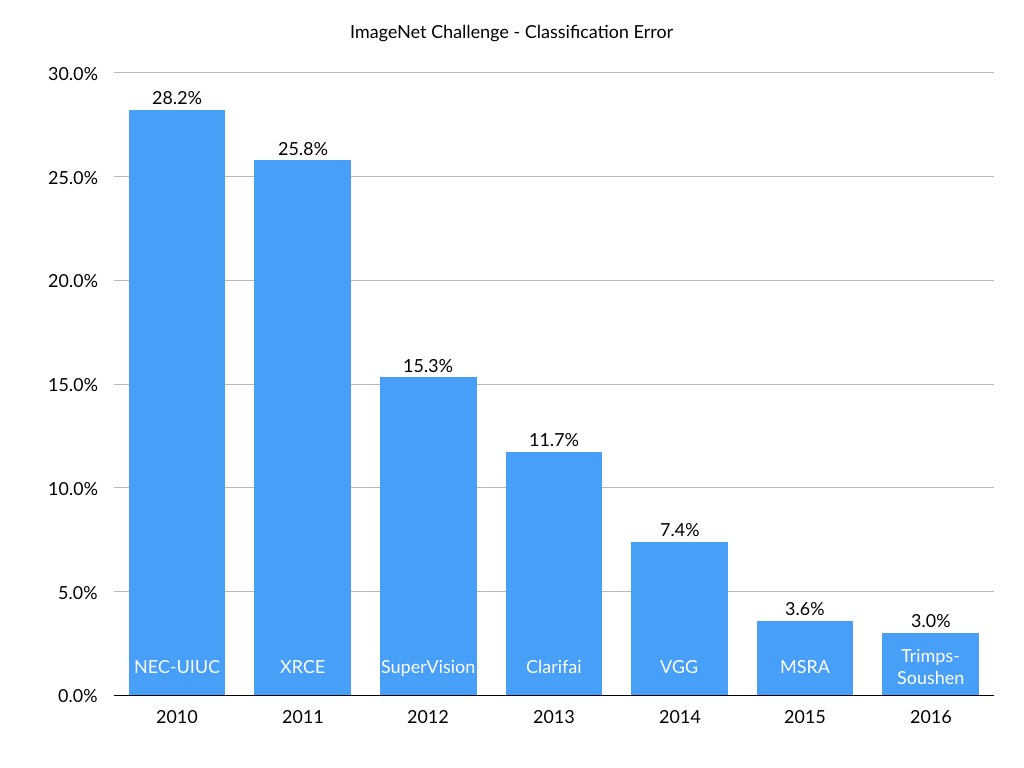

Pine and Gilmore published their book in 1999, five years after Marc Andreessen co-founded Netscape, creating the Internet as we know it. Over the next 23 years — a period where Moore’s Law drove down the cost of computing, data storage, and broadband by 99% — internet access grew from 13.5 million people to 3.4 billion and smartphones went from science fiction to 2.6 billion users with 258 billion app downloads to date.

In this interval, the Internet, and later smartphones, have transformed the way services are designed and delivered, from retail (e.g. Amazon and eBay) to transportation, (e.g. Uber and Lyft) to communication (e.g. Facebook and Snapchat). (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Lyft and Snapchat)

As digital services with massive scale have created broad efficiencies and commoditization, the power of the Experience Economy is more relevant than it ever has been. It is the next competitive frontier.

Last year, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky unveiled a service called “Trips,” which offers much more than a place to sleep. It’s a collection of over 500 private tours and tailored activities — from art classes to workouts and nightlife — available through the network.

Airbnb is not content to be a room broker. It’s going all in on experience.

KEY ELEMENTS OF AN EXPERIENCE ECONOMY

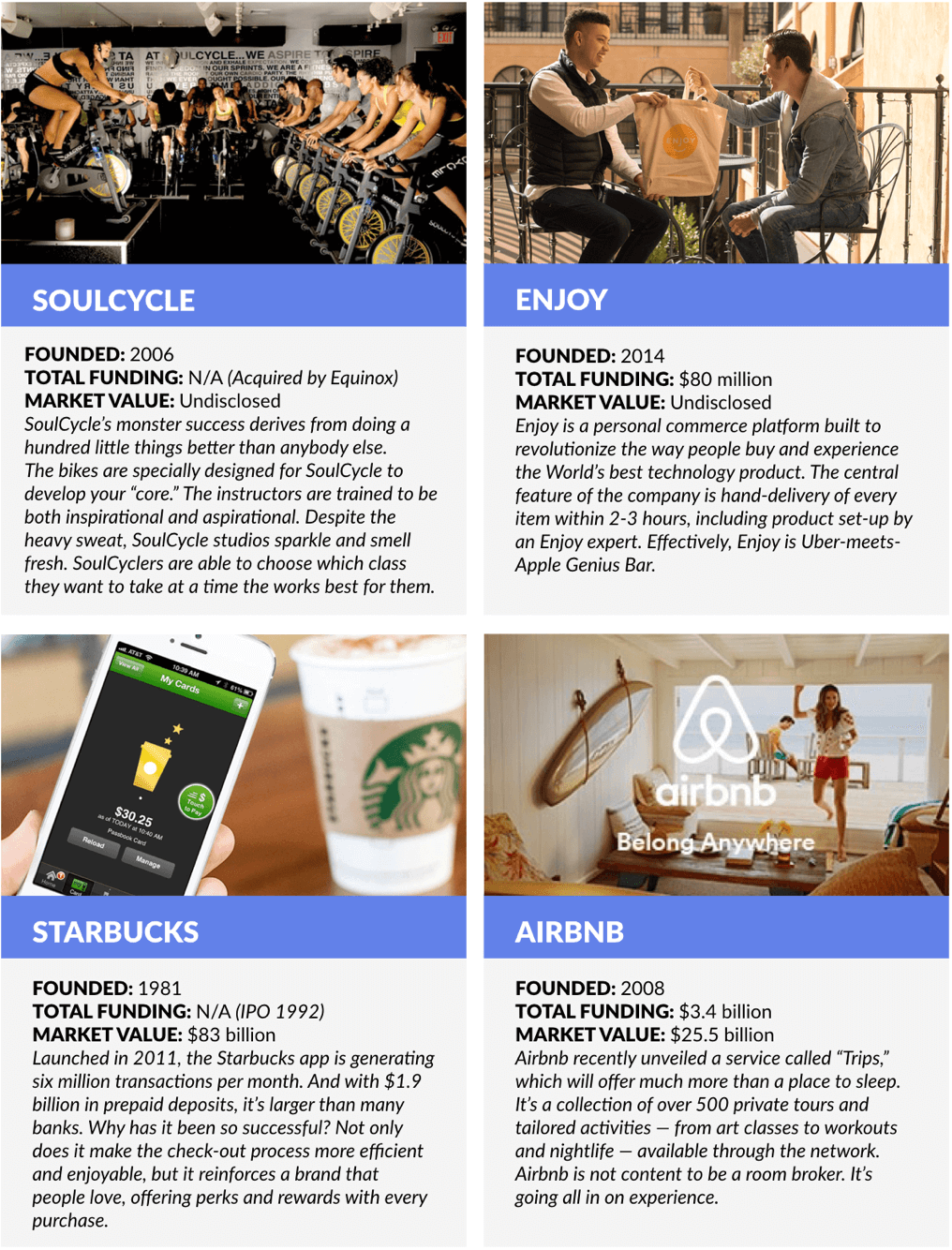

Seamless Integration: Digital Commerce + Delightful Experience

If you look at the world of physical stores, many compete on service — the customer experience — not just efficiency. For every Best Buy, there is an Apple store. For every Target, there’s a Nordstrom. The next wave of digital commerce will bring a renewed focus on combining efficiency with a superior personal experience.

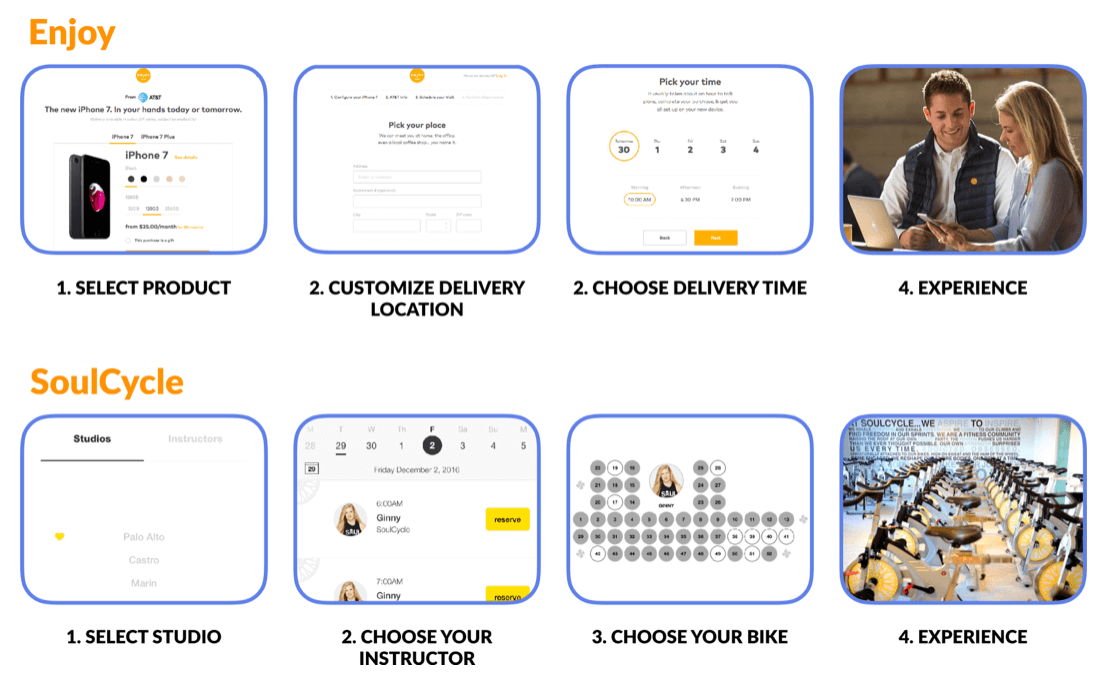

Enjoy, co-founded by former Apple retail head Ron Johnson, is at the forefront of this trend. It’s a personal commerce platform built to revolutionize the way people buy and experience the World’s best technology products — from smartphones to wireless sound-systems and drones. The central feature of the company is hand-delivery of every item within 2-3 hours, including product set-up by an Enjoy expert. Effectively, Enjoy is Lyft-meets-Apple Genius Bar. (Disclosure: GSV owns share in Enjoy and Lyft)

The magic is in the experience Enjoy delivers. Efficient, on-demand delivery is table stakes. Enjoy experts meet customers at a time and place of their choosing, arriving early 97% of the time. Delivery is free and the product prices are the same or less than Amazon, Best Buy, or the Apple store. Enjoy’s NPS (Net Promoter Score) is the highest we’ve seen anywhere, indicating a customer who’s not only satisfied, but who’s an evangelist.

How does it work? Enjoy doesn’t build stores. It hires great people. Enjoy can deploy a team of highly trained, engaging product experts a lot less expensively than building a physical storefront. Effectively, it works off the same margins as a physical store, but with a different model. Ultimately, Enjoy is part of a trend that transcends the delivery market. It is focused on creating a delightful experience for people that make digital purchases. In this respect, popular, emerging consumer businesses like SoulCycle are kindred spirits.

There is nothing about what SoulCycle does that can be patented. The casual observer might even mistake it for a “spinning class.” But when you study SoulCycle, you realize that its monster success derives from doing a hundred little things better than anybody else.

First, SoulCycle is a digital commerce platform. You go on your phone. You pick your class, your bike, your instructor, and your session time. Mobile payments are fully integrated.

And then you show up and have a delightful experience. The bikes are specially designed for SoulCycle to develop your “core.” The program emphasizes every muscle in your body, so that after 45 minutes, you’re wiped. The instructors are trained to be both inspirational and aspirational. The music is perfectly choreographed. Despite the heavy sweat, SoulCycle studios sparkle and smell fresh. And there is plenty of cool SoulCycle swag, so you can proudly display that you’re a member of the tribe.

Like Enjoy, SoulCycle starts digitally, and ends with an experience you love. We see a new generation of businesses emerging that are creating advantages through both mobile and physical experiences.

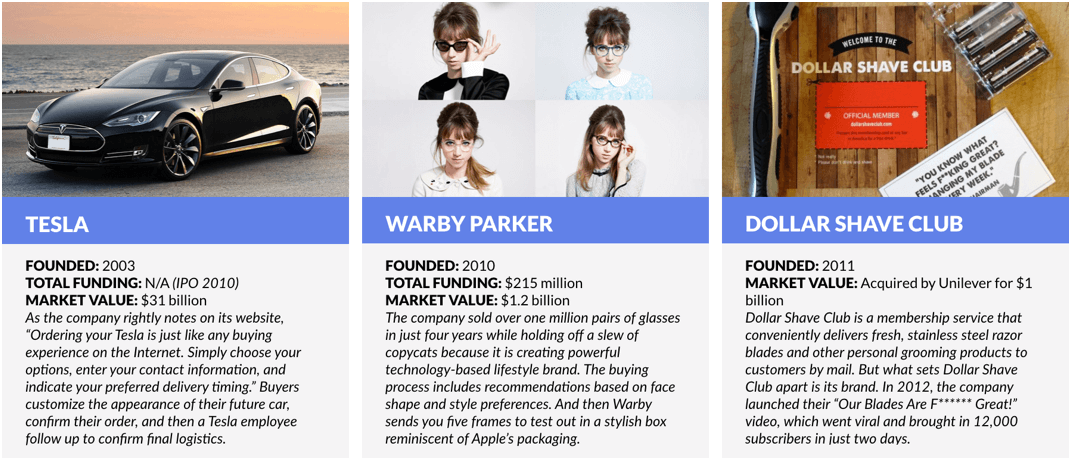

Similarly, forward-thinking retailers are unlocking the power of a delightful customer experience around the digital purchasing process itself. As Tesla notes on its website, “Ordering your Tesla is just like any buying experience on the Internet. Simply choose your options, enter your contact information, and indicate your preferred delivery timing.”

Goodbye car dealerships and awkward, high-pressure sales experiences.

The Tesla ordering process begins in a virtual “Design Studio” where buyers customize the appearance of their future car and select various options. Price changes are transparent. Once the order is confirmed, a Tesla “Experience Specialist” follows up to answer any lingering questions you may have, as well as to discuss financing options, trading in your old car, installing charging equipment, and delivery day logistics.

Warby Parker has taken a relatively expensive product — glasses — cut out the middle men (distributors and licensors), and sold it directly to consumers online at a discount to traditional retailers. For $95, you can get a cool pair of glasses, including prescription lenses and shipping. And for every pair purchased, Warby Parker donates a pair to someone in need.

But the company has sold over one million pairs of glasses in just four years while holding off a slew of copycats because it is creating a powerful technology-based experience. The buying process includes recommendations based on face shape and style preferences. And then Warby sends you five frames to test out in a stylish box reminiscent of Apple’s packaging. And if you still need help deciding, you can post a picture of yourself using #warbyhometryon and the company will give you feedback. In May 2017, Warby Parker launched an app that lets users to check their prescription at home, without visiting a doctor or an optician.

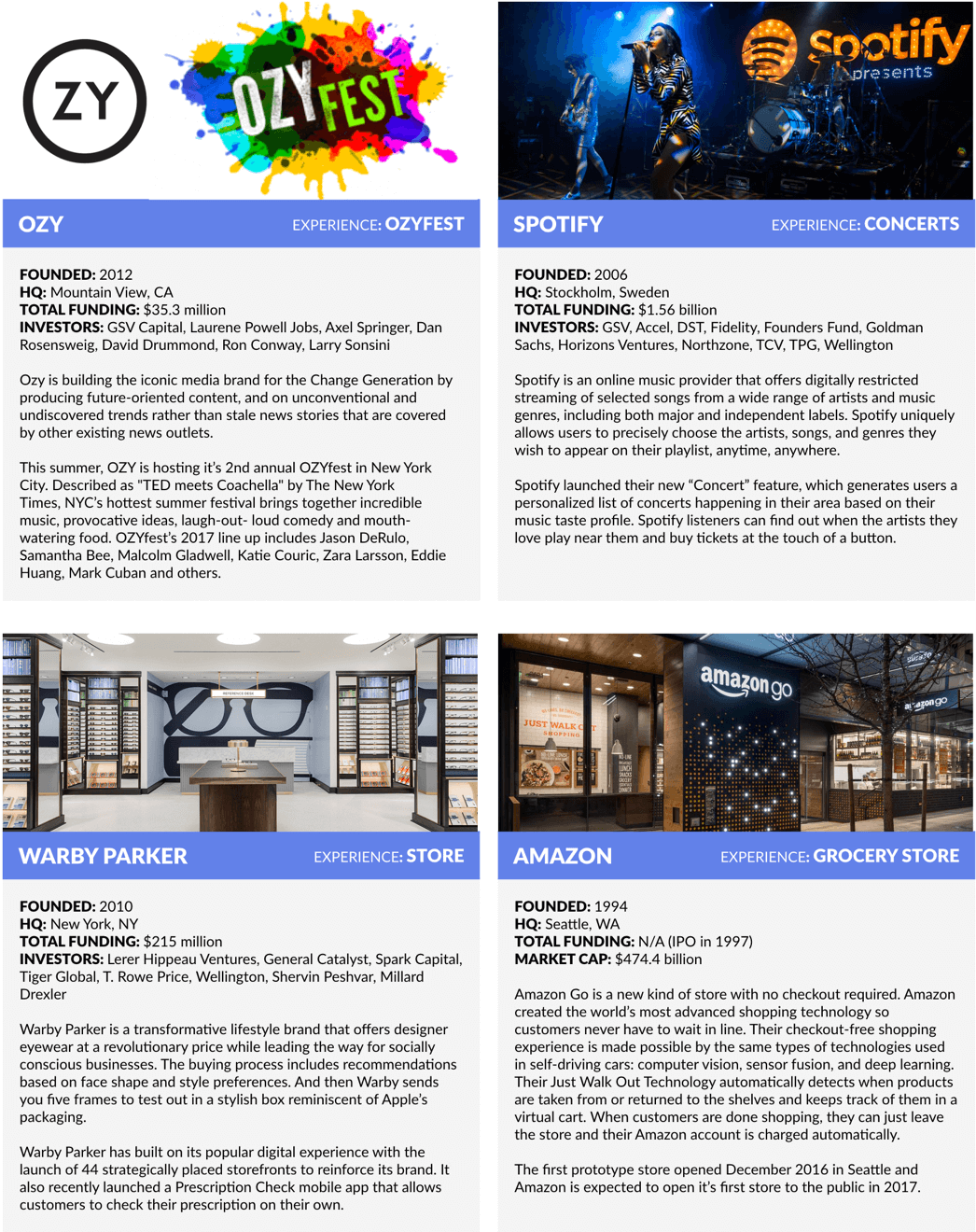

From Digital to Physical

While Warby Parker is creating a superior digital experience, the company plans to open 25 retail locations in 2017, which will bring its total store count to 70. As co-founder and co–CEO Neil Blumenthal has observed, “I don’t think retail is dead. Mediocre retail experiences are dead.”

This highlights another key trend in the Experience Economy. Physical locations are an important platform to create an unique customer experience, and accordingly, brands like Warby Parker that were “born” on the Internet are turning the retail model upside-down by opening physical storefronts. Bonobos, the popular online clothing retailer that was acquired last week by Walmart for$310 million, has followed the same strategy.

”How” vs. “What”

In his signature book How, Dov Seidman makes the case that in an era of digital connectivity, increasing transparency, and global interdependence, “how” we do anything means everything.

There are three fundamental ways to drive human behavior. You can coerce, incentivize, or inspire. Coercion and incentives rely on external rewards (Carrots) and punishments (Sticks). But in an interconnected world, the limitations of Carrots and Sticks are quickly becoming clear. Rules cannot keep pace with technology innovation — a challenge that China has grappled with as it seeks to limit the ability of social networks to amplify political unrest.

On the other end of the spectrum, the return on incentives has declined as increasing connectivity and access to information enable people to find better “deals” elsewhere. It’s getting harder to buy loyalty.

Inspiration, Seidman argues, is the new difference-maker. Accordingly, a company’s ability to define and adhere to a sustainable value set is the key to creating commercial and strategic advantage.

According to research from PR powerhouse Edelman, U.S. consumers report that when quality and price are a wash in competing products, a company’s “social purpose” is the most important factor in their purchase decision. Nearly 44% of people were even willing to pay a premium for the products of companies that support a “good cause” and 62% indicate that they will not buy a brand if it fails to meet societal obligations.

Uber’s recent series of high-profile public missteps — culminating in the departure of CEO Travis Kalanick — coupled with Lyft’s gains in competitive market share is a case in point.

In a recent report published by Quartz, the number of U.S. consumers who said they would consider taking Lyft jumped to 9.6% in Q1 2017, up from 5.6% in Q4 2016. Uber fell to 14% from 18% in the same period. In January, Lyft announced that it delivered 163 million rides in 2016, more than tripling its 2015 total. It has launched in over 100 new cities in 2017 to date, and in March the company reported that its growth was accelerating in every market across the country.

While Uber has created a culture and brand focused on World domination, Lyft’s competitive advantage is its mission and its emphasis on creating a unique experience. Co-founders Logan Green (CEO) and John Zimmer (President) created the company with the goal to reduce traffic congestion and pollution while improving the quality of urban life.

Zimmer — who not coincidentally graduated top of his class from Cornell University’s School of Hotel Administration — was the brainchild behind a brand that encouraged passengers to sit in the front seat and “fist bump” drivers at the beginning of each ride. Lyft has always been about more than getting to your destination quickly, which is table stakes. A recent ad campaign sums up the contrast with Uber perfectly.

Mind, Body, Soul

A related megatrend creating huge opportunities is a phenomenon we call “Mind, Body, Soul” — businesses with a value proposition and customer experience at the intersection of healthy living and mental and spiritual well-being. Here again, SoulCycle is a leader, combining a fitness experience with the mindfulness of meditation in a consumer brand people love.

Aspiration, a digital financial services platform launched in 2013, won’t make you fit, but it’s a bank with a soul. It donates 10% of revenue to economic development charities and has an entire section of its website devoted to financial education. But what truly differentiates Aspiration from its peers is a “Pay What is Fair” model. Investors and account holders can pay the company as much or as little as they want—even if that amount is zero. (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Aspiration)

Co-Founder and CEO Andrei Cherny — a former speech writer for President Bill Clinton (one of the youngest in history), Naval Reserve Officer, and longtime consumer advocate — has observed that Aspiration is “taking the entire business model of Wall Street and turning it on its head.” He’s making a bet that consumers will choose a bank that enables them to “do well” while “doing good.” It helps that Aspiration has gone directly to digital without physical infrastructure, meaning that the marginal cost of serving each customer is low. Interestingly, the company has found that its customers tend to pay the same or more than the fees for comparable services from traditional financial services providers. Over 90% of users pay a fee.

In April 2017, Aspiration launched Aspiration Impact Measurement, or “AIM,” a feature that enables its account holders to determine a “Sustainability Score” for their purchases. Each month, Aspiration’s mobile banking app tracks spending patterns and offers a social impact report based on purchases from different companies. The first key metric is how a company treats its employees. The second is how it treats the planet. “In this day and age, money talks,” Cherny observed when AIM was announced. “Imagine weaponizing that consumer sentiment and putting it in your pocket.”

WHAT’S NEXT

Augmented and virtual reality will lead to a new crop of “experience” businesses that will use the technology to bring virtual experiences into the real world. When Pokemon Go launched last Summer, it was the starting gun that signaled that Virtual Reality was here to stay. In its first two months, Pokemon Go was downloaded 500 million times and was the fastest game to reach $500 million in revenue.

The game — which allows you to capture, train, and trade virtual creatures on your smartphone that “appear” in the real world — has quickly put our physical and digital realities in the blender. It has sent people into streets and parks, onto beaches, and even into cemeteries, in pursuit of Pokémon. You can find “Poke Stops” — hubs where the creatures abound — at the 9/11 memorial in New York City, in schools and churches, and everywhere in between. In O’Fallon, Missouri, a group of teenagers used the app to carry out armed robberies, employing the game’s geolocation feature to anticipate the location of unwitting victims.

As the CEO of the game’s creator, Niantic Labs, observed in an interview with CB Insights, “There’s of course this fantastical Pokémon element, but really it’s enhancing your experience of going out for walk or doing something with friends. I think AR is something that can be with us all the time, that we can use during the day and in everything, from commerce to entertainment to social interactions.”

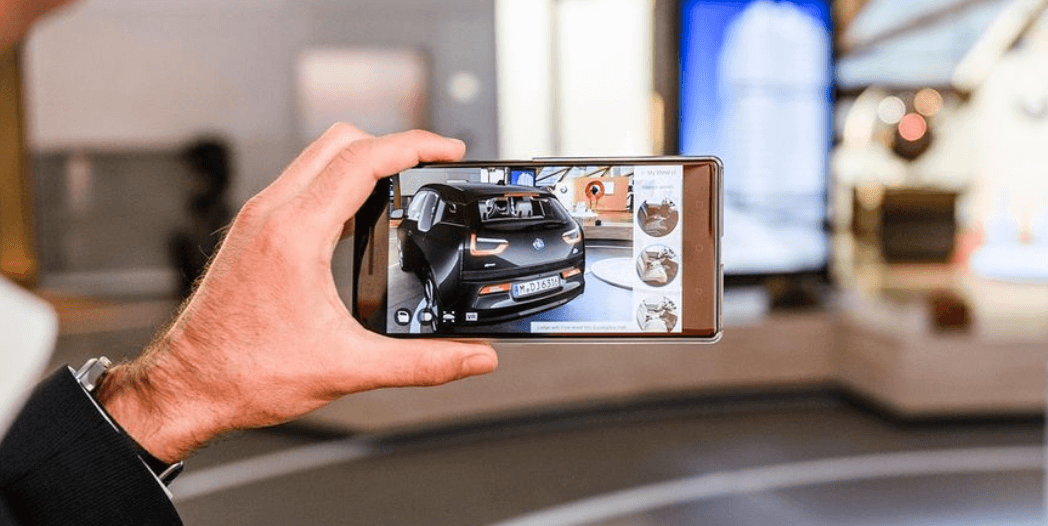

Physical retailers are already venturing in the VR/AR realm, seeking to use the technology to enhance the retail experience. This January, Google announced partnerships with Gap and BMW, deploying its app Tango to create virtual showrooms.

With BMW, Google is developing an app that displays BMW vehicles on smartphone screens, allowing shoppers to walk around superimposed vehicles, placing it to look life-size at their homes, and also conceptualize what their new vehicle could look like in different colors and trims. To some users who demoed the app, the virtual car on a phone screen was so lifelike that users ducked and lifted their legs to “step” inside the vehicle.

Amazon is also reportedly looking to use augmented reality technology to sell furniture and appliances, allowing people to see how sofas, desks, ovens and more look in their homes before they even purchase the item.