Market Snapshot

| Indices | Week | YTD |

|---|

Every crowd has a silver lining.

― P. T. BARNUM

Making sushi is an art, and experience is everything.

— NOBU MATSUHISA

Good judgement is the result of experience and experience the result of bad judgement.

― Mark Twain

Anonymous.

It used to be that you had to wait all year for the Circus to come to town. Now, courtesy of Twitter, cable news, and even The Gray Lady, the clowns, dwarfs, and Snake Men stay in Washington D.C. and can be witnessed in the comfort of our own homes.

The one-two punch of Bob Woodward’s “Fear” and Anonymous’ Op/Ed shockingly (I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on in here!) depicted a chaotic White House with a President that needed to be protected from himself… and the Country. Russian collusion now seems a stretch, but Beltway collusion is a layup. Meanwhile, the economy — oblivious to the activity in the three-ring circus — hummed along creating more than 200,000 new jobs including in the missing and presumed dead manufacturing sector.

At the same time, big bad tech was being water boarded by Congress for its aiding and abetting foreign enemies in our elections. Messrs. Dorsey and Mademoiselle Sandberg did their best to protest but ultimately waved the white flag… even though the allegations were non-sensical. Nonetheless, Twitter and Facebook shares sank to yearly lows and were a catalyst for NASDAQ and growth stocks to be slammed with NASDAQ dropping 2.6%.

Even with the overall negative sentiment for big tech and growth, Amazon continued its upward march and became the second company in the World after Apple to exceed a trillion dollar market cap. (Interestingly, Amazon’s Chinese rival Alibaba made it known that its founder Jack Ma was looking to move to his next chapter, which is to focus on education issues.)

Last year, Amazon acquired Whole Foods in a transaction valued at $13.7 billion. Pundits quickly framed the deal as a shot in the arm for Amazon’s fledging grocery delivery business, “Amazon Fresh,” which has struggled to gain meaningful traction.

With Whole Foods, Amazon can plug into a network of 460 stores in prime urban locations that could double as distribution nodes. It also acquires a customer base with disposable income, a group of spenders willing to shop at a store dubbed “Whole Paycheck” for its high prices on grocery staples.

In a classic twist of corporate fate, two years ago, Whole Foods co-founder and former CEO John Mackey predicted that Amazon’s foray into groceries would be its “Waterloo,” asking, “What’s the one thing people want? Convenience. You can’t do that with distribution centers and trucks.”

Jeff Bezos would beg to differ. Approximately 50% of Americans live within 20 miles of an Amazon warehouse, up from 5% in 2015. Over 34% of US households are within five miles of a Whole Foods. You can create a lot of convenience with distribution centers and trucks if you have enough of them in the right places.

But Amazon didn’t buy Whole Foods for the convenience factor. Jeff Bezos has been driving his digital disruption train over physical commerce for twenty four years, creating the second most valuable company in the world by wielding speed, price, and scale with ruthless effect. As Bezos has said, “Your margin is my opportunity.” If Amazon was aiming for convenience, it could have acquired a grocery store network far cheaper. The nearly $14 billion price tag implied a 32x price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple at the time (trailing 12 months), compared to a 14.4 average for the S&P 500 Food Retail index.

In Whole Foods, Amazon acquired a business built on experience. Founded in 1978 in Austin, Texas, Whole Foods is best known for its organic foods, creating a brand based on healthy eating and fresh, local produce.

While “grocery stores” like Safeway are soulless, the Whole Foods experience is theater… the theater of artisan wines and craft brewers… the theater of stylized display cases featuring only the freshest fruit or line-caught fish… the theater of featuring local farmers, bakers, and cheesemakers.

Sure, Whole Foods unlocks more avenues for Amazon to deliver physical goods to your doorstep. But it also has made Amazon a relevant player in a megatrend called the “Experience Economy” and that might be the most transformational aspect of the acquisition.

THE EXPERIENCE ECONOMY

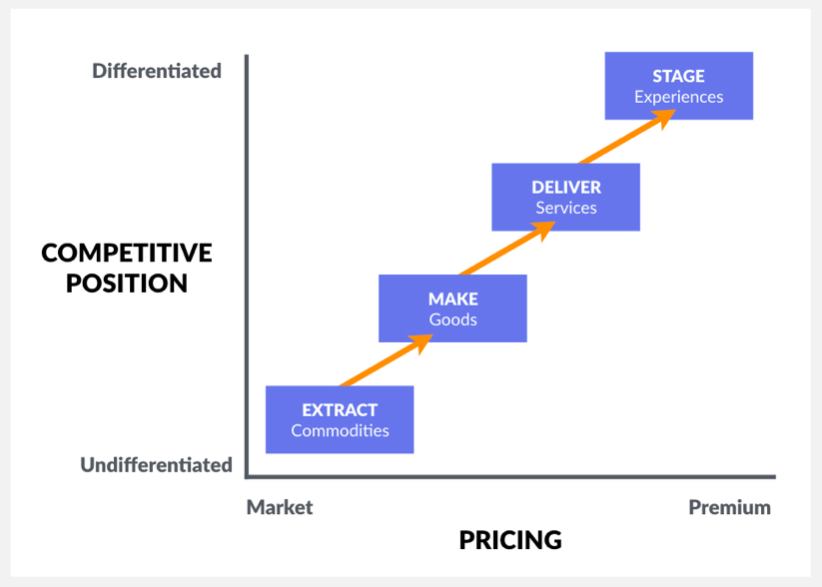

In their 1999 book The Experience Economy, Joseph Pine and James Gilmore argue that the entire history of global economic progress can be summarized in the evolution of the birthday cake:

As a vestige of the agrarian economy, mothers made birthday cakes from scratch, mixing farm commodities (flour, sugar, butter, and eggs) that together cost mere dimes. As the goods-based industrial economy advanced, moms paid a dollar or two to Betty Crocker for premixed ingredients. Later, when the service economy took hold, busy parents ordered cakes from the bakery or grocery store, which, at $10 or $15, cost ten times as much as the packaged ingredients. Now, in the time-starved 1990s, parents neither make the birthday cake nor even throw the party. Instead, they spend $100 or more to “outsource” the entire event to… [a] business that stages a memorable event for the kids—and often throws in the cake for free.

An “Experience” — a memorable event intentionally created for a consumer — is a distinct economic offering that has become more valuable as goods and services are commoditized.

In the 1960s, IBM’s slogan was “IBM Means Service,” and the computer manufacturer offered a broad range of services for customers that bought its hardware — from programming code to planning facilities and repairing devices.

Eventually, as hardware became commoditized, IBM could no longer afford to give its lavish services away for free. Services had inadvertently become the company’s most valuable offering. By 2000, IBM’s business had effectively flipped. It was buying its clients hardware to secure lucrative contracts to manage information systems.

Pine and Gilmore published their book in 1999, five years after Marc Andreessen co-founded Netscape, creating the Internet as we know it. Over the next 23 years — a period where Moore’s Law drove down the cost of computing, data storage, and broadband by 99% — internet access grew from 13.5 million people to 3.4 billion and smartphones went from science fiction to over 2.6 billion users with nearly 300 billion app downloads to date.

In this interval, the Internet, and later smartphones, have transformed the way services are designed and delivered, from retail (e.g. Amazon and eBay) to transportation, (e.g. Uber and Lyft) to communication (e.g. Facebook and Snap). (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in Lyft)

As digital services with massive scale have created broad efficiencies and commoditization, the power of the Experience Economy is more relevant than it ever has been. It is the next competitive frontier.

Ironically, a huge driver of this trend is the Millennial generation. Born “digital first,” this group will command over $4 trillion of spending power by 2030. This generation uniquely gravitates towards experiences. According to a survey conduced by Eventbrite, more than three in four American millennials would rather spend money on a desirable experience or event than buy a desirable object.

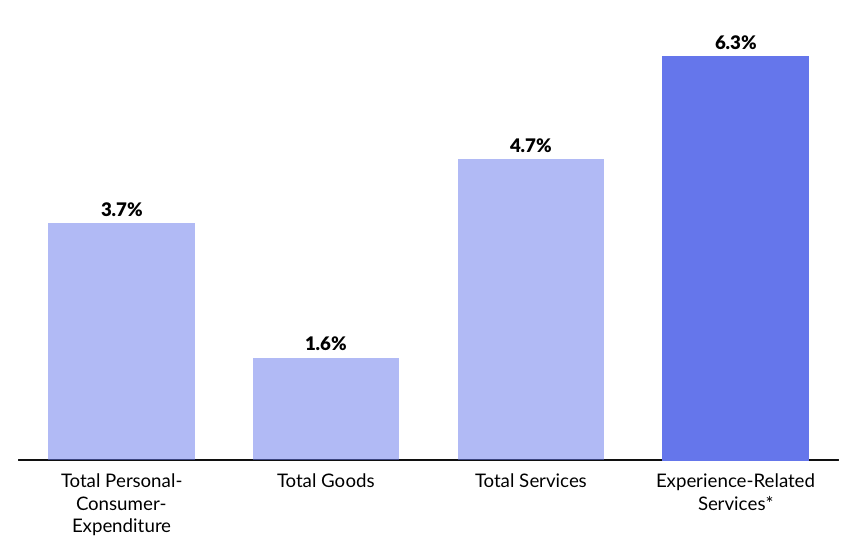

But this is a broader phenomenon. Over the past few years, McKinsey reports that personal-consumption expenditures on experiential services — including attending spectator events, visiting amusement parks, eating at restaurants, and traveling — have grown more than 1.5x faster than overall personal-consumption spending and nearly 4.0x faster than expenditures on goods.

All in all, market research provider Euromonitor forecasts that the experience economy will surpass $8.2 trillion in economic activity by 2028.

Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, McKinsey

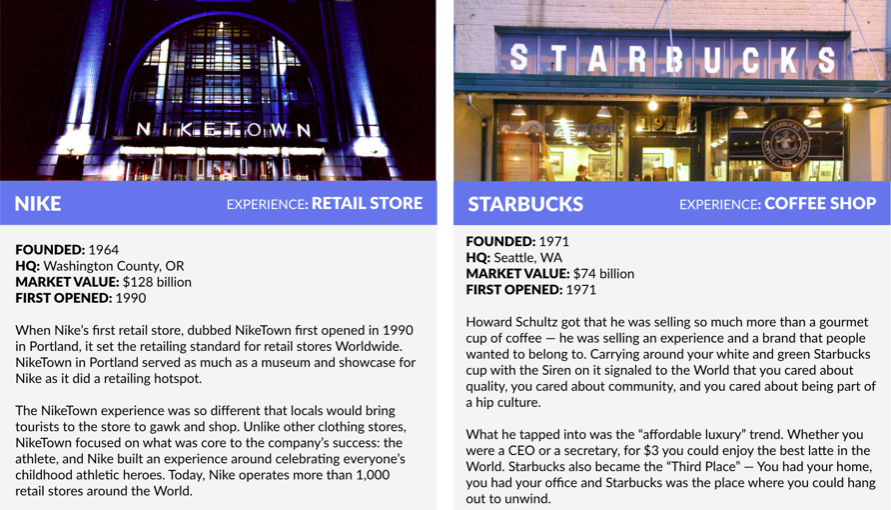

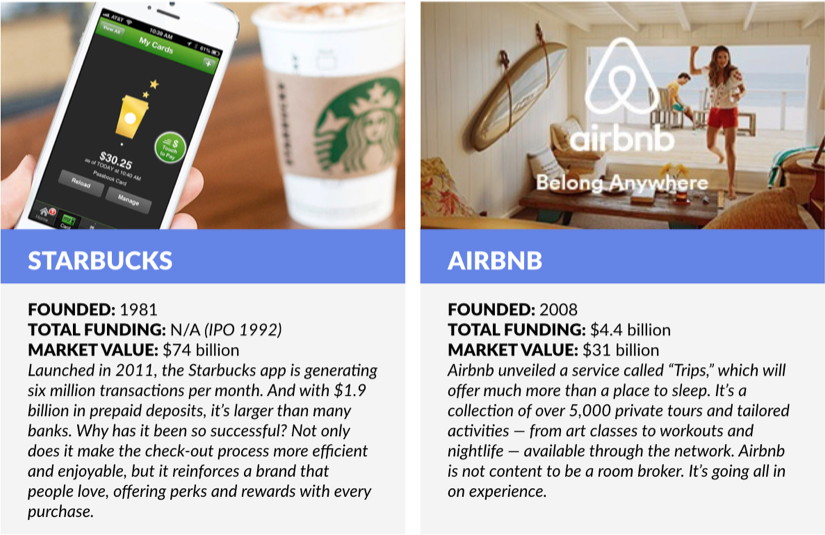

Former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz recently observed that any retailer who is, “going to win in this new environment must become an experiential destination.”

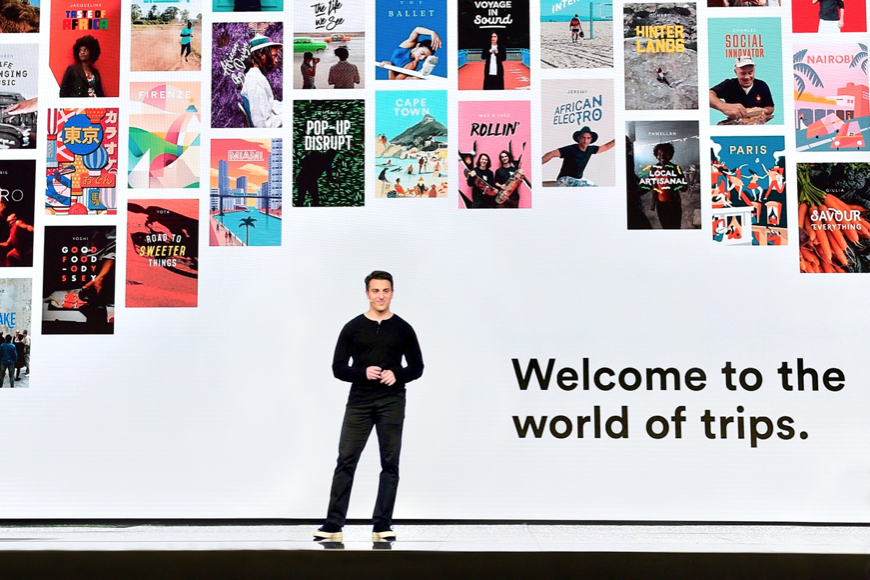

In 2016, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky unveiled a service called “Experiences,” signaling that his company was not simply content to be a technology platform or a home rental marketplace. Airbnb is in the experiential destination business.

The company’s first product launch since its initial product, Airbnb Experiences is a collection of private tours and tailored activities — from wine tasting in California to kimono making in Tokyo and guided meditation in Paris — available through the network.

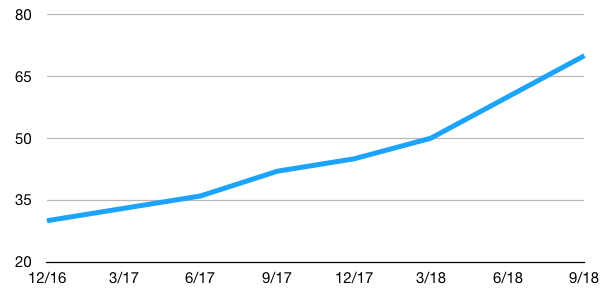

Today, the platform offers more than 5,000 experiences in 60+ cities worldwide. A year after announcing the product, weekly Experience bookings were up over 2,000% and the number of active Experiences was up 500%.

Source: Airbnb

Brian Chesky has observed that the global tourism market is worth more than $2.5 trillion — five times larger tan the advertising industry. According to Reuters, Airbnb Experiences is on track to surpass one million bookings by the end of 2018 and is expected to be profitable by the end of 2019. Earlier this year, the company announced that it was investing heavily to expand the Experiences product, aiming to reach to 200 U.S. cities by the end of this year.

KEY ELEMENTS OF AN EXPERIENCE ECONOMY

Seamless Integration: Digital Commerce + Delightful Experience

If you look at the world of physical stores, many compete on service — the customer experience — not just efficiency. For every Best Buy, there is an Apple store. For every Target, there’s a Nordstrom. The next wave of digital commerce will bring a renewed focus on combining efficiency with a superior personal experience.

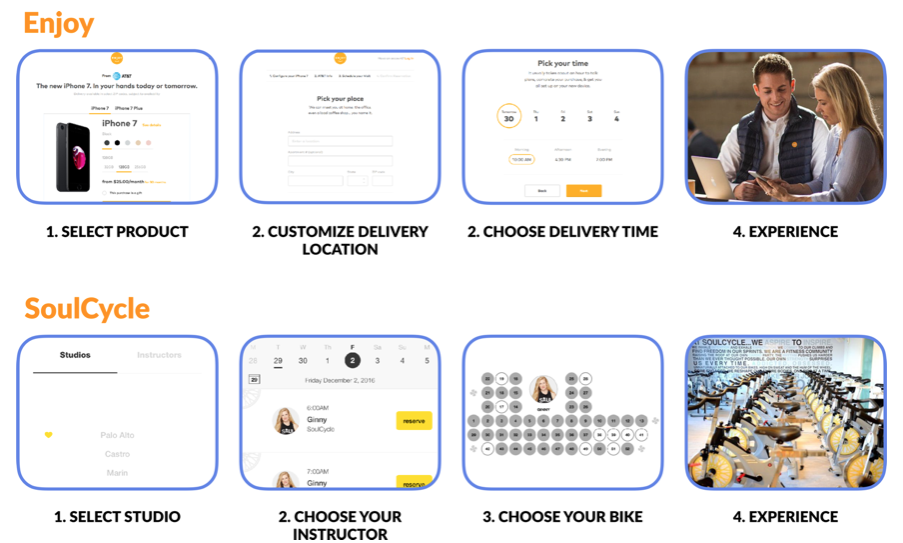

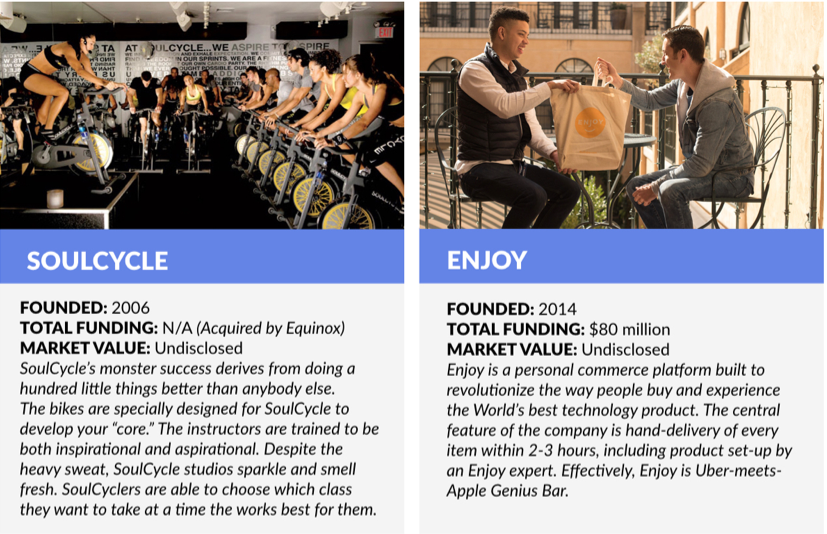

Enjoy, co-founded by former Apple retail head Ron Johnson, is at the forefront of this trend. It’s a personal commerce platform built to revolutionize the way people buy and experience the World’s best technology products — from smartphones to wireless sound-systems and drones. The central feature of the company is hand-delivery of every item within 2-3 hours, including product set-up by an Enjoy expert. Effectively, Enjoy is Lyft-meets-Apple Genius Bar. (Disclosure: GSV owns share in Enjoy and Lyft)

The magic is in the experience Enjoy delivers. Efficient, on-demand delivery is table stakes. Enjoy experts meet customers at a time and place of their choosing, arriving early 97% of the time. Delivery is free and the product prices are the same or less than Amazon, Best Buy, or the Apple store. Enjoy’s NPS (Net Promoter Score) is the highest we’ve seen anywhere, indicating a customer who’s not only satisfied, but who’s an evangelist.

How does it work? Enjoy doesn’t build stores. It hires great people. Enjoy can deploy a team of highly trained, engaging product experts a lot less expensively than building a physical storefront. Effectively, it works off the same margins as a physical store, but with a different model. Ultimately, Enjoy is part of a trend that transcends the delivery market. It is focused on creating a delightful experience for people that make digital purchases. In this respect, popular, emerging consumer businesses like SoulCycle are kindred spirits.

There is nothing about what SoulCycle does that can be patented. The casual observer might even mistake it for a “spinning class.” But when you study SoulCycle, you realize that its monster success derives from doing a hundred little things better than anybody else.

First, SoulCycle is a digital commerce platform. You go on your phone. You pick your class, your bike, your instructor, and your session time. Mobile payments are fully integrated.

And then you show up and have a delightful experience. The bikes are specially designed for SoulCycle to develop your “core.” The program emphasizes every muscle in your body, so that after 45 minutes, you’re wiped. The instructors are trained to be both inspirational and aspirational. The music is perfectly choreographed. Despite the heavy sweat, SoulCycle studios sparkle and smell fresh. And there is plenty of cool SoulCycle swag, so you can proudly display that you’re a member of the tribe.

Like Enjoy, SoulCycle starts digitally, and ends with an experience you love. We see a new generation of businesses emerging that are creating advantages through both mobile and physical experiences.

Companies Delivering Products and Services that Begin with Digital Transaction and Conclude with a Delightful Experience

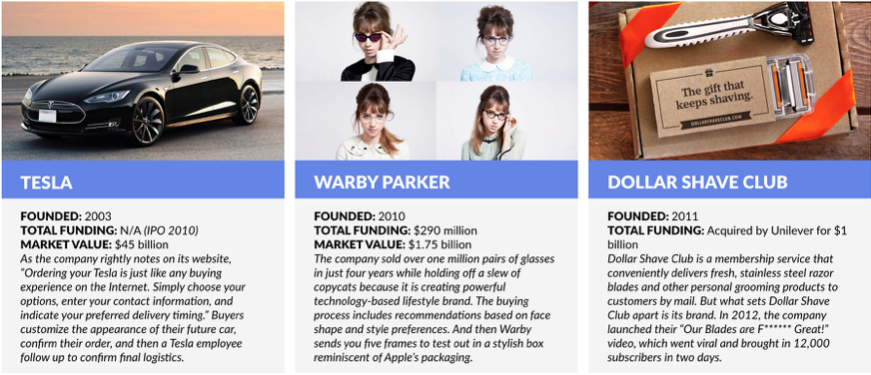

Similarly, forward-thinking retailers are unlocking the power of a delightful customer experience around the digital purchasing process itself. As Tesla notes on its website, “Ordering your Tesla is just like any buying experience on the Internet. Simply choose your options, enter your contact information, and indicate your preferred delivery timing.”

Goodbye car dealerships and awkward, high-pressure sales experiences.

The Tesla ordering process begins in a virtual “Design Studio” where buyers customize the appearance of their future car and select various options. Price changes are transparent. Once the order is confirmed, a Tesla “Experience Specialist” follows up to answer any lingering questions you may have, as well as to discuss financing options, trading in your old car, installing charging equipment, and delivery day logistics.

Warby Parker has taken a relatively expensive product — glasses — cut out the middle men (distributors and licensors), and sold it directly to consumers online at a discount to traditional retailers. For $95, you can get a cool pair of glasses, including prescription lenses and shipping. And for every pair purchased, Warby Parker donates a pair to someone in need.

But the company has sold over one million pairs of glasses in just four years while holding off a slew of copycats because it is creating powerful technology-based experience. The buying process includes recommendations based on face shape and style preferences. And then Warby sends you five frames to test out in a stylish box reminiscent of Apple’s packaging. And if you still need help deciding, you can post a picture of yourself using #warbyhometryon and the company will give you feedback. In May 2017, Warby Parker launched an app that lets users to check their prescription at home, without visiting a doctor or an optician.

From Digital to Physical

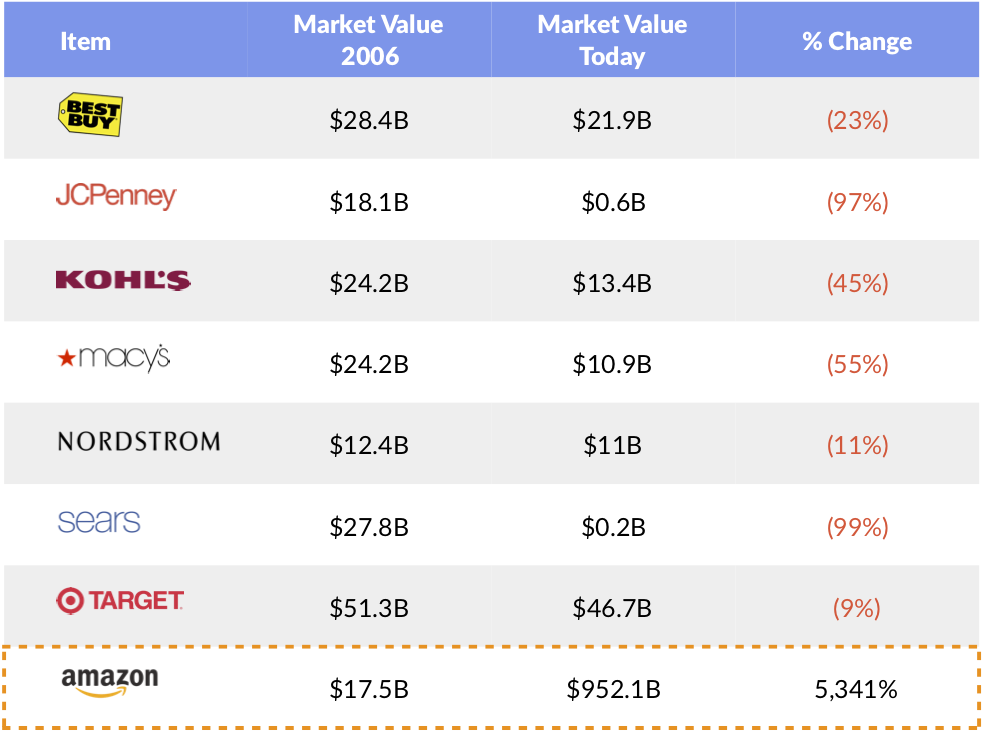

Amazon was launched in 1994 — the same year Marc Andreessen co-founded Netscape, effectively creating the Internet as we know it. Amazon started as a novel way to order books and it helped retailers like Target fulfill their fledgling online orders. At the time, Sears, once the most largest retailer in the world, had a $16 billion market value.

Today, Sears is worth $180 million and it announced that it may have to file for bankruptcy to protect itself from creditors. This week, Amazon’s market value briefly surpassed $1 trillion and currently sits at $952 billion. But it wasn’t just Sears that got steamrolled because it failed to capitalize on the digital tracks laid by companies like Netscape, and later Apple and Google.

Sears continues to struggle, closing an additional 45 stores this August, bringing the total number of stores they’ve closed in 2018 past 100. When Sears and Kmart merged in 2005, the combined company managed about 3,500 stores. Today, only 900 remain, with more closings likely. Since 2006, Sears has lost over 99% of it’s market value.

But in the Experience Economy, a new phenomenon is occurring. Paradoxically, companies that were digital first are increasingly opening physical locations.

Physical locations are an important platform to create a unique customer experience, and accordingly, brands like Warby Parker that were “born” on the Internet are turning the retail model upside-down by opening physical storefronts. Bonobos, the popular online clothing retailer that was acquired by Walmart for $310 million in May, has followed the same strategy.

Source: Warby Parker

While Warby Parker is creating a superior digital experience, the company plans to have 100 retail locations by the end of 2018, up from 70 at the beginning of the year. As co-founder and co–CEO Neil Blumenthal has observed, “I don’t think retail is dead. Mediocre retail experiences are dead.”

Not surprisingly, other companies that were “born digital” are following suit, applying the “Warby Parker” experiential commerce model to a range of consumer verticals. Casper (mattresses), Away (luggage), Glossier (beauty products), and Allbirds (sneakers), and Indochino (suits) are a few notable examples.

Launched in 2012, OZY is building the iconic media brand for the Change Generation by producing future-oriented content on unconventional and undiscovered trends, rather than stale news stories that are covered by existing outlets. The company has surged to an audience of over 40 million people per month — larger than The Economist, The New Yorker, or Politico — with original content focused on what’s new and next. (Disclosure: GSV owns shares in OZY).

Co-founder and CEO Carlos Watson, a former CNN and MSNBC commentator, argues that by engaging people with truly differentiated experiences — not simply digital content — OZY can address a premium brand vacuum in news media.

The company’s flagship event, OZY Fest, gathered over 20,000 people in New York City’s central park earlier this summer. Described as “TED meets Coachella” by the New York Times, OZY headliners ranged from Hillary Clinton to Grammy and Emmy Award-winner, Common, to Karl Rove, Chelsea Handler, and Malcom Gladwell.

As Watson sums it up, “people want real experiences.”